Sugar switch may explain link between obesity and cancer, study suggests

by Kate Wighton

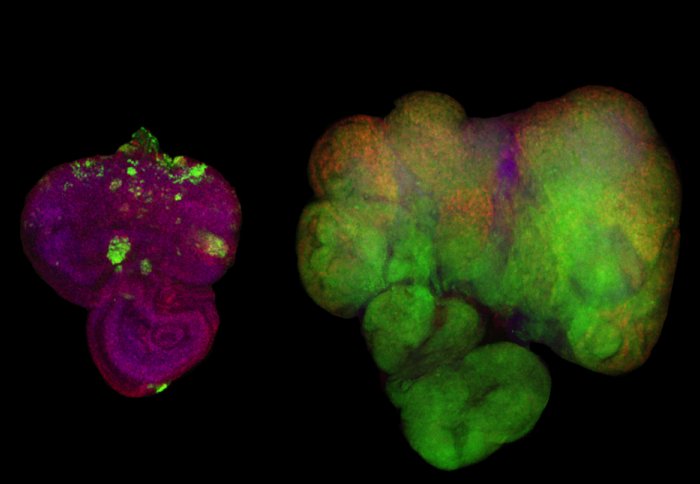

Cancer cells in flies fed a normal diet (left) vs a high-sugar diet (right)

Researchers have identified a mechanism that allows cancer cells to grow rapidly when levels of sugar in the blood rise.

This may help to explain why people who develop conditions in which they have chronically high sugar levels in their blood, such as obesity, also have an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer.

The findings were published today in the journal eLife, by Dr Susumu Hirabayashi from the MRC Clinical Sciences Centre based at Imperial College London, and Ross Cagan of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York.

When we eat food it is digested into smaller molecules, such as glucose, that pass into our blood stream. As blood is pumped around the body, it delivers glucose to the body’s cells, which use it as fuel.

For glucose to be absorbed efficiently, it teams up with a hormone called insulin. Insulin acts like a gatekeeper because it binds to receptors on the cell’s surface and triggers a ‘gate’, or channel, to open and let glucose in.

"We may be able to stop cancer cells from thriving in an insulin-resistant environment, and break the connection between obesity and cancer."

– Susumu Hirabayashi

Study author

People with obesity often have persistently high levels of glucose and insulin in the blood. Over time this fades to background noise and the body tunes out, or becomes ‘insulin resistant’. With the gate closed, glucose cannot be absorbed efficiently so it builds up in the blood and this accumulation can ultimately lead to type 2 diabetes.

But not all cells tune out. In fact, Hirabayashi and colleagues have shown in a previous study that tumour cells in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster actively tune in.

In a study published two years ago, the team engineered flies to activate the genes ‘Ras’ and ‘Src’, which are activated in a variety of cancers in people. Flies share many of the same genes that control metabolism and cell growth in people, so the findings from the study may be relevant to humans too.

The scientists activated the genes in the flies’ developing eye tissue. They also labelled these cells so that they would glow green under fluorescent light. Flies that were fed a normal diet grew small, benign tumours (above left). But when these flies were fed a high-sugar diet, they developed large, malignant tumours (above right).

Hirabayashi found that in flies fed a high-sugar diet, the ‘normal’ cells became insulin resistant, but the tumour cells didn’t. Instead, the tumour cells became more sensitive to insulin. This is because they turned on a metabolic switch that triggered them to produce extra insulin receptors. With insulin binding to many more receptors than usual, more glucose channels opened. The tumour cells became a ‘sink’ for the glucose, which had nowhere else to go in the insulin-resistant body of the fly. But this earlier study did not explain how the tumour cells turned on this metabolic switch.

Hirabayashi and Cagan studied the same flies in more detail, and in this latest study they show that the tumour cells detect glucose availability indirectly, through a protein called Salt-inducible kinase (SIK).

They found that the SIK protein acts like a sugar sensor. In response to raised glucose levels it switches on a particular growth pathway, which allows tumour cells to thrive.

“Our results suggest that if we can develop drugs to target SIK, and stop it from alerting cancer cells in this way, then we may be able to stop cancer cells from thriving in an insulin-resistant environment, and break the connection between obesity and cancer,” says Hirabayashi.

Before scientists can develop drugs to block SIK, they must first confirm that a similar mechanism happens in people.

Conditions such as obesity and cancer are too often studied in isolation, says Hirabayashi: “If researchers from these two fields of expertise were to work more closely together, each might gain useful insights from the other about possible connections.”

- Adapted from a press release by Deborah Oakley, Science Communications Officer at the MRC Clinical Sciences Centre

'Salt-inducible kinases mediate nutrient-sensing to link dietary sugar and tumorigenesis in Drosophila' by Susumu Hirabayashi and Ross Cagan, is published in the journal eLife.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Kate Wighton

Communications Division