Transforming HIV: Q&A with Professor Sarah Fidler

Professor Sarah Fidler

Since the discovery that the HIV virus was the cause of the devastating AIDS pandemic, researchers have been focused on tackling its global impact.

More than 37 million people are living with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency virus) today. Whilst AIDS carried a death sentence in the 1980s, the development of powerful antiretroviral drugs, have drastically improved the prognosis and survival rates.

Sarah Fidler is a Professor of HIV medicine at Imperial College London and an honorary Consultant Physician in HIV at St Mary’s Hospital.

Ahead of her joint inaugural lecture with Professor Alan Winston this week (29th June), Professor Fidler spoke to Tori Blakeman to explain the impact her work is having and explores the future of HIV medicine.

How has the status and treatment of HIV changed since the link with AIDS was discovered in the 1980s?

It has hugely changed. Firstly, in terms of our understanding how HIV causes disease and makes people sick, and secondly, in the development and roll out of life saving antiretroviral treatment. In 1995 treatment for HIV first became available, and now 17 million people globally are on medication. Today, people living with HIV on treatment can expect a normal life expectancy, whereas in 1985 life expectancy from an AIDS diagnosis to death was only two years.

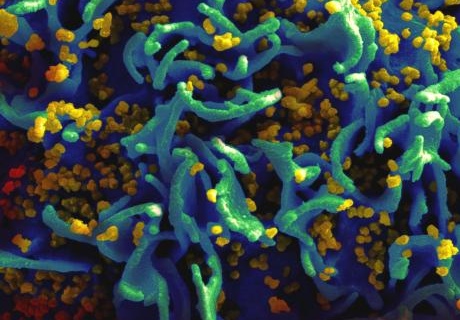

A scanning electron micrograph of HIV particles (yellow) infect a human T cell (green) - Image: NIAID

How is people's knowledge of their infection status in developing regions stopping the disease from spreading?

Using new point of care and self-testing technology, we can test ourselves for HIV, getting a result within several minutes. Point of care testing is also available in most health care settings and is being offered through community outreach programmes as well.

People who test for HIV and so know their HIV status are then able to either use known biomedical and behavioural interventions that protect them from becoming HIV-positive, whilst people living with HIV can access immediate lifesaving treatment. People living with HIV on treatment can have children without passing on the virus to them and no longer need to worry about passing the virus on to their sexual partners.

What does your research and projects like it mean for treating HIV/AIDS throughout the world?

Clinically, I look after people who have just been infected with HIV, and who chose to join clinical treatment trials, testing new approaches towards curing HIV – the ultimate goal of this research means remaining ‘well’ without needing antiretroviral treatments. There is much more research to do before this can be achieved, but there is a lot of optimism.

At the moment, although treatment for HIV is very effective, it needs to be taken forever. As soon as treatment is interrupted, the virus comes back. This is a huge burden for patients and so we need to search for something better that might allow people to safely stop treatment but remain well. To do this we need to understand where the HIV virus ‘hides’ even when people are on effective treatment, this is referred to as the ‘viral reservoirs’. Understanding where these ‘viral reservoirs’ are in the body, and why the virus comes back when therapy is stopped, will help to find a cure.

Do you think it will be possible to eradicate the disease globally?

Eradicating HIV completely is very unlikely. One man in the world has been cured of HIV, but he had a bone marrow replacement – it is highly unlikely that sort of invasive treatment could be scaled up to treat millions of people. However, it may be feasible to put HIV positive people into a remission state, that is, reducing the virus to such small levels that treatment with antiretrovirals could be safely interrupted without virus coming back. This might be a more feasible approach that could be extended one day to the global population of people living with HIV.

What part is your research playing in reaching the United Nations’ targets for tackling HIV/AIDS?

By 2020, the UN aims to meet its ‘90-90-90’ target for coverage of testing, treatment and viral suppression with therapy. This aspirational target aims to get 90% of people with HIV knowing their HIV status, with 90% of these people on treatment, and 90% of those on treatment exhibiting viral suppression.

We need to understand where the HIV virus ‘hides’ even when people are on effective treatment

– Professor Sarah Fidler

The HPTN071(PopART) trial is a community project in Zambia and South Africa, funded by the U.S. National Health Institutes and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is exploring ways of offering HIV testing on a massive scale – to over one million people in these communities where over a quarter of the population are living with HIV. The idea behind the study is that if most people living with HIV are identified and put on effective treatment, the spread of the virus to their partners and children will be greatly reduced. We are finding out whether testing and treating on this scale is possible, and if this affects the number of new infections within the community.

The HPTN071(PopART) program is helping to reach this target by training community health workers about HIV and how to do HIV tests on a finger prick sample – from which you get results straight away. Anyone who tests HIV-positive is linked into care and onto treatment. From the data we’ve collected in Zambia, 90% of the population now know their status, with 80% of these on treatment. We do not know the third as we do not measure this.

What other research into HIV do you find promising?

I think gene therapy has great potential, as this could be used to modify the cells so the virus cannot get back into cells. Also, new methods for drug delivery are looking promising, such as nanoparticles, which can get inside cells where the virus may be hiding to deliver doses of drugs.

I qualified as a doctor in 1989 and at this time young people were dying of HIV. The passion of some of those living with HIV, who I have had the privilege to look after, has driven my research career. During my research career I have seen passionate effective advocacy which has really brought about political and social change that has matched the rapid advances made in the science, and that has been inspirational. I have been very lucky.

Professor Sarah Fidler will be speaking at the special joint inaugural lecture ‘Living with HIV in 2017’, alongside Professor Alan Winston, at Imperial College on 29th June 2017. Register for your free tickets here.

Image: HIV-infected H9 T cell by the NIH National Insititute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases - CC 2.0 Flickr.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Tori Blakeman

Communications and Public Affairs

Ryan O'Hare

Communications Division