One year, two studies, two million tests

Meet the scientists behind Imperial's REACT programme

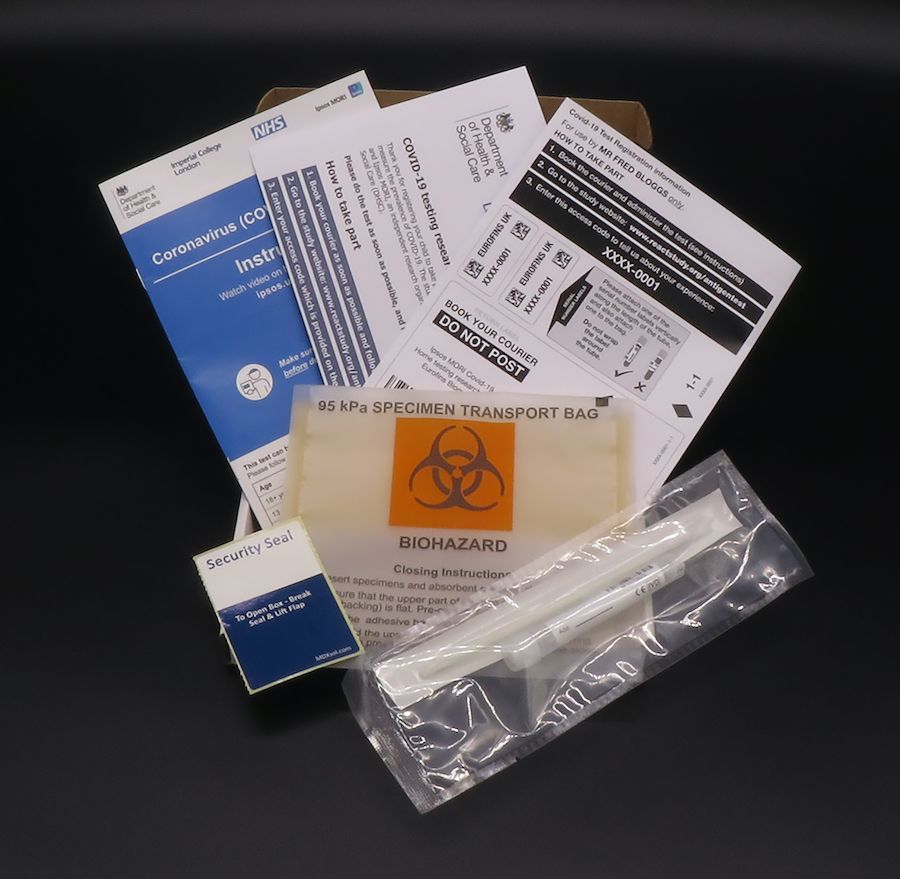

One year ago, thousands of people up and down the country began to receive a special parcel through their letterbox.

These packages contained a testing kit which would ultimately reveal whether they were infected with a novel virus that was wreaking havoc across the globe.

These individuals were the first of 120,000 volunteers to carry out a home coronavirus test that month, as part of what would become one of the world’s biggest studies of community COVID-19 testing, REACT.

The two arms of this programme, REACT 1 and REACT 2, have been tracking infections past and present ever since. Led by a team of Imperial College London scientists, more than two million people have taken part in REACT to date. This colossal effort has gleaned insights that would offer a novel lens on the virus and shape the country’s response to the epidemic.

We meet the scientists behind the programme who tell their stories of how it all unfolded, what they’ve learned, and their hopes for REACT’s legacy on science and beyond.

Professor Ara Darzi

Sponsor of the REACT programme and co-director of Imperial’s Institute of Global Health Innovation

“Last April, in the middle of the first lockdown, we pulled together a multi-disciplinary group of experts from across Imperial to form what would become one of the country's largest COVID-19 surveillance studies.

"Everyone had a unique skill to offer. There was Paul Elliott, an epidemiologist; Steven Riley, a disease modeller; Graham Cooke, an infectious disease specialist; Wendy Barclay, a fantastic virologist; and Helen Ward, a public health and public engagement expert.

"I hadn’t worked with any of these researchers before. There was a lot of chemistry to be developed in the team.

“What we wanted to find out was how much of England’s population had already been infected with this new virus.

"At the time no one knew.

"A type of finger-prick test called a Lateral Flow Test had been developed to detect antibodies to the virus, and had been proposed as a way to track people's exposure to it.

Having a simple test people can perform at home, at scale, to tell them whether they’d already had the virus would have been a fantastic tool.

But we didn’t know whether these Lateral Flow Tests would be the answer.

“We also really needed to know, at a much more granular level, who had the virus at any one time. So that was our negotiating position, and we ended up agreeing to launch both of these major studies – to find out the prevalence of current and past infections.

“It was a huge exercise getting them off the ground, which wouldn’t have been possible without our partners, Ipsos MORI, and the tremendous help from our funders, the Department of Health and Social Care.

"Initially we were only contracted to run the study for one round. It’s now been going for a year and has been extended again. And that’s because of the amazing impact it has had.

"REACT has contributed hugely to the scientific knowledge base of the country’s epidemic and has influenced many government decisions in terms of the interventions they’ve taken, and when.

“And what still astounds me is the scale of the programme. The millions of people across the country who have received a letter inviting them to take part. Including myself! It was a bit of a surprise to receive a letter, from me, asking me to join REACT.

“I’m just delighted that we came together and did it. I’m so proud of the team.”

Professor Paul Elliott

Director of the programme and Chair in Epidemiology and Public Health Medicine

“Back when we were launching REACT, we had no idea what was going on in the population. To really find this out, you can’t only rely on who comes into hospital, goes to their doctor or sadly dies.

This is the tip of the iceberg.

"At the time, everything else that was happening – the big hidden bit under the sea – wasn’t being measured. Testing was very limited.

"So that’s exactly what we’ve been doing since last May, and is what gives REACT and ONS their great strengths – the fact that they are community-based and offering real insights at the population level.

“We’ve been able to describe the epidemic as it’s unfolded in England, since the end of the first wave...

...offering a complete picture of its behaviour.

Our data has ended up being an early warning of what’s coming.

We were one of the first to pick up rising infections back in September, the beginnings of the second wave.

REACT data showing how coronavirus prevalence has changed over the past year (dotted line in December represents estimates as no data were collected during this period)

REACT data showing how coronavirus prevalence has changed over the past year (dotted line in December represents estimates as no data were collected during this period)

“REACT has also taught us a lot about the virus. All the time we’re finding out more about where it transmits, how, and who it spreads to.

"We’ve also learnt about the effectiveness of public health interventions. Lockdowns are a blunderbuss approach that impact people’s lives and society more widely in many ways. But they do control the virus. Each time the country has gone into lockdown, our data has shown that it’s brought the epidemic under control. And when you can bring virus levels right down, there is the opportunity to open up society again in a cautious way.

This is what has also allowed the vaccine programme, which has been incredibly successful so far, to take hold.

“Going into this programme, we knew we were doing something important. We didn’t really have time to think about whether it was going to be influential. But we knew that we had to do it well.

“Establishing the REACT programme, funded by the Department of Health and Social Care, has enabled us to develop our research further into COVID-19. We're hugely grateful to the additional support we've received from NIHR, UKRI, HDR UK and the Huo Family Foundation.”

Professor Steven Riley

Professor of Infectious Disease Dynamics

“When we started the programme, infections were falling in England. I was really enthusiastic to join the study and I wanted us to generate evidence that would be useful for the start of a second wave. We were certain it was going to happen, but we didn’t know when or how big it would be.

“And I think one of the most significant questions we’ve answered as a team is: how best can we generate a reliable picture of what’s happening? Using data from people who put themselves forward for testing won’t give you this, because it’s biased. To get the most current information possible, we knew we had to get a completely random sample of the population, so that’s what we did.

“Because infections were coming down at the start of the study, we also needed to work out the minimum number of samples we needed to be able to detect small numbers of infections. So we’ve been swab testing about 150,000 people every month, randomly selected from every Lower Tier Local Tier Authority in England, which gives us the power to pick up early changes.

“It was this simple but effective design that enabled us to detect subtle regional patterns in November and December that we later found out were the beginnings of the Kent variant wave taking off.

"What we saw was that even in lockdown, infections were starting to grow again but not in a uniform way, rising in Kent, Essex and east of London. We didn’t know why this was happening at the time, but we could clearly show something was going on and report it.

“People’s enthusiasm and interest for what we do has really taken me by surprise. We’ve done a lot of media interviews; they’re fun, but also stressful. The highlight was definitely going on Adrian Chiles’ show on 5 live. His first question was along the lines of: “Tell us how you do this, I love this study and how it works!” He’s a bit of a hero of mine, and it surprised me that people seemed to immediately get it and see the value of REACT.

"I thought it would be useful and interesting to policymakers, but I didn’t think that the public would appreciate it in the way that they have.

“It’s really gratifying to know that the work has been useful to both decision-makers and the public. As a public health scientist, you can’t ask for much more.”

Prof Helen Ward

Professor of Public Health and Director of the Patient Experience Research Centre

“I’ve spent 30 years doing infectious disease control and research, so the pandemic was an obvious focus for my research. I had previous experience of community testing programmes, which I used to help design the REACT study.

"Although the finger-prick antibody tests had a bad reputation when we started out, I knew that it was possible to use imperfect tests to gain valid research insights.

“A key factor in implementing successful new technologies or research programmes is ensuring that the users are engaged in the design. For a home testing programme, this meant involving members of the public early on to get advice on how best to develop the project, what kind of instructions would be needed, and so on. After all, they are the audience we were aiming to reach, so we made sure to embed public involvement throughout REACT right from the start.

“Very early on we held an online focus group on people’s attitudes towards finger-prick testing, and from there we recruited a public advisory panel that continues to meet regularly.

They have added so much to the study, helping us design the materials that we send out to participants, and improving the way that we interpret the results so that they’re clearer and easier to understand.

They also constantly remind us about the importance of making this study accessible to people who are often excluded from research....

...and people from different backgrounds and ethnicities.

“Because we have reached a diverse range of people, we’ve been able to show that there are inequalities in exposure to the virus, and also the fact that this is so closely linked to structural factors such as employment, housing, ethnicity and family size. I think these are some of our most important findings.

“This has definitely been some of the most interesting research I’ve ever done. While it’s also been the most intense! It’s been so rewarding because you can see that you are making an impact and gaining new knowledge that people are waiting for. Often with research it’s the other way around – you’re trying to get people interested in what you’ve found.

“I do think this study is unique globally and has lessons for how we respond to future epidemics and other kinds of health challenges. I think that will leave a lasting legacy.”

Professor Graham Cooke

NIHR Professor of Infectious Diseases

“As the impact of the first wave of infection was in beginning to wane, it was clear we needed to better understand where the virus was at a given moment, but also where it had been and how it had impacted different parts of the population. We needed a way of assessing that, and we managed to pull together a method to do this in a ludicrously short period of time.

What in normal academic times would probably take a year was done in a few days.

"There were some very long nights, but we managed to get in the field and start testing within about a week. It shows you that you can do things when motivated (and funded, of course).

“When we started, we didn’t have any experience of using these tests in a home setting. We were more comfortable with the swab testing side of REACT, as home swabbing had been done in other settings. But home antibody testing at this kind of scale, as a nationwide surveillance study, hadn’t been done before.

“One of the key parts of REACT that enabled us to launch this antibody survey was the early studies we carried out in the lab and with members of the public and NHS staff. These gave us a good understanding of how the tests worked, how good they were, and how well people could use them.

By going through these critical steps in a quick and rigorous way...

...we were able to scale up with confidence.

“Doing something so large and immediately relevant has been very rewarding. Now over two million people have participated in REACT; people who want to do it for a mix of altruistic reasons and to better understand their own health needs. The level of engagement has surprised us all.

Volunteers weren’t paid for taking part, so it shows people understand the importance of participating in research, which is vital for making progress in science.

“Into the future, I hope this leaves a positive legacy for research engagement, as more people can see the contributions they’re making to science. There is also a great opportunity to learn more about the biology of disease that we are only just beginning to do within REACT, for example understanding better the causes of Long COVID.

“One of the most rewarding aspects of working on the project has been its genuinely multidisciplinary approach. Whenever there has been a problem, there has always been someone in the group with a specific skill that can solve it – like a scientific Swiss army knife.

"The whole thing wouldn’t work without any one of them.”

Professor Wendy Barclay

Action Medical Research Chair of Virology

“Sometimes I still think: What on earth am I doing here? I’m a molecular virologist who works in a lab, I don’t normally do big studies on huge numbers of people! But I’ve found my way.

“I was already part of a group that was exploring what was needed in terms of tests for large-scale antibody surveys. I’d never used these Lateral Flow Tests before, so I was curious and wanted to know whether they were any good. So we started evaluating these finger-prick tests in the lab to find out how accurate they were and whether we could trust them. I was pleasantly surprised when we found a couple that were actually really good.

“Having persuaded myself that some of these kits were accurate enough, we then had to ask: what can you learn when you send them out to the community? Not only who has antibodies or not, but are these antibodies lasting? We wanted to know whether these tests could detect evidence of waning antibodies in the population, and they did.

This is a controversial subject, because we still don’t fully understand what this means and whether it’s linked with waning immunity.

Now we’re starting to ask and answer new questions with these tests.

How have the different vaccines impacted the population’s antibody profile? It’s really exciting to see the data coming through.

"In our most recent round of testing, we could see that people were developing antibodies after receiving the vaccine, and we could spot differences across different age groups and after the second dose. It’s gratifying because it shows you’re measuring something meaningful in the community.

“What’s amazing to me is the power of numbers. Most of the work we do in lab is with very small numbers of animals or cells, so everything has got to work. But in big community studies it doesn’t matter if a few people don’t prick their fingers quite right, because when hundreds of thousands of people are doing it, it all comes out in the numbers.

“I think my biggest learning has been that science in the real world is so important. It’s opened my eyes again to a whole bunch of science that I’m not normally involved with.

And I think that there are things we’ve learned from REACT that will feed into the future with how the world deals with the next pandemic.”