Professor Sanjeev Gupta

Professor of Earth Sciences, Department of Earth Science

& Engineering

As part of a series on the people behind our world-leading research, we meet an Imperial geologist whose work spans continents, time, and even reaches out to Mars.

Time. Travel

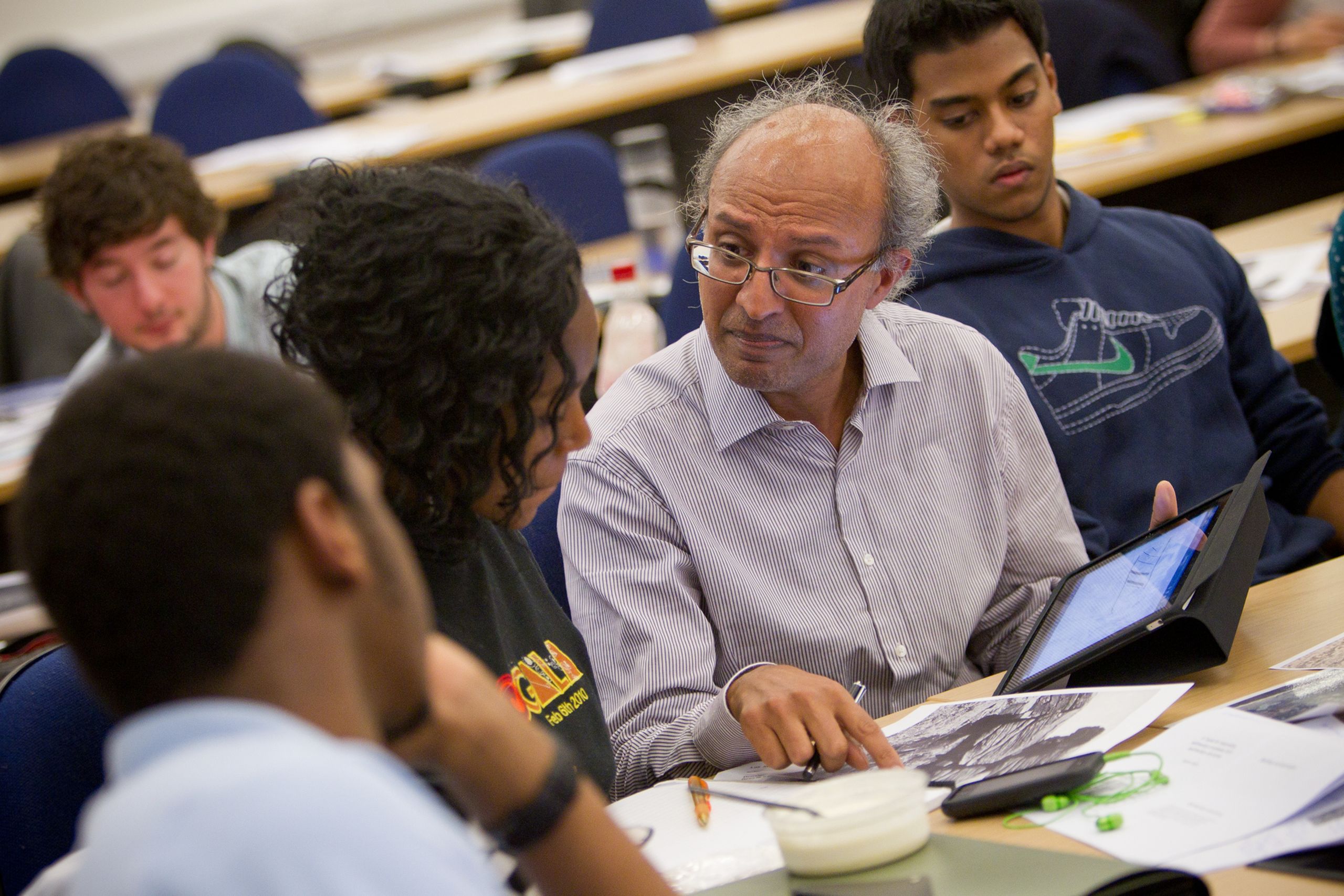

My work is all about solving problems. I reconstruct landscapes on Earth and on other planets through time.

It's like going to different places, but also going back through the farthest reaches of time. It’s trying to piece together what the Earth’s surface was like millions or billions of years ago, or what the surface of other planets are like, both today and in the past.

I was told ‘If you study geology you'll get to travel the world’ and it's absolutely true!

My parents wanted me to be a doctor, but I wanted to travel the world and go to remote places, and geology seemed a way of doing it. I was told ‘If you study geology you'll get to travel the world’ and it's absolutely true!

Problem solving

I really fell in love with the idea of doing research when I was at university. I was intrigued by problem solving, and geology has a lot of problems to solve which involve going to strange landscapes. You're sort of trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle. You have clues in the rocks and you're trying to reconstruct what happened.

I remember for my first paper, which was on river patterns in the Himalayas, I used The Times Atlas, which sounds completely ridiculous, but we didn't have [satellite imagery].

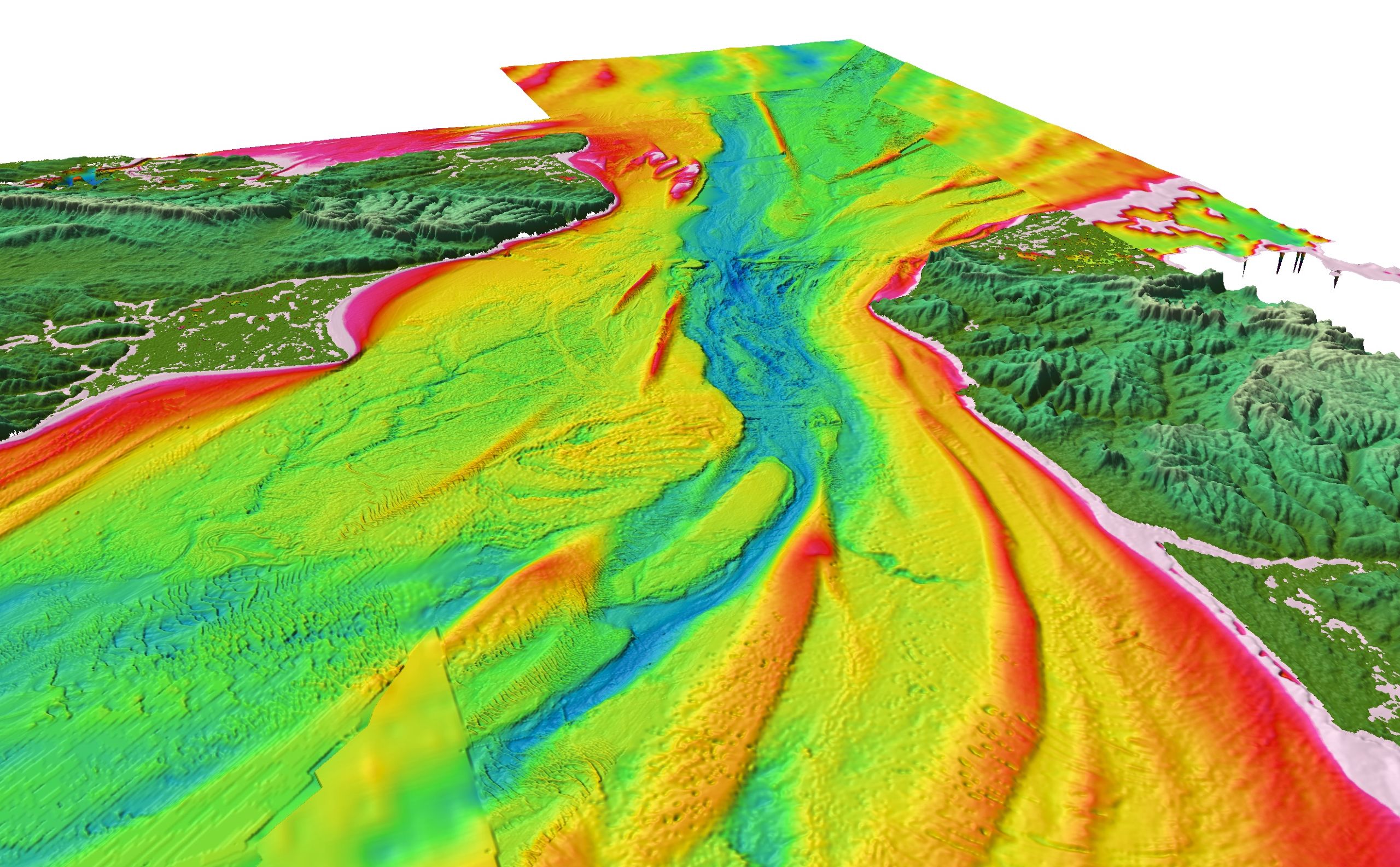

When I first started out, geology was very qualitative but now it's become much more quantitative. For example, one of the things I use now is detailed analysis of high resolution satellite imagery in my work on landscapes on Earth. But when I was doing my PhD, we didn't have these tools.

I remember for my first paper, which was on river patterns in the Himalayas, I used The Times Atlas, which sounds completely ridiculous, but we didn't have that high-resolution data. So we've seen a dramatic transformation.

Balancing the equation

Probably the biggest challenge as a researcher earlier in my career, I would say, has been juggling work and family life. I took quite a lot of time off when my children were young.

At times it was a little bit hard because you couldn't easily go to meetings or do fieldwork, or I would take my kids to meetings. I remember turning up at a big conference in Vienna once and the airline lost the buggy. I had to run to the meeting to give a talk with two children in tow, and no buggy!

The biggest challenge as a researcher... has been juggling work and family life.

It was challenging, but in some ways, taking that time off actually provided some time to think. Sometimes we're in such a hurry to do our research, you don't get that thinking time.

It's one thing that scientists and academics always complain about, that they don't have time away from the day-to-day stuff to think about problems and scientific questions.

A little bit of luck

People may not realise, but research is a little bit serendipitous.

You have to be a bit lucky in finding the research problem that's interesting, and then there's a bit of luck in actually managing to make it work out, and you don't know that at the outset.

The two pieces of work I've probably gained the most from personally were both kind of partly serendipitous.

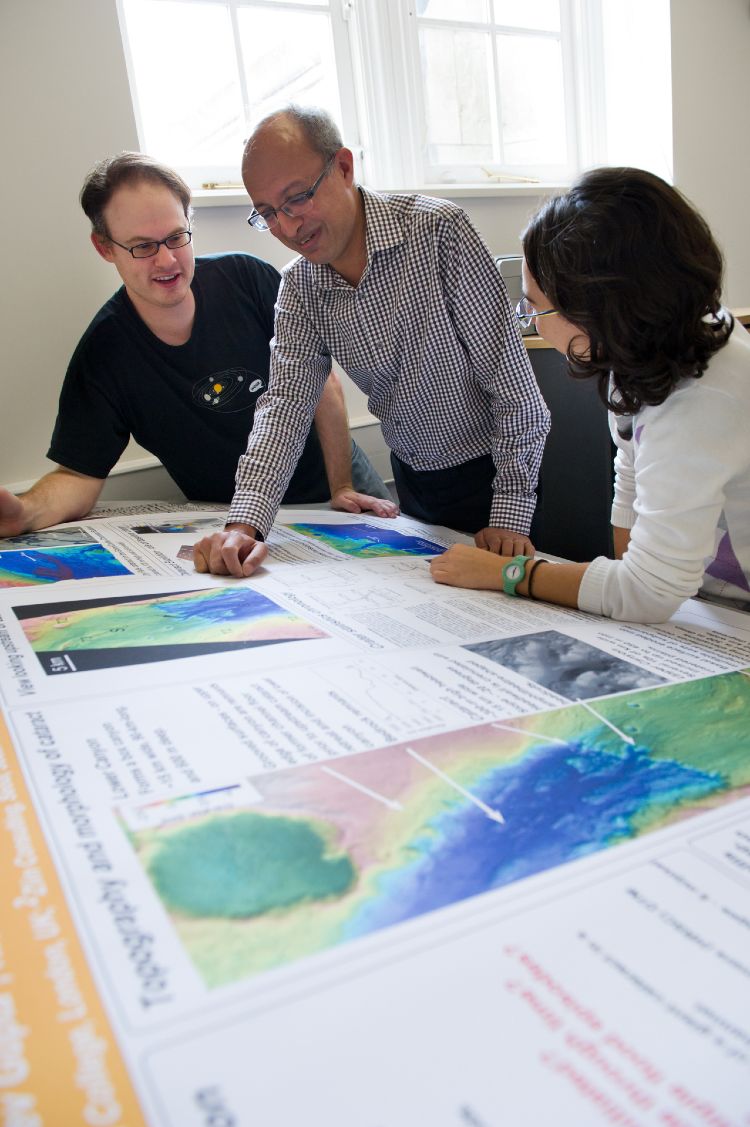

First, in the work I did with Professor Jenny Collier also here at Imperial, we were lucky to get funding to map the bottom of the English Channel.

During that project, we discovered that there was this question of how the Channel formed and how the Strait of Dover - the gap between Britain and France – was actually created.

We were very lucky in that we acquired data through other collaborations that really helped to solve that problem.

But there was a whole string of events that may not have happened if we hadn't pursued it, and I think the key thing with science is actually being persistent.

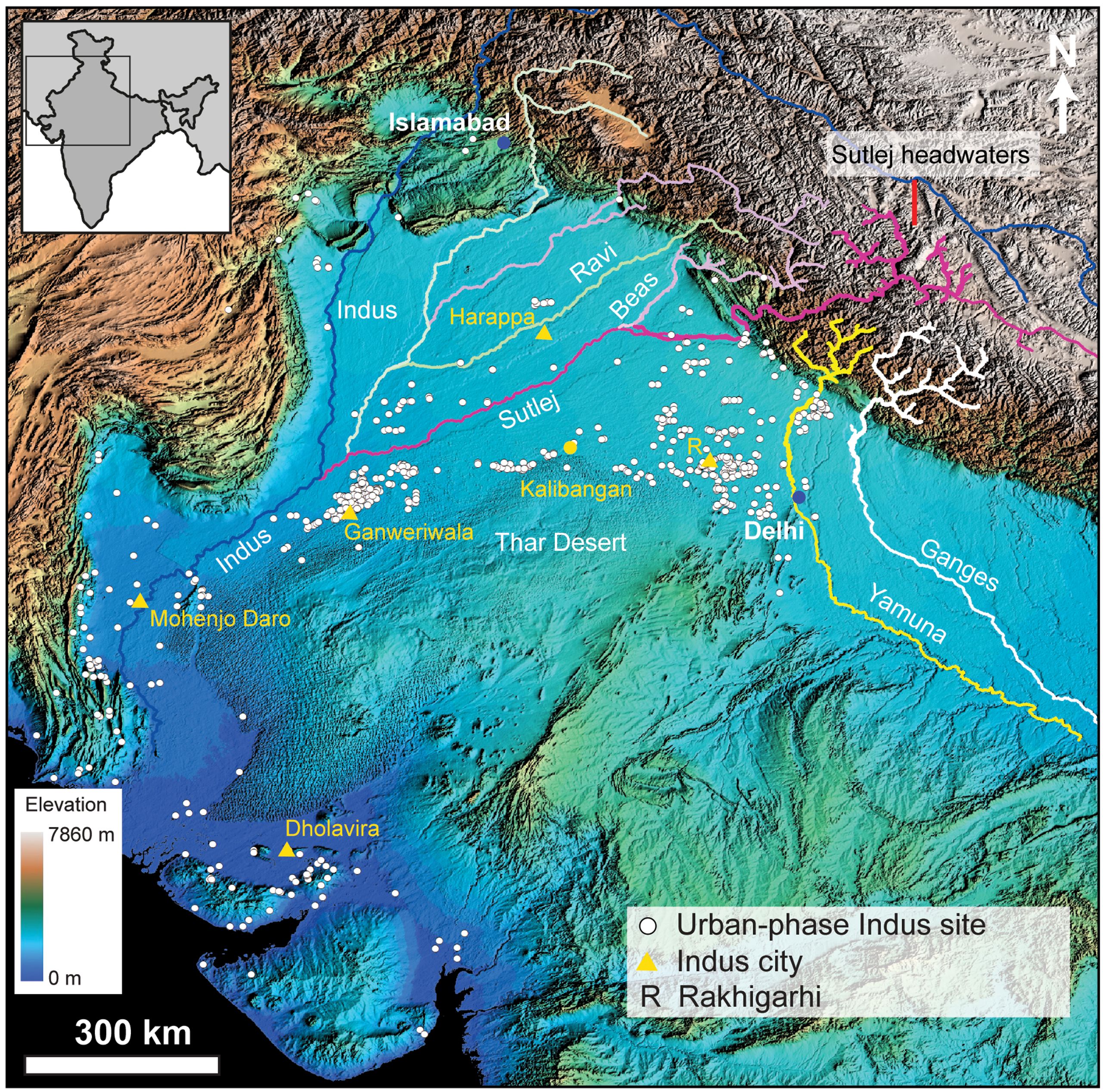

The second project was the work I've done with Dr Philippa Mason at Imperial and colleagues in India, the UK and elsewhere, on the Indus civilization.

On the satellite imagery we could trace these beautiful ancient river channels adjacent to archaeological sites. We wanted to test if there was a link between these rivers and the settlements of the Indus civilisation, that is did the rivers sustain the Indus people.

But we actually discovered that the river sediments were about 5000 years older than the archaeological sites, so the river had actually dried up by the time the Indus people moved from villages into living in small towns and small cities

It's really remarkable that they could sustain themselves probably just from monsoonal rainfall. If you think about the other civilizations like Egypt and Mesopotamia, they were sustained by big perennial rivers, the Nile and the Tigris and Euphrates, whereas this third major civilization in many areas of settlement was actually able to survive and exist on rainfall-fed agriculture.

Looking to Mars

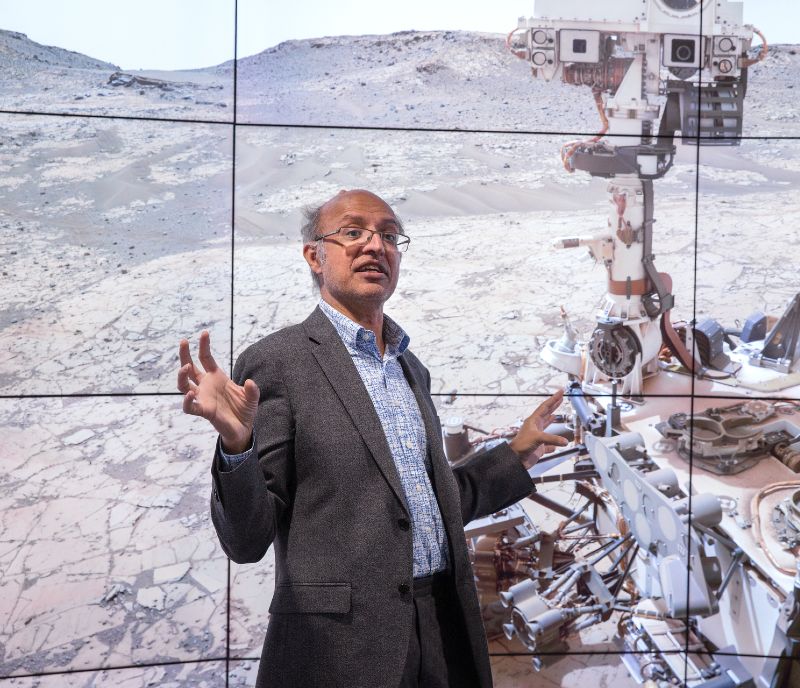

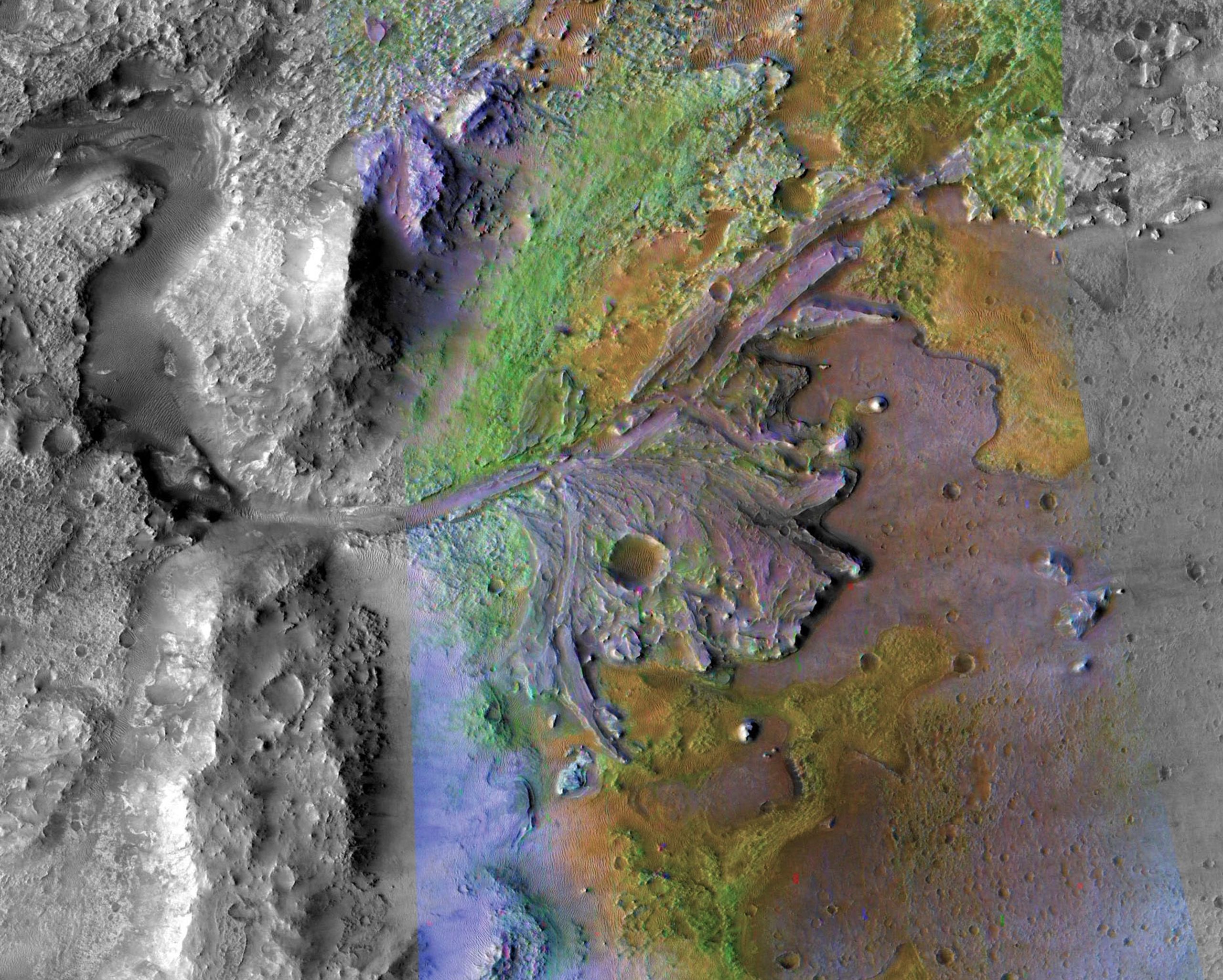

At the moment, my focus is on Mars. Again, through a series of serendipitous chances, I got involved with the Curiosity and Perseverance Rover Missions.

With Perseverance, it's very exciting as it will be collecting rock samples which will be brought back to Earth in about 10 years’ time. But thinking about where to sample is a very difficult question.

My daughter can't believe that I get paid to look at pictures of rocks on Mars, but that’s what I do!

If I'm collecting samples in the Alps here on Earth, and I find a better rock, I can swap out the old one for the new one. We can't do that on Mars. Once we've collected a sample and it’s inside the Rover, it's there. So it's a difficult decision: ‘shall we sample? Shall we not?’

My daughter can't believe that I get paid to look at pictures of rocks on Mars, but that’s what I do! I use my knowledge of the rocks and environment on Earth to make interpretations of the Martian rocks.

For example, Perseverance is just about to start exploring this major delta system in Mars’ Jezero Crater, that was once fed by rivers that built out into a lake in the crater.

Recently, I went to Greece where we have beautifully preserved rock exposures of ancient delta systems, and it's just remarkable how similar those rocks and deltas in Greece look like the ones we find in Jezero Crater. They could be identical.

Mars is dry, cold, arid, dead. But we believe that early in its history there was an atmosphere.

It was warmer and wetter and produced features similar to on Earth. We can use those analogues to help us understand more.

We have to be careful as they may not be exactly the same, but there's so many similarities now that Mars doesn't feel like a completely alien world anymore.

Curiosity and perseverance

In terms of advice for others, I would say just be curious. Chase interesting problems. And keep at it. Persistence is the most important thing.

It's quite easy to have an idea, but it can be hard to work out how to solve a problem. You can't just do it by yourself. You have to find the right experts who can help you solve that problem.

The first few times we applied for a grant proposal for the Indus civilisation research, we were rejected, and I thought ‘well, I'm not going to give up because this is actually an interesting problem’.

Our work on the Indus has actually had quite a big impact. It led to NERC- and Indian Government funded research on groundwater depletion in NW India because when we were doing fieldwork, farmers told us about the groundwater problem. This research has led to several important publications and led to us running some policy workshops in India

So something that started as weird and a little bit niche research on the links between rivers and the archaeology of an ancient civilization has led to a whole series of papers that have had a big impact on environmental problems of groundwater depletion in NW India, and that's just by being persistent and chasing interesting things.

Professor Sanjeev Gupta is Royal Society Leverhulme Trust Senior Research Fellow within Imperial's Department of Earth Science & Engineering.