Professor Sir Stephen Sparks

What we know about volcanoes today owes a lot to Stephen Sparks. His career has significantly advanced the fundamental science in this area and has helped develop hazard and risk assessment methods used around the world. He's also one of the small number of experts nations turn to for advice when an eruption is imminent and communities could be in danger.

Mountains, caves, picking up fossils and collecting rocks were all part of Stephen’s childhood. Little did he know this was the beginning of a lifelong interest that would take him across the world, from working on Monserrat in the Caribbean to speaking to school children in Geneva in his retirement. He has made significant contributions to research in this area, advised on its application and promoted natural science to the next generation.

I specialise in volcanology. My research seeks to explain the fundamental causes of volcanism, how volcanoes work, the dynamics of volcanic hazards and the elucidation of associated igneous processes.

The start of his journey

A pivotal moment for Stephen was securing a place at Imperial after Professor Wally Pitcher at Liverpool University encouraged him to apply. As a student he met the figures that inspired him, supported him, and gave him the foundation of knowledge he needed to break into the field.

Stephen owes much to George Walker, a world-renowned British volcanologist. His lectures inspired Stephen and three other students to organise an undergraduate expedition to Iceland for six weeks to study the volcanic rock. This trip confirmed for Stephen that he would dedicate his career to volcanology.

A career in a nutshell

After graduating from Imperial, Stephen went on to become an expert in geology with interests in volcanology, petrology, geophysical fluid dynamics and quantitative assessment of risk from natural hazards.

He held an 1851 Fellowship at Lancaster University before moving to the US to work at the Graduate School of Oceanography (University of Rhode Island) where he spent time on ships and took samples from the sea floor. Following this, Stephen was appointed as a lecturer in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Cambridge. He then became a professor in the Department of Geology at the University of Bristol and was given the opportunity to build up a world-class department as head.

Stephen stands next to experimental shock tube apparatus to simulate explosive eruptions in a Bristol lab in about 1991

Stephen stands next to experimental shock tube apparatus to simulate explosive eruptions in a Bristol lab in about 1991

Stephen retired in 2020, but his retirement is a bit different from the norm. You’ll still find him doing what he does best – carrying out research, sharing his knowledge and collaborating with others, such as working with University of West Indies colleagues on a new eruption on the island of St Vincent. He has held other roles including trustee of the Natural History Museum (2016-2022) and chair of the Museum’s science committee.

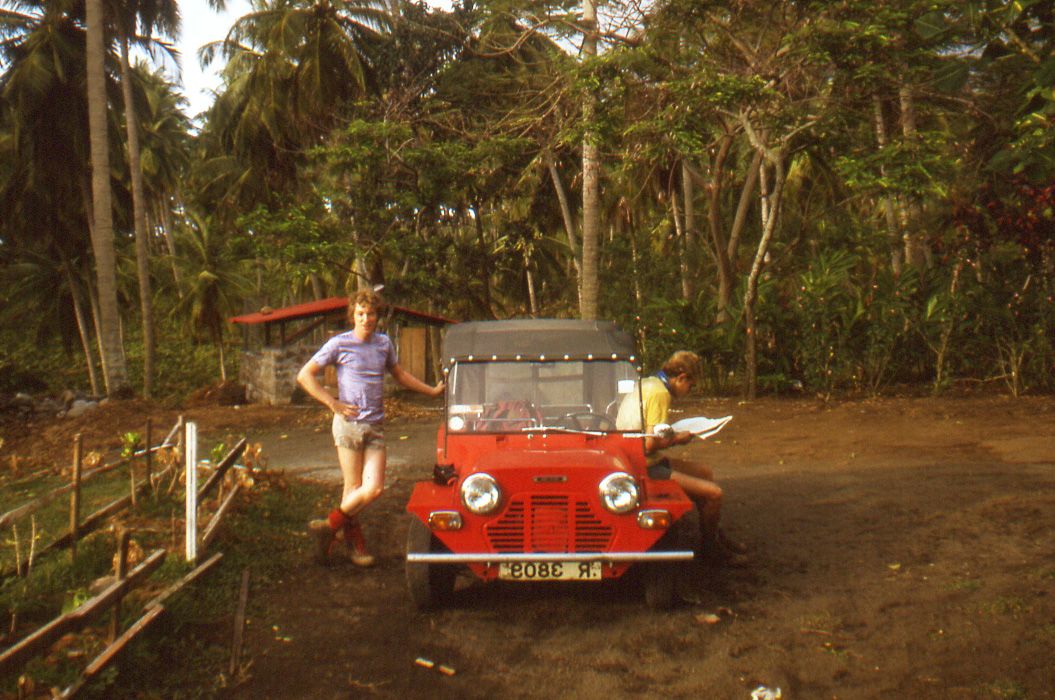

Stephen during field work in Dominica, West Indies in about 1977

Stephen during field work in Dominica, West Indies in about 1977

Field work on Merapi Volcano Indonesia with colleagues in about 2012

Field work on Merapi Volcano Indonesia with colleagues in about 2012

Field work in northern Chile, Andes in about 2002, repairing a road with postdocs and PhD students

Field work in northern Chile, Andes in about 2002, repairing a road with postdocs and PhD students

Pioneering spirit

A high point in Stephen’s career was his work during the eruption of the Soufrière Hills Volcano, Monserrat, between 1996 and 2011. He was one of the founding directors of the Monserrat Volcano Observatory and chaired the science advisory group, which was formed to support risk management on the island. After stepping down as chair, he continued to be a member for a number of years.

Monitoring and working on the volcano was really exciting science, but we were also involved in discussions with policy makers and gave advice to the government.

Collaborating with Willy Aspinall, Stephen pioneered new methods of hazard and risk assessment which informed decision-making on safety management during the emergency, including evacuations and informing long-term planning for the island’s future. The new methods to assess volcanic risk have been widely adopted in other volcanic crises and volcano observatories around the world.

A lifetime of achievements

Stephen has received prestigious awards including the Vetlesen Prize in 2015, which is widely regarded as equivalent to a Nobel prize for earth sciences. He also received a CBE in 2010 for services to environmental science and a knighthood in 2018 for services to volcano science and geology.

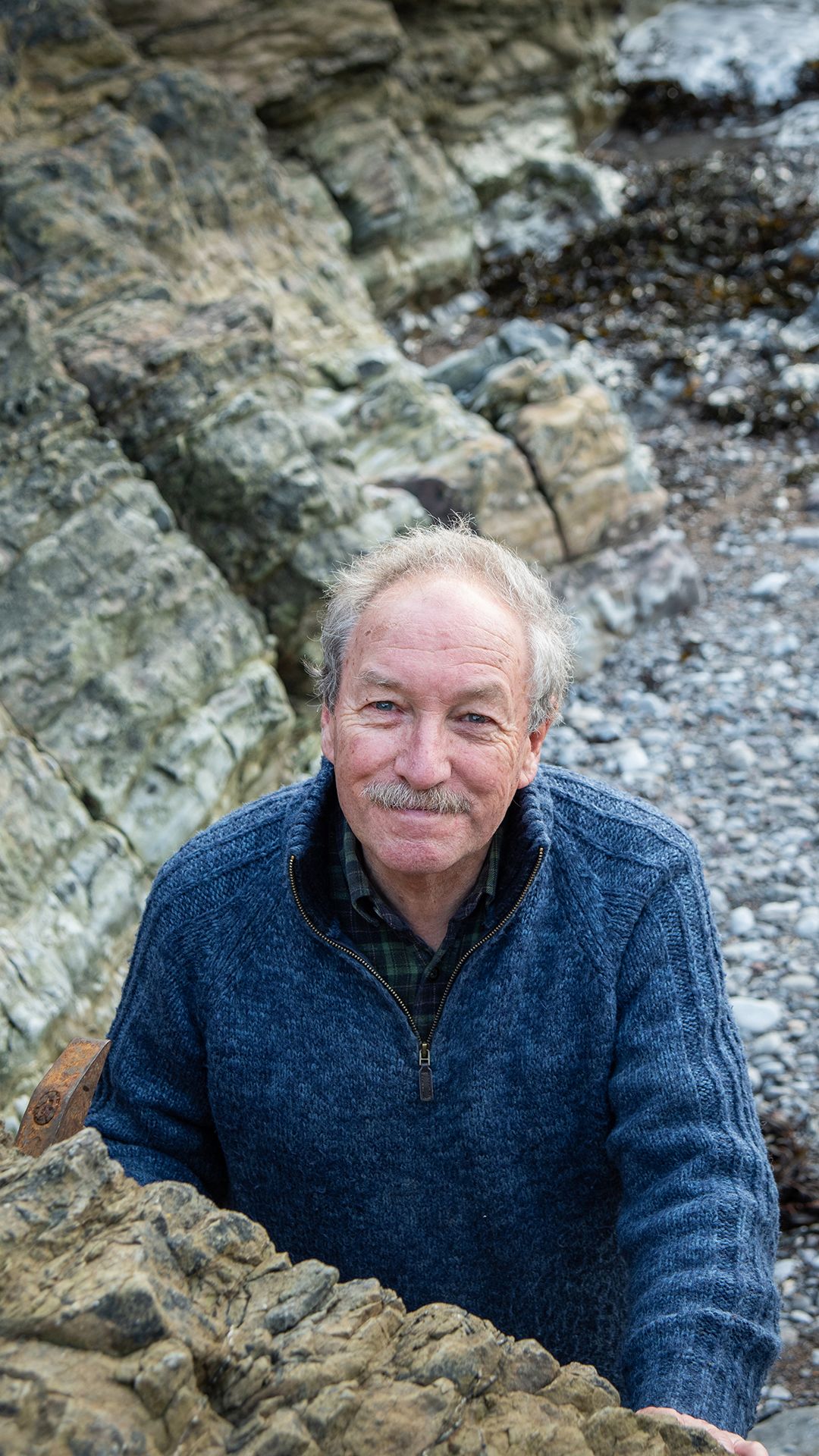

Taken by the Royal Society in 2014

Taken by the Royal Society in 2014

If you ask Stephen what he’s most proud of, he’ll respond that “it’s too hard to say”. Stephen explains, “My work has been very important for understanding volcanoes. There are more advanced techniques being used now, but my ideas turned out to be pioneering. My knowledge has also been used to give advice that has led to good government decisions.”

I would like to think I’ll be remembered for the fundamental science of how volcanoes work, but I hope there will also be some recognition for the work I’ve done to alleviate risk from hazards.

He highlights, “Sometimes the best advice is not to take action. In Monserrat in 1997, there was a huge political drive to evacuate the entire island. Some colleagues and I argued that the scientific evidence did not support full evacuation and our advice led to a good decision being made.”

More recently, Stephen has worked on a series of films on volcanic hazards for the public. These have been translated into seven different languages and have been an invaluable resource. “When a volcano erupted in Guatemala, some of the videos hit 2.5 million views in a very short space of time,” he shares. So, not only has his research informed the scientific world, but it has also helped people understand how to behave safely in times of crises.

Driven by curiosity

Like many other scientists, there is one thing that really drives Stephen – curiosity. “The things you don’t understand are more intrinsically interesting. When you find a solution, you then want to move on.” He continues, “Curiosity is something we need to encourage in schools. Science isn’t a series of known facts – it’s about trying to understand what is not yet understood.”

Stephen points out a big challenge for science is taking one area and applying it to others. An unexpected application of methods developed to assess volcanic risk emerged during the coronavirus pandemic. Stephen’s methods resulted in new data on close contact statistics of children within primary schools.

Working with epidemiologists, the risk assessment methods were adapted to assessing disease transmission in primary schools to compare the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies to reduce covid and limit the loss of education time in schools.

Collaborate with others

Stephen has one piece of advice, “Never think you can do it all yourself. Collaborating is extremely important, and it deserves more recognition. So often prizes are for individuals, not teams. Close collaboration with people with different perspectives is extremely useful.”

This has been reflected in Stephen’s career. In his early days as a geologist, he teamed up with Professor Herbert Huppert, a mathematician. Together, they built their reputation and used their joint expertise to boost understanding in the area. Throughout his career, he has worked with many other experts across the globe.

Stephen has also supervised 55 PhD students, with 16 now in established academic posts. He has also hosted numerous postdoctoral and visiting researchers from many different countries within the volcanology research group at Cambridge and then Bristol.

Stephen explains geology in the field in the Lake District in 2009

Stephen explains geology in the field in the Lake District in 2009

Geology is key

Stephen has worked with students of all ages – some as young as primary school age. He explains, “Lots of kids are interested in the environment – parts of earth sciences are very popular, but geology is not as popular as it used to be.”

I would say youngsters should have an open mind as we’re going to need geologists to solve the problems we’re facing. There are a lot of opportunities for good jobs and saving the planet at the same time.

“If we’re all going to drive electric cars then we are going to need to mine copper, lithium and cobalt. To do that, we need to dig them out of the ground and there’s a shortage of mining engineers,” Stephen explains.

A place close to his heart

He has many stories of his time at Imperial, but there is one that stands out. “I remember very vividly John Ramsey’s lectures. He was a brilliant scientist and is still regarded as one of the greatest in his field. He used maths to show us how rocks form, combining pictures and equations seamlessly. It showed me how valuable maths could be in this area."

Stephen says, “Imperial undoubtedly had a major influence on my career.” He keeps in touch with people he met – including the three students he went to Iceland with as an undergraduate.

I’m very pleased about this alumni award – it’s nice to be recognised by Imperial. I have a lot of affection for the place, and I still collaborate with people there. Student days are very formative, and I have a lot of fond memories from being a student in the late 60s and early 70s.

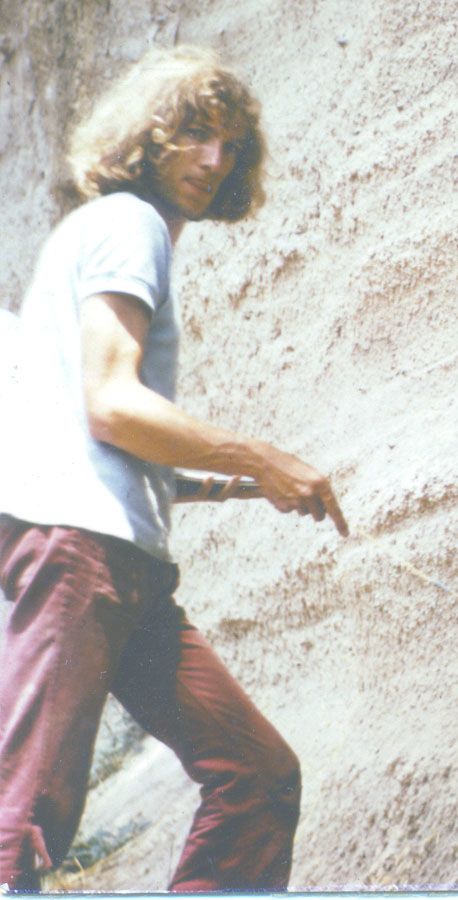

Stephen conducting field work in Italy during his PhD

Stephen conducting field work in Italy during his PhD

Despite retiring in 2020, Stephen continues to be actively involved in the field, whether that’s continuing research on understanding why volcanoes erupt episodically or advising during an explosive eruption or travelling to give a lecture to the public.

Follow Stephen's story:

Imperial's Alumni Awards recognise the outstanding achievements of our alumni community and the variety of ways they are making a real impact across the globe.

The Distinguished Alumni Award celebrates celebrates outstanding alumni who have demonstrated sustained excellence in their personal and professional achievements, are leaders in their field or have made a substantial impact on society.