Bringing different perspectives: navigating education and career with a disability

Dr Patrick Dunne

Future Leader Fellow (Advanced Research Fellow)

Department of Physics

International collaboration

I came to imperial to start a PhD in particle physics in 2012, working on the Large Hadron Collider. After finishing that I was lucky enough to stay at Imperial and start a postdoc in neutrino physics. My research involved sending a beam of subatomic particles called neutrinos, and their antimatter equivalents, from one side of Japan to the other and watching how they change during the journey. Their behaviour could hold the key to why our universe is made of matter, not antimatter.

A UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship is now allowing me to build a team to continue this research. I’m also going to be working on another neutrino experiment in America called DUNE (Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment). So my career has been based at Imperial, but working on these big international projects.

Positives and negatives

I think I was about seven when I had the full diagnosis for Asperger's and dyspraxia, and then at around eighteen the Tourrette’s started. Tourette’s for me manifests in muscle twitches and vocalizations that I can suppress with quite a lot of effort, but that makes me tired and stressed, and leads to muscle pain issues.

It was particularly bad during the pandemic when we were all pushed on to virtual meetings, because one of the things I find stressful is talking to people when I can't quite read how they're reacting to me. I'm not as good at reading social cues anyway, and in virtual meetings it’s even harder. On the other hand though, I found that some people started to tell me, “I now understand how you must feel normally, because I'm finding it harder to pick up on things.”

That's the downside of it all. But on the plus side, I can focus on things for a long time, and I love really getting down into the details of a problem. And people have given me positive feedback on my presentations – I’ve heard that people with dyspraxia can often be good at storytelling.

Early diagnosis

I was very lucky to have been diagnosed pretty early, so I grew up with help and coping strategies, and I’ve been able to learn the behaviours that come to other people automatically. I'm really bad at making eye contact, but I was taught when I was very young that if I just stare at the bridge of people's noses, that works fine.

Speaking up

Particularly with hidden disabilities, people will often assume you don't need any help, so it’s important to speak up. If I’ve been at a conference with a lot of social interaction and then a long flight home, I will have got really stressed and my muscles will be really painful. When I’ve mentioned it to my line manager, he’s been absolutely fine with me taking a day off to recover and get back into a state where I can be productive again.

Neurodiversity can bring new perspectives

I had some bad experiences with bullying when I was a child, but I’ve found that science is a place that's really helped me get away from that. It’s an area where bringing new perspectives is encouraged, and I think the innovation that people with neurodiversity can bring is something we should really cherish. I'm very glad I've had the opportunity to come into this community and work with people from around the world to do amazing things that none of us could have achieved on our own.

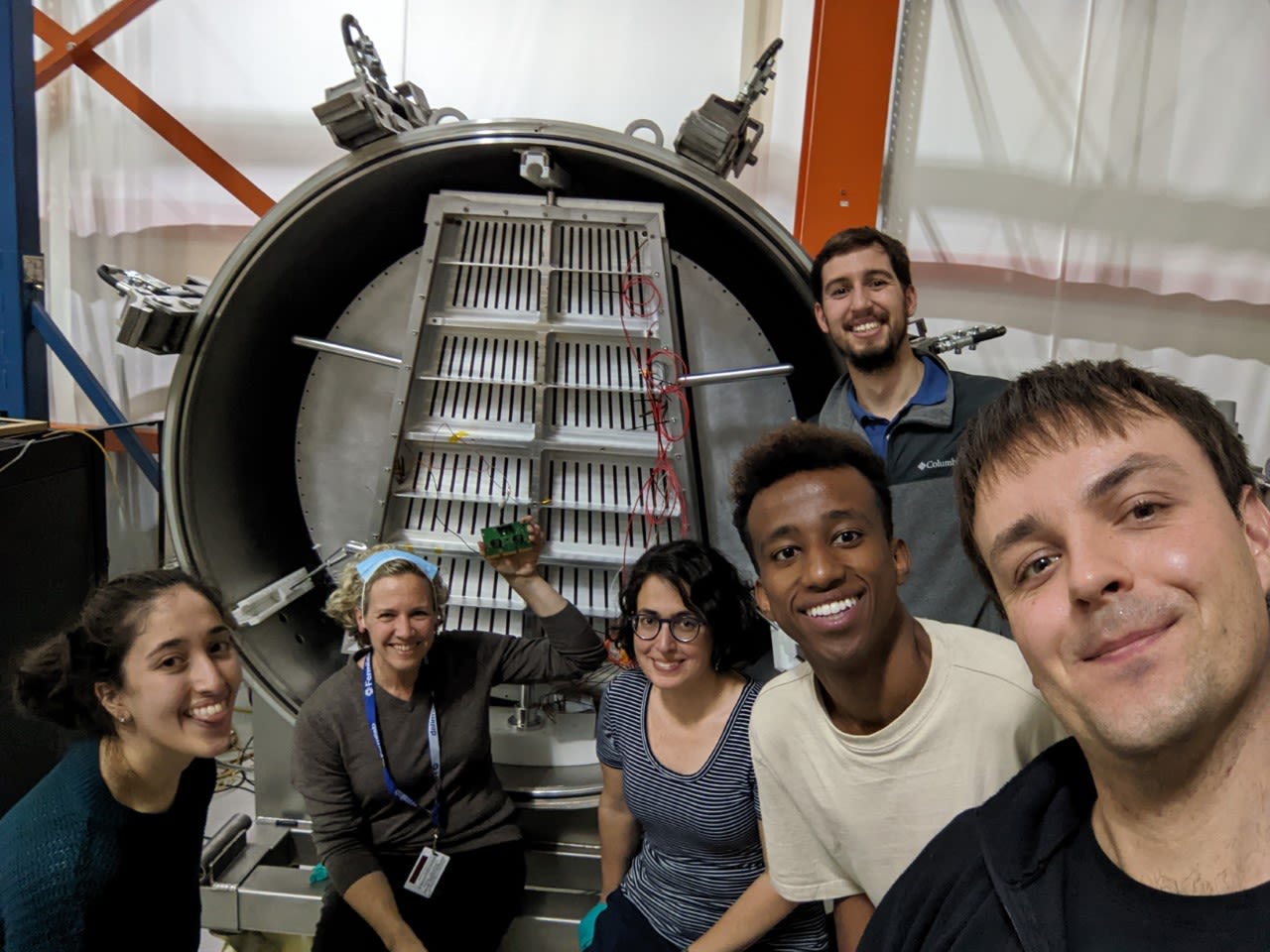

Patrick and team in front of a prototype neutrino detector (part of the DUNE project)

Patrick and team in front of a prototype neutrino detector (part of the DUNE project)

Projects that Patrick has worked on have featured in Nature

Projects that Patrick has worked on have featured in Nature

Jasmine Chan

Undergraduate

Department of Chemistry

Art and science

My interest in Chemistry was sparked by something seemingly simple: a flame test. I was fascinated by the array of bright colours. After further studies, I became captivated by the theory behind all sorts of phenomena happening around us in our daily life. Chemistry can provide the answer to my questions. My current aspiration for my career is to become a cosmetics chemist, as it bridges my passion for makeup artistry and science.

Looking to the future

Discussing my future career plans with my course mates and personal tutor has been most helpful in navigating my career plans. As many around me are very determined and career-driven, it has been motivating to push myself towards getting my dream job. There are also Imperial careers events and various societies where I have been exposed to potential careers that I had never considered before.

Inspiration

I would like to spotlight my science teachers from my secondary school, who continuously pushed me to stretch myself academically. Having these role models, who love their job and have a strong passion for science, was inspiring throughout my teenage years. They are the reason why I am pursuing science at a higher level.

A famous scientific figure that inspires me is Marie Curie. Her absolute determination to succeed is astounding - as seen by her incredible discoveries such as radium and polonium. And this was whilst being a woman in STEM at a time when women were oppressed. Marie Curie inspires me to continue pushing and not give up as a woman in this field.

Representing disabled students

I am diagnosed with fibromyalgia, a hidden chronic pain disability. It is a long-term condition that makes me always feel widespread pain and muscle stiffness around my body, and there is no cure for it. My diagnosis correlates to my stress levels, where the symptoms heighten when I am more anxious. Despite the lack of treatment, some medications can ease some symptoms.

I am currently working part-time for Imperial College Union as their Disabilities Officer. This role allows me to represent the disabled student body at Imperial. Since starting in August, I have been heavily involved with the Disability Advisory Service, staff members and other union officers, which has allowed me to feel integrated within Imperial’s community. My current aim is to unite the disabled student body of Imperial, and I have thoroughly enjoyed meeting other students in this community. I have also had the pleasure of being surrounded by wonderful Liberation and Community Officers and Officer Trustees. Seeing everyone’s goals and aims to change the university in a positive direction has been inspiring.

Dr Ad Spiers

Lecturer in Robotics and Machine Learning

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering

Cybernetics, robots, and the jungle

After I’d finished my bachelor’s degree in cybernetics at the University of Reading, I was hired to be a research assistant while doing my Master’s. It was quite an intense experience, so after that I spent a year backpacking in South America. I was so sick of computers and technology that I lived in the jungle without electricity for six weeks!

On returning to the UK, I worked for a while in the nuclear industry with robots, followed by a PhD and postdoc at the University of Bristol. I then did another postdoc and research work at Yale University, and then I was at the Max Planck Institute in Germany for several years before coming to Imperial.

Invisible disabilities

I have a few mental health disabilities and have yet to receive a comprehensive diagnosis, even though I'm now 40! One of the things I suffer with is obsessive compulsive disorder. I have quite a rare form called autogenous obsessive compulsive disorder, which basically means I have intrusive, repetitive thoughts about very minor things that won't go away. These thoughts can dominate my cognitive spectrum, making it very hard to focus on work.

I also suffer from psychosis, so I have frequent hallucinations – visual, auditory, and previously tactile as well. They used to be a lot more disturbing, and quite frightening, but now I've come to live with them. Still, trying to hold it together in meetings is really challenging when you can see things in the room that you know are not there.

And I’ve suffered from depression for a long time. I think the emotional roller coaster of doing a PhD, which everyone struggles with, felt like it was amplified by my depression and other conditions.

Challenges

I didn't receive a diagnosis for my psychosis or OCD until I was about 34. I’d been to doctors before, but they kind of dismissed me. I think one of the difficulties with mental health that always shocks me is just how difficult and bureaucratic the process can be. The first time I went to a doctor and said, “Help me – I keep seeing things that aren't there”, the doctor's response was “that sounds like fun”, and then they sent me away. Another time I was told that I couldn’t possibly have mental health conditions because I lecture and stand up in front of people. I spent most of my career thinking there was something wrong with me, but I didn't know what it was, and I couldn't get any support.

A lot of the environments I've worked in were really competitive, which was hard to manage. In one of my labs it was considered absolutely normal to leave work at 4am and start the next day at 10am. Any excuses for why you weren't able to work late, or why you weren't producing as many papers, just wouldn't have gone down very well.

How to cope

I don't know what I would do without the support that my wife has given me, especially during the various times when neither of us has really understood what was going on with my psychosis or OCD.

In the US I was able to find a good psychiatrist and we went through a number of different medications until we found a combination that worked. I know many people are against medication, and I completely understand why. But without it, I don't think I would have a lecturer job – I don't think I would be able to have any technical job, to be honest. It's really been life changing. The medications even mostly stopped some movement issues I had had for years.

In the past I tried to keep my mental health conditions a secret, due to a lack of understanding where I’ve worked. But being open about it in the last few years has really helped. And it's helped a few of my students, who have then opened up to me about difficulties they have been experiencing.

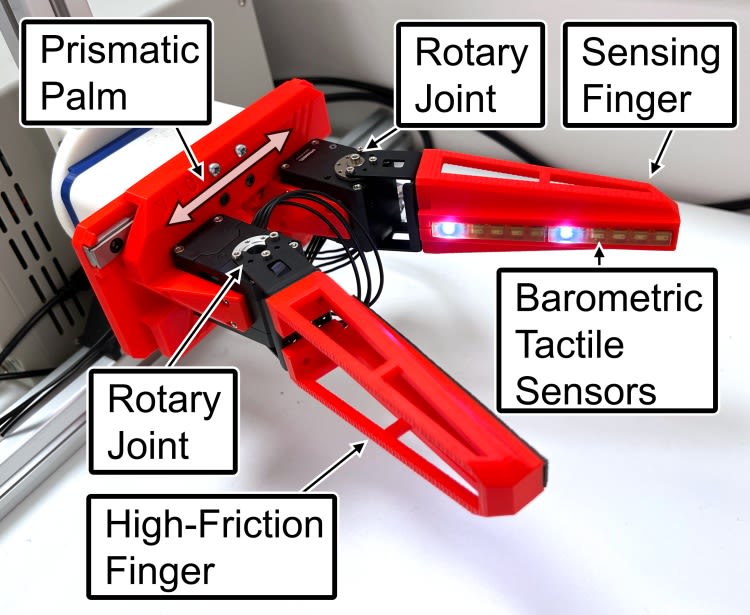

The E-TRoll robot gripper built by Ad and his team

The E-TRoll robot gripper built by Ad and his team

Ad with his wife Dr Nav Sagoo

Ad with his wife Dr Nav Sagoo

Caroline Gilchrist

Student Wellbeing Adviser

Department of Computing

Caroline with her bandmates

Caroline with her bandmates

Finding the right path

I did my first undergraduate degree in English literature, a subject I knew I liked and thought I was good at. I hadn't really given much consideration to what I would do with it afterwards, so when I first graduated, I felt I was in a bit of limbo because I really didn't know what to do next.

In the end I did a TEFL course and I went abroad to Spain. It was only supposed to be for a year or so, but I ended up staying for 15 years. I started out working in a private language school, then went on to run my own school, and a translation service. Then for the last few years I worked within the state school system on a project to promote bilingual education, while also doing an MA in Linguistics.

On returning to the UK, I worked at the University of London teaching a bit of linguistics, but mainly English and study skills to international students. I was also a personal tutor and had to provide a lot of support, and it was this pastoral care aspect that I found the most rewarding. So I decided to try and transition to the advice and wellbeing sector within higher education, which is where I am now. I'm also currently doing an MSc in mental health and wellbeing psychology.

I love working with students. I think going to university at whatever level can be the most exhilarating and yet also the most daunting experience you can have. People have always fascinated me and I get to meet and support a really diverse student body. I think one of the biggest challenges is getting people to talk more openly about mental health - I think we’d all do a lot better if we could have more of those conversations.

Perceptions of disabilities

I have a condition called albinism which means that I have no melanin which provides pigmentation for skin, hair and eyes and so on. It means that I'm very sensitive to the sun but, more significantly, melanin is very important in the formation of the optic nerve in utero. This means I am visually impaired and my eyes are also very light sensitive because my retinas don't absorb light.

I think I'm very aware of my own capabilities and limitations but trying to put that across to other people is sometimes really difficult. Sometimes people grossly overestimate or underestimate what they think I can do. It can also be challenging to deal with other people's perceptions and attitudes. I've been to job interviews where when my disability has come up, the tone has completely changed, and I just want to end the interview and leave.

Thinking outside the box

What has been a great help to me in my career is having friends that I could talk to and who have been able to offer practical advice. For example, when I wanted to move from teaching to the more pastoral side, I really didn't know how to do that. I knew I wasn't able to afford to go back to university and retrain at that time, so I had to find another way. And I was lucky enough to have some savvy friends to help.

I’d say to other people with disabilities: try to think outside the box. There's more than one pathway into a lot of careers and if you're willing to explore other options, and commit some time to it, then it is possible to find different avenues like I did. The other thing is the importance of persevering. If you know you're capable of something, then don't let anyone tell you otherwise.