Professor Michele Dougherty talks about space missions and her first telescope

An Imperial scientist who is leading missions to Saturn and Jupiter has been awarded a prestigious Research Professorship by the Royal Society.

Professor Michele Dougherty FRS is the Principal Investigator for the magnetometer instruments for two major outer planetary space missions: the NASA Cassini spacecraft, which is in orbit around Saturn; and the European Space Agency JUICE spacecraft that is due to go into orbit around Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, in around 2030.

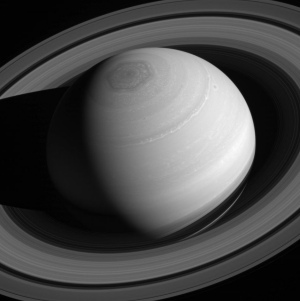

Saturn (photo credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

The Royal Society Research Professorship, announced today, provides long-term support, enabling world-class scientists to focus on their research. Appointments are usually made for up to ten years. Just two Research Professorships have been awarded this year, with the other going to Nobel-prize-winning physicist Professor Sir Konstantin Novoselov FRS.

Laura Gallagher caught up with Professor Dougherty, who is based in the Department of Physics at Imperial College London, to find out more about her exciting career and how she got here.

When did you first become interested in science?

“As a young child my dad built a telescope, and he ground the mirror himself, and my sister and I mixed the concrete for the base of the telescope. So the first view I had of Jupiter and its moons, and of the rings around Saturn, was through the telescope in our front garden.

“I never thought I’d work with anything like that because I didn’t do science at school – I went to an all-girls’ school in South Africa and it wasn’t usual for girls to do Physics in those days. But I was quite good at Maths and so I persuaded the University to let me do a BSc. And every day in the first year I’d go home and my dad would go through the Physics lectures with me, because I didn’t understand anything, so the first year was really difficult, but after that I felt I could do anything.”

How did you come to work in space physics?

“Even though I was really interested as a kid, because we had the telescope, I never thought I’d end up in space physics – it was a roundabout route that brought me here. My PhD was in applied mathematics.

“When I came to Imperial, a few years after finishing my PhD, I was going to stay on the theory side, but then I was asked to spend a little bit of time putting a magnetic field model together to look at Jupiter, because there was a spacecraft flying past Jupiter. So I started spending one day a week working on that.

“After working on that mission my former boss David Southwood went to the European Space Agency. He was the Principal Investigator on the magnetometer instrument on Cassini and he asked me to start taking that over from him.”

What have been the best moments of your career so far?

“I think there are two, both linked to the Cassini mission. The first was when we all went to the Jet Propulsion Lab to watch the spacecraft when it first went into orbit around Saturn, six and a half years after the spacecraft had launched. That was really scary, because there wasn’t direct access between the spacecraft and the Earth at the time, so a very small signal was sent that was telling us that it was on the correct path. And we were all at the Jet Propulsion Lab, watching points on this plot, and for 40 minutes we weren’t sure it if had actually gone into orbit. When it did it was such a relief.

“I think the second most exciting thing is this: my team on Cassini was responsible for discovering an atmosphere on one of Saturn’s moons. We saw some observations on two of the flybys past the moon and it looked like an atmosphere. We weren’t sure, but we thought it was important that we try to go really close on the next fly-by. And so on the next flyby, instead of being a thousand kilometres away, we persuaded the Project team to take the spacecraft realyy close, at 170km away from the moon.

“I watched the data coming back with my heart in my mouth because if we had messed up no one would have ever believed me again! So that was another of the exciting bits. And then we started putting all of the data together.”

What are you looking forward to doing over the ten years of your Royal Society Professorship?

“I am looking forward to having the time to do research, although I love teaching. I think the scariest thing I ever do is teach 250 undergraduates, but I will miss it.

“Cassini has another three years to run, and then the spacecraft will burn up in the atmosphere of Saturn. We’ll get really close and be able to measure the internal planetary field, something that we don’t yet understand. The Professorship will allow me to really focus on the science and it will also give me time to make sure we build the best instrument for JUICE, the mission to Jupiter.”

What do you particularly hope you’ll be able to figure out in the coming years?

“To try and understand how long a day on Saturn is, because that’s something we don’t yet know. To try and understand its internal magnetic field – we don’t understand that either!

“For JUICE, we want to go into orbit around one of Jupiter’s moons, called Ganymede. What we want to do is to measure the currents that are flowing in the liquid ocean underneath the surface because if we can do that we can work out how deep the ocean is – if it’s made of water and if there’s salt in the water.”

Photograph of Professor Dougherty reproduced courtesy of the Royal Society.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Laura Gallagher

Communications Division