Key protein boosts cellular ‘recycling’ system to protect against herpes virus

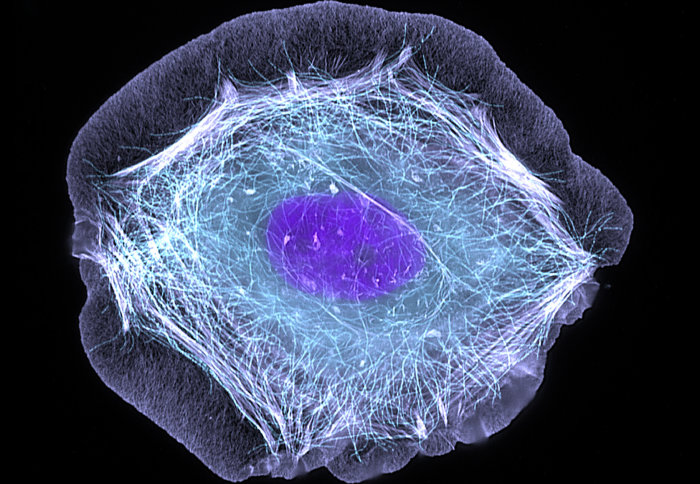

Researchers used skin cells to investigate the role of autophagy in protecting cells against the herpes virus

Research reveals that the TBK1 protein is key to maintaining cell viability during infection.

A new study has shown that autophagy – the natural process by which cellular waste is disposed of and recycled – plays an important protective role in fighting herpes infection in the body. Specifically, the findings, published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, demonstrate that the protein TBK1 is essential in triggering autophagy, thereby reducing infection-induced cell death in the face of the virus.

The Imperial team behind the study previously demonstrated that the production of interferons – proteins that are made and released by cells as an anti-viral response – was important in herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) immunity. However, their latest research identifies for the first time how autophagy lends a second helping hand in protecting cells against the virus.

Significantly, the findings point to new possible treatment options for herpes encephalitis (HSE), a rare but often devastating condition in which the herpes virus enters the brain. In its early stages, HSE is often difficult to diagnose due to the general, flu-like nature of its symptoms. However, as the infection progresses, the virus causes significant inflammation in the brain, which can result in seizures, changes in personality and behaviour, and the progressive impairment of brain function. Following treatment, patients will often be left with permanent neurological damage.

A chink in the armour

To investigate the role of autophagy in HSV-1 infection, the team collected dermal fibroblasts – skin cells that generate connective tissue and promote recovery from injury – from healthy subjects, as well as HSE patients deficient in TBK1. In the lab, the researchers then infected the samples with HSV-1 in order to compare if and when autophagy took place across the two groups.

In the healthy control group, the infected skin samples showed a clear increase in autophagy markers, indicating that the cells’ protective mechanisms had been put into full effect in response to the virus. However, in the TBK1-deficient group, there were no changes in autophagy markers, suggesting that the cells’ immune response to the virus was impaired.

Using immunofluorescence imaging, the researchers found that when infected with HSV-1, two different kinds of autophagy were triggered in the skin cells of the control group at different times during the course of infection. However, the team observed that the earliest stage of autophagy did not occur in those with TBK1 deficiency. Furthermore, when the protein was inhibited in the control group, the team saw similar results. These findings indicate the importance of TBK1 in triggering autophagy during the first stages of infection, which is in turn crucial to ensuring the effective survival of cells.

Implications and next steps

“Increasing cell viability after infection is critical, and autophagy appears to play a key role in this respect,” explains Dr Vanessa Sancho-Shimizu, who led the study.

“The fact that autophagy is important in reducing cell mortality upon infection is important, as this provides us with another way to combat HSV-1 infection. It may also help in reducing excessive inflammation, which is a consequence of infection and may contribute to the neurological sequelae suffered by most HSE patients.”

The team are now keen to build on their findings by repeating the study with cells from the central nervous system using a larger cohort of HSE patients.

‘Human TANK-binding kinase 1 is required for early autophagy induction upon herpes simplex virus 1 infection’ by Liyana Ahmad et al. is published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Image credit: Torsten Wittmann / ZEISS Microscopy, Flickr.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ms Genevieve Timmins

Academic Services