STRONGER, TOGETHER

IMPERIAL HAS ASSEMBLED THE LARGEST CRITICAL MASS OF EXPERTS IN THE WORLD TO TACKLE THE LEADING THREATS TO GLOBAL HEALTH.

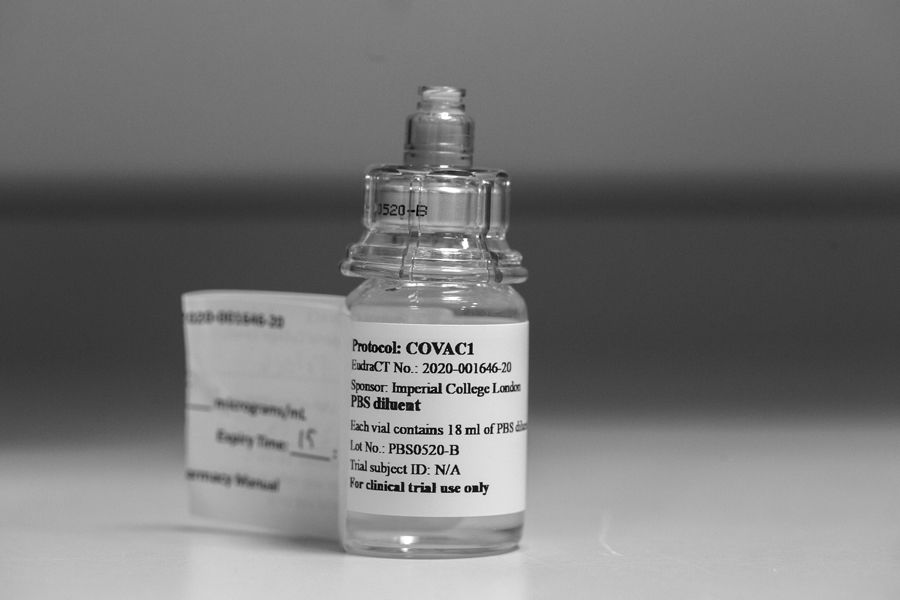

For Imperial’s researchers, it all started around 40 years ago with HIV. Then came Hepatitis C. Ebola. SARS. Preparation for what the WHO was calling ‘Disease X’. And then COVID-19 arrived – and those same researchers were ready to put their experience, knowledge and expertise to immediate use.

But it doesn’t stop there. Imperial has just launched the Institute of Infection, bringing together those decades of experience and everything that has been learnt over the past two years with a simple goal: to assemble the largest critical mass of experts in the world, ready to tackle everything from malaria and HIV to antimicrobial resistance and the next pandemic.

The unique juxtaposition within the College of clinical medicine, biomedical science, engineering and natural sciences is what gives Imperial such strength, says Professor Charles Bangham, Co-Director of the Institute. “We have had all of that for a long time. The question is whether we exploited the potential to the full, and the answer to that in the past has been ‘no’. The opportunities for closer collaboration have been obvious for a long time. And the final go-ahead couldn’t have been more timely – just before the start of the pandemic.”

“We have no idea which virus will emerge next... We must exploit Imperial’s interdisciplinarity, not only to get answers but to identify the problems ahead.”

A professor of immunology whose research focuses on the human T-cell leukaemia virus, Bangham finds it helpful to interact with academics across multiple fields, from physics and mathematical modelling to virology and anthropology. “My interests are necessarily wide. I talk to anthropologists and zoologists, for example, because emerging infections nearly always come from contact with animals and other cultural practices. The pandemic has brought our vulnerability into focus. We have no idea which virus will emerge next, nor do we have any idea to even a few orders of magnitude how many viruses exist globally. We must exploit Imperial’s interdisciplinarity, not only to get answers but to identify the problems ahead.”

Professor Charles Bangham, Co-Director of the Institute of Infection

Professor Charles Bangham, Co-Director of the Institute of Infection

Professor Wendy Barclay, Head of the Department of Infectious Disease in the Faculty of Medicine, says the last two years of the pandemic opened her eyes to the wealth of knowledge in the field of infection at Imperial.

“COVID has been an incredible journey for me – an overwhelming one at times. I have had to do a lot more in terms of advising on policy than I expected. It took this time of crisis to make me realise the huge benefits of interdisciplinary research. I was drawn into the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), where all different views of the pandemic were on the table, from the behavioural biologists to the modellers and ethicists. It made me realise how vital it is to study infection in the round.”

In her role as lead of the G2P-UK National Virology Consortium, Barclay was instrumental in bringing together leading virologists

from ten UK research institutions, boosting the UK’s capacity to study newly identified virus variants . Their virological insights are combined with those from many other disciplines to rapidly inform government policy.

“It might have taken a pandemic, but we have shown ourselves very capable of working across academic boundaries.”

Through the REACT study, Barclay and her team have been working closely with academics from public health for the first time, and she has also found herself talking to engineers developing diagnostic tools and understanding aerosols, as well as medics running trials in the hospitals.

“Historically, there was no pathway at Imperial for those working on the many aspects of infection to make the right connections. They happened, of course, but it tended to be piecemeal. It might have taken a pandemic, but we have shown ourselves very capable of working across academic boundaries. Ideas that we were already formulating have crystallised, and this cross-disciplinary approach paves the way for the success of the Institute. It is crucial that we maintain this new-found impetus around infectious disease.”

Professor Wendy Barclay, Head of the Department of Infectious Disease and Action Medical Research Chair of Virology

Professor Wendy Barclay, Head of the Department of Infectious Disease and Action Medical Research Chair of Virology

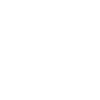

Professor Robin Shattock, Chair in Mucosal Infection and Immunity, has spent the last 30 years working on developing a vaccine against the HIV virus. “There is still a long way to go, but we are inching closer. Before the pandemic, there were no RNA vaccines, and the crisis proved a tipping point for technology. The SARS- CoV-2 vaccines have been a huge success, but this is a relatively easy virus to deal with. Within a single HIV positive individual, you can find more variants than exist globally for COVID.”

Shattock is confident that the Institute will accelerate critical research. “COVID has put pandemics higher on the priority list for governments around the world, but that has not necessarily yet translated into the backing or funding required to make things happen. The multidisciplinary approach of the Institute will allow us to make new, focused connections so that we can coalesce around key scientific problems that cannot be solved by one individual.”

He points to the increasing threat from antimicrobial resistant bacteria, and says vaccines could have a role to play here. “To understand the challenge, I need to talk to people beyond the inner circle of infection – to natural scientists and chemical engineers, for example, who understand the vaccine formulation and have the manufacturing experience. Any product we develop needs to be scalable for real-world use, not just an academic exercise.”

“I believe that we can make malaria history – and for that we need an effective vaccine”

Professor Faith Osier, Executive Director of the Human Immunology Laboratory at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and a specialist in malaria, has recently been appointed Co-Director of the Institute alongside Charles Bangham. She has great hopes that, by bringing together disciplines who in the past would not naturally have talked to each other, answers will finally be found for problems that have existed for a long time.

“I believe that we can make malaria history – and for that we need an effective vaccine,” says Osier. “The only malaria vaccine that has been approved by the World Health Organization provides around 30 to 40 per cent protection, whereas for the COVID vaccines we have achieved around 90 per cent. We know there are people in Africa who have become completely immune to malaria after repeated infections. Antibodies have been shown to be critically important but, because our bodies make billions of different antibodies, it has been difficult to pin down the ones that actually eliminate the parasites. Human challenge studies are helping us to address some of these questions. They involve different teams of scientists from a wide range of disciplines, and the Institute will provide exactly the type of collaboration that is needed.

“Good health infrastructures in Western countries have protected the population from experiencing the profound negative outcomes that can arise following infection,” continues Osier.

“The pandemic has brought this home and reminded us all why we should care about global public health. The positive impacts of COVID vaccines have made it much easier for me to explain why we must develop highly effective vaccines for malaria and other infectious diseases. The Institute of Infection harnesses the power of collaboration and gives me the chance to turn my dreams, and those of others, into reality.”

Professor Faith Osier, Co-Director of the Institute of Infection

Professor Faith Osier, Co-Director of the Institute of Infection

Echoing his Co-Director, Charles Bangham is also excited for the future of the Institute. “It has been remarkable how universal the support for the Institute has been. The experience of the pandemic has made people realise how much we need it. Imperial has become very well-recognised as a source of knowledge about infection, both among policy makers and the general public. The Institute allows us to present a co-ordinated face to the outside world.”

And as Proconsul and Professor of Experimental Medicine, Peter Openshaw is relieved to see the long-term plans finally come to fruition.

“There are so many brilliant academics working here across infectious disease, but sometimes it has felt easier to collaborate with California or Hong Kong than colleagues in the next-door lab. Twenty years ago, we had a vision for a centre on the St Mary’s Campus to encourage collaboration. It has taken a while, but now finally we have an Institute that is so much more than just one building, bringing together all that Imperial has to offer in terms of the science and research around infection.”

A regular on the airwaves since the early days of the pandemic, Openshaw remains convinced that, as people doing studies paid for from the public purse, Imperial researchers’ mission of education is much broader than just to their students.

“The communication of science is absolutely central to what we do. It has been rewarding for me to see politicians picking up phrases and explanations scientists have used on the radio or television and then quoting them in Parliament. By engaging with the media, we can get our message across to many audiences.”

“You prepare for war in peacetime, hoping it will not happen. We must continue to plan for the next pandemic even as we go through this one”

It is a message that Openshaw and his colleagues hope the new Institute will keep in the public eye. “I was involved in many studies of the 2009 influenza pandemic, and since then investment in additional studies of respiratory infections was hard to sustain.

“The COVID pandemic has again put infection centre stage, but we must beware of slipping back into complacency. You prepare for war in peacetime, hoping it will not happen. We must continue to plan for the next pandemic even as we go through this one, and not wait to be overwhelmed. The next pandemic may be round the corner and could be even more devastating than this one.”

Robin Shattock agrees that now is no time to relax. “Right now, everyone is thinking about infectious diseases, but I predict that it will only need a couple of years post-COVID for that interest to drop off rapidly. And the fact that the COVID vaccines were developed so quickly – and successfully – has set public expectations sky high. If we are to resolve huge challenges like antimicrobial resistance, we must use the resources gathered together through the Institute to keep the issue of infection at the forefront of our minds.”

Tackling leading threats to global health

Malaria and mosquito behaviour

Dr Lauren Cator

Working on how mosquito behaviour mediates interactions with other organisms, the parasites that they transmit and the dynamic world that they live in, analysing feeding and mating behaviours.

Self-amplifying RNA vaccines

Professor Robin Shattock/VaxEquity

A collaboration with AstraZeneca to further develop self-amplifying RNA technology, a temporary genetic code that can be used to train the immune system to recognise and respond to threats.

Mask design and 3D printing

Dr Connor Myant

Developing a quick and cost-effective design-through-manufacture process for making custom-fit face masks, in order to provide additional support to healthcare services during public health crises.

Rapid distinction between viral and bacterial infection

Dr Jethro Herberg and Professor Michael Levin

Developing a new test to quickly distinguish between viral and bacterial illnesses, and identify early cases of potentially deadly infections.

Malaria pathogenesis/treatment

Dr Aubrey Cunnington

Trying to better understand the host-pathogen interactions causing severe malaria in humans and to identify novel treatments which could be used alongside antimalarial drugs, with collaborations in West Africa.

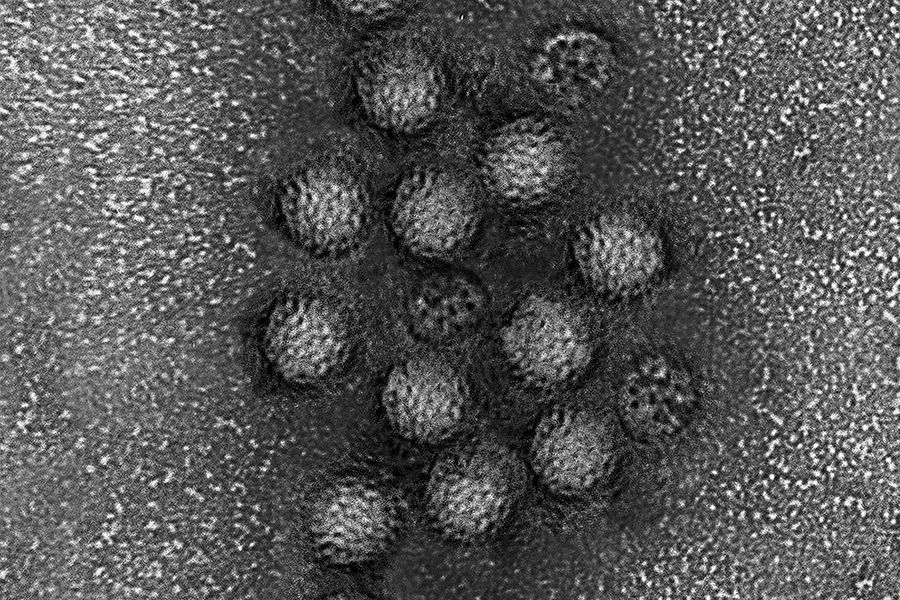

Digital diagnostics

Professor Pantelis Georgiou

Using groundbreaking lab-on-chip technology based on semiconductor technology, such as the revolutionary Lacewing platform, for genomics and diagnostics targeted at infectious diseases and antimicrobial resistance.

Epidemiology and modelling

Professor Christl Donnelly

Turning mathematical modelling from a theoretical tool for exploring transmission dynamics into an essential part of the armoury of governments and public health agencies responding to emerging epidemics.

Imperial is the magazine for the Imperial community. It delivers expert comment, insight and context from – and on – the College’s engineers, mathematicians, scientists, medics, coders and leaders, as well as stories about student life and alumni experiences.

This story was published originally in Imperial 52/Summer 2022.