Dr Paul Atherton

Paul co-founded his first company, Queensgate Instruments, while studying at Imperial in 1978. He planned on pursuing an academic career, but that all changed when he got a call from NASA, who wanted to use the Queensgate technology. After turning Queensgate Instruments into an optical fibre business in the 90s and selling the company in 2000, he continues to help start-ups at UK universities.

The start of Queensgate Instruments

Paul’s entrepreneurial journey began by accident. He and his co-founders were building optical interferometers for large telescopes, something people had been trying to do for 100 years without success. But with persistence and hard work, they came up with the technology to do it. Now they could study the night sky more effectively, doing things that would normally take days in hours.

And the technology was popular. Academics from prestigious research groups wanted the instruments. Paul and his co-founders would spend Saturdays building them and then taking refreshment in the Queen’s Arms pub, behind the Royal Albert Hall. “It was the watering hole for the physics department,” he remembers.

That’s when they decided to start a company: Queensgate Instruments. The founders agreed to invest £350 each in the company to get things going, with Paul borrowing his share from his grandfather. They paid themselves £5 an hour. “That seemed like a lot of money to an impoverished student in 1978!” he says.

With the physics department van, outside the pub near the Royal Greenwich observatory in 1976

With the physics department van, outside the pub near the Royal Greenwich observatory in 1976

A change of plans

Paul planned on pursuing an academic career and working for the company part-time. In 1985, he was about to start a professorship in the US. His plans changed when he got a call from NASA, who wanted to use Queensgate Instruments’ technology on a space shuttle. Paul took a year’s sabbatical to see this through. But in the end, he never returned to his academic career and stayed with the company full-time.

To help him run the company, he studied for an MBA at London Business School. “I was a fish out of water there,” Paul remembers. “They looked at me like I was some kind of weird animal - there were not many deep-tech start-up entrepreneurs around in those days!”

Selling the business

Paul and his co-founders ran the company for another 15 years, turning it into a fibre optic business along the way. “We knew optical fibre would be important in the future,” he explains, even if they didn’t quite know how. “We came up with a device that could be used in telecoms and that revolution came along in the mid-90s.”

A few years later, he came back from the US with a $50 million dollar supply contract. They got a factory, hired employees and within a year three major telecom companies were competing to buy Queensgate Instruments. They sold the business in 2000.

Lessons for aspiring entrepreneurs

After running a company for over 20 years and studying for an MBA, Paul learned several important lessons about being an entrepreneur. “London Business School was a revelation for me,” he explains. “I couldn’t understand what accountants were talking about. I didn’t know what deferred tax was.” But these weren't the most challenging things to learn.

The accounting stuff was easy. The people stuff was an eye-opener. Things like the hierarchy of needs, organisational behaviour, economics and marketing. They were valuable lessons. Things I didn’t expect to learn because I didn’t know they existed. Going there was like going to psychoanalysis every day.

We discuss several lessons Paul shares with aspiring entrepreneurs. The first is to act quickly. “In business, things always take three times longer than you think. And they’re always more expensive. Whatever you think you need to do, you should do it harder and faster than you think you need to.”

Another is to have a sense of foresight. But this is best kept broad. “You need to have faith your view of the future will come to pass. You might be wrong, but the world changes in fast and unexpected ways and sometimes you can be right. At Queensgate Instruments, we knew optical fibre devices would be needed, but not quite when or how.”

Thirdly, nobody should think they can get rich quick. “There are very few examples of people who do this, and most that do are lucky.” Rather than making a lot of money, Paul thinks start-ups should focus on making the world a better place. “Those are the things that excite me, when people want to help solve issues like climate change or cancer.”

Paul with Kerry O'Donnelly Weaver (MRes Chemical Biology 2011, PhD 2015) and Angela de Manzanos (MRes Chemistry 2012, PhD 2016) of FungiAlert. Paul is Chairman and Investor in FungiAlert, who have developed an award-winning, cheap disposable pod that alerts farmers to the presence of plant disease in the soil before infection occurs.

Paul with Kerry O'Donnelly Weaver (MRes Chemical Biology 2011, PhD 2015) and Angela de Manzanos (MRes Chemistry 2012, PhD 2016) of FungiAlert. Paul is Chairman and Investor in FungiAlert, who have developed an award-winning, cheap disposable pod that alerts farmers to the presence of plant disease in the soil before infection occurs.

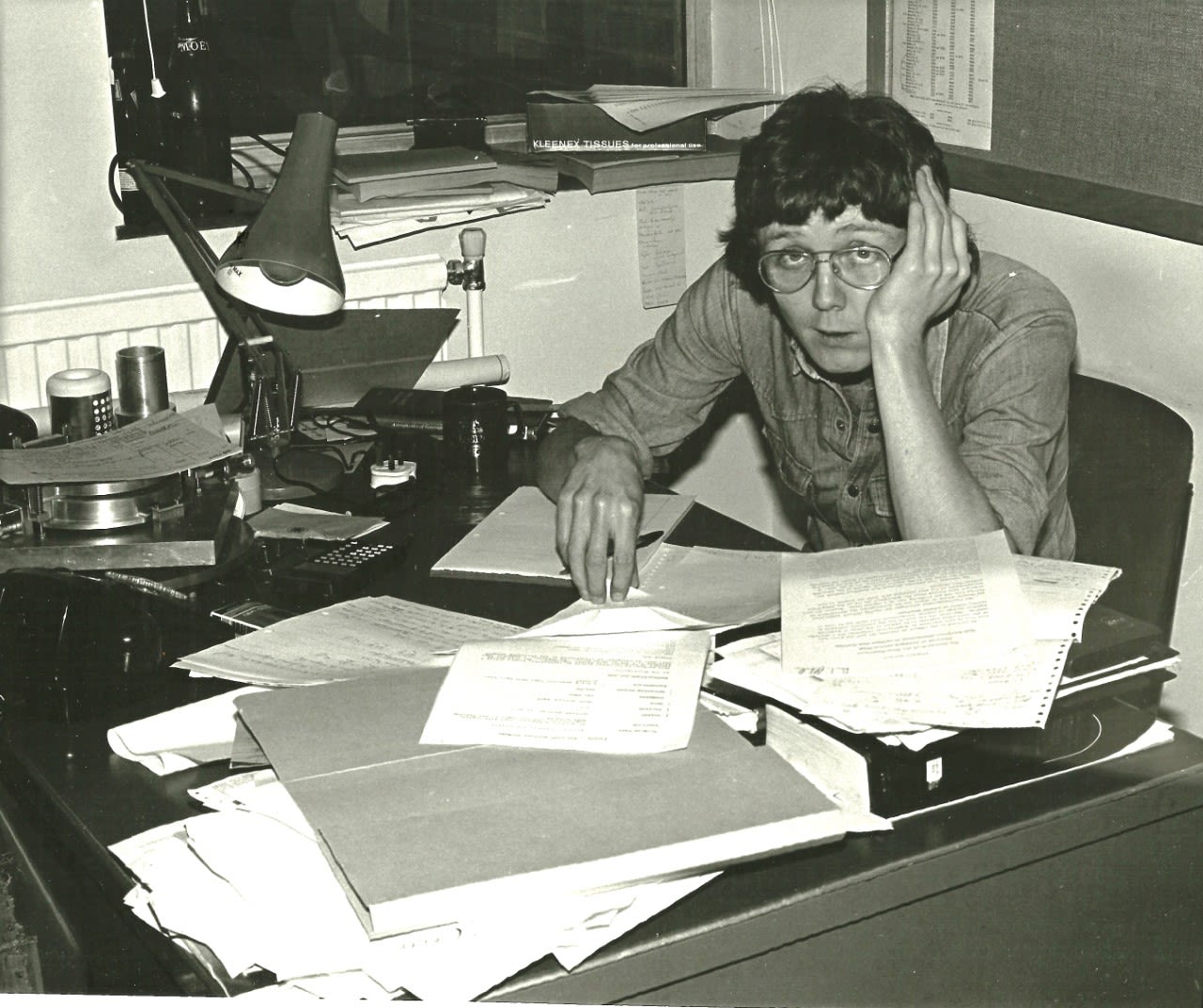

Paul writing up his PhD in Blackett Lab in 1978

Paul writing up his PhD in Blackett Lab in 1978

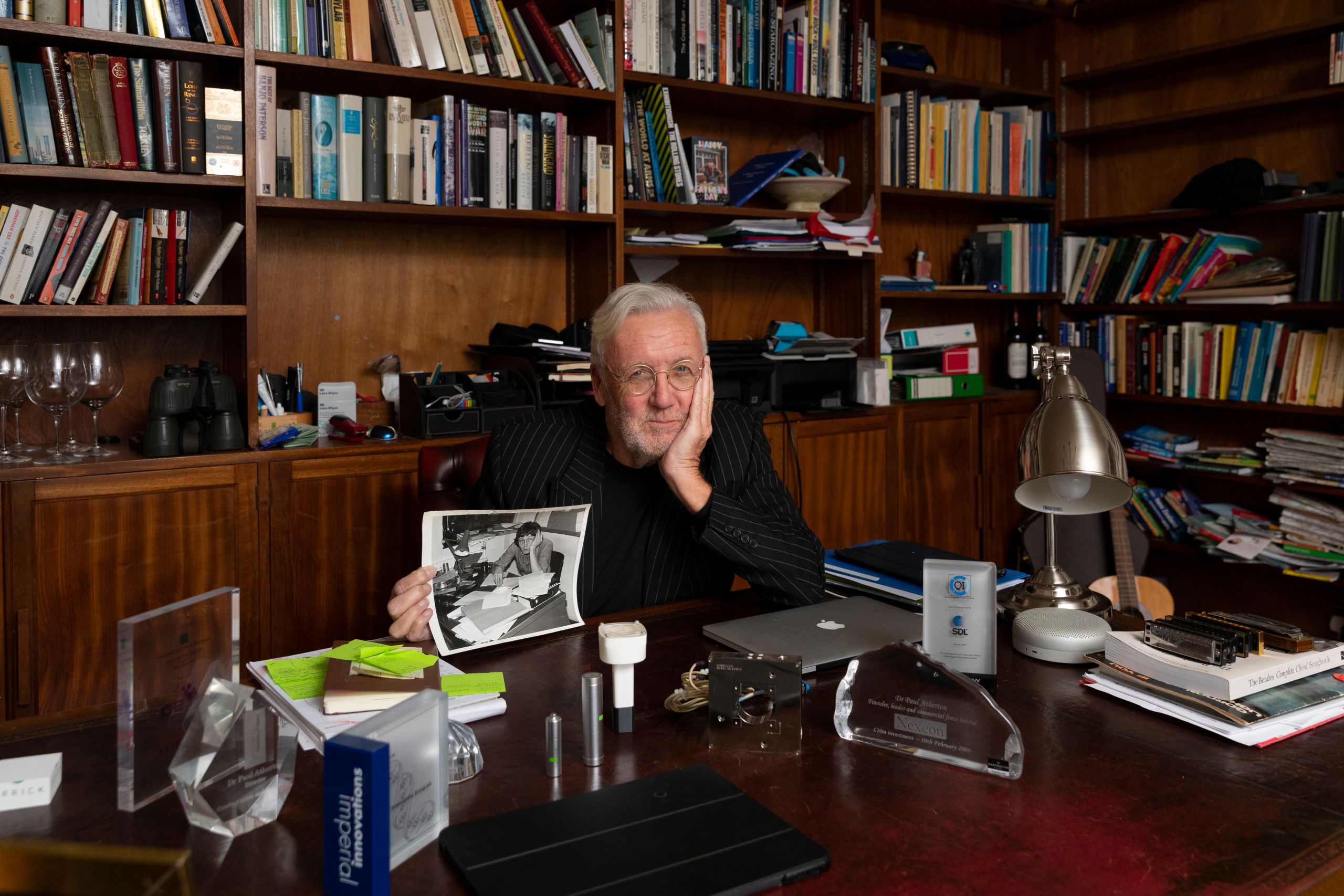

Holding a copy of that photo, Paul replicates the pose in his study at home in 2020

Holding a copy of that photo, Paul replicates the pose in his study at home in 2020

Inspiring trust

Of all the lessons we discuss, it’s clear getting people to trust you is the one Paul has the most to say about. He says playing chess helps. “You have to know what the other person is thinking. You have to be able to see things from their side of the board.” Paul believes this isn’t something you can learn from studying physics.

You’ve got to get people to trust you. They’ve got to believe what you sell them is going to work. Your employees need to trust you too. They’ve given up their jobs, they have mortgages and kids. You’ve got to show them you’re worth following.

How should aspiring entrepreneurs get people to trust them? By finding out as much about their customer as they can, and this may mean going out of your way. Paul remembers the story of an academic who needed a licence from the US for their start-up. But the person they needed to reach wasn’t answering their calls or emails.

“So, I said find a way to get to them,” Paul says. “That’s what I used to do. I’d never say I was only coming to see them. I’d say ‘I’m passing through and I want to drop by for coffee.’ They’d say that’s fine. There were lots of times I went all the way to Minneapolis or LA only to see them and they didn’t know that. It was the only way I got to see them. This approach might take a few days of your life, but it’ll get you somewhere.”

It can be eye-opening. “If you can go to someone else’s place for a meeting, you learn so much about them. What coffee they drink, what’s on the walls. At meals you learn about their families. You need to know what they’re worrying about. They’re thinking ‘how does this decision affect my career?’”

Sound risky? Not to Paul. For him, it’s all part of the job. “Entrepreneurs aren’t risk-takers. I’m like a mountaineer. I only climb with the right equipment and having looked at the weather forecast. It looks scary, but you don’t want to die doing it. You don’t take risks, you take action well-prepared and well-organised.”

Mentoring at Imperial

Paul regularly shares these lessons as a mentor, giving talks at Imperial College and London Business School. “I’ve founded numerous start-ups (including four from Imperial College) and played a significant role in these, mentoring chief executives on crucial decisions.”

More recently, Paul became the Founding Director of the Imperial Venture Mentoring Service, where entrepreneurs mentor students and staff in voluntary roles. “We get the pleasure of engaging with bright young people and helping them to do good things,” he says.

This is beneficial for everyone. “Ideas are cheap and easy. Doing things is the hard part. It’s useful to have experienced entrepreneurs who can help people avoid making common mistakes.”

Paul’s leadership has seen the Imperial Venture Mentoring Service (IVMS) scale to 75 mentors, helping ventures to raise over £17 million in grant and equity funding and gain access to prestigious accelerators fuelling their impact. Read more about IVMS’ impact.

Leaving a legacy

When he looks back at his career, Paul is surprised by how much impact his work continues to have. He tells the story of meeting a former colleague at a Royal Society gathering five years ago, who was writing a book on the great optical observatories of the world and taking photos of the labs and equipment they used.

Paul offered to sponsor the book if he could join him. What he saw on this journey was astonishing. “In two observatories, they had equipment I’d designed in 1985 still in use on the telescopes. I couldn’t imagine they’d still be using this stuff!”

Professor Richard Ellis and Paul with an instrument they designed in 1985, still in everyday use on the 6.5m Magellan telescope at Las Campanas in Chile

Professor Richard Ellis and Paul with an instrument they designed in 1985, still in everyday use on the 6.5m Magellan telescope at Las Campanas in Chile

I think of Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken. I’ve chosen a less traditional road than the academic path. And I think I’d tell my younger self that it’s going to be okay. An entrepreneur’s life suits you better.

Making the world a better place

Of all the things we discuss, it’s obvious that for Paul, making the world a better place is what matters most. And he’s happy to have the opportunity to do this through targeted start-ups.

“If I was an academic researcher, I’d be building technology to go on satellites. That would make the world better in a different way. But the start-ups I have founded are helping with things like climate change (Nexeon), cancer (Phase Focus), feeding the world sustainably (FungiAlert) and improving mental health (Delica). That’s what drives me.”

For me, life is about leaving the world a better place for my children and grandchildren and everyone in it. If I can do that through my activities, that would be wonderful.

Follow Paul's journey: visit his website paulatherton.com