Exploring Imperial's Chinese collaborations in data science and medical robotics

The Data Science Institute and Hamlyn Centre are two Imperial facilities with notable links to China, whose research work is having an impact globally

In the past decade Imperial has cemented its place as the UK’s number one research collaborator with China – with more than 2000 high impact academic papers published with Chinese partners in this time. Imperial’s Chinese research partners include businesses like Huawei, as well as scientific institutions such as Tsinghua University, Zhejiang University, Shanghai Jiao Tong, Wuhan and Peking Universities, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The nature of this work is incredibly broad and covers cutting-edge research in nanotechnology, bioengineering, computing, data science, advanced materials, offshore energy, environmental engineering and public health.

As part of his recent visit to the College, the President of China, Xi Jinping, was given a tour of two Imperial facilities with notable links to China: the Data Science Institute and Hamlyn Centre − both of which were given a recent boost following the announcement of a £3 million donation from the China UCF Group.

As part of his recent visit to the College, the President of China, Xi Jinping, was given a tour of two Imperial facilities with notable links to China: the Data Science Institute and Hamlyn Centre − both of which were given a recent boost following the announcement of a £3 million donation from the China UCF Group.

We took a closer look at both of the facilities and their collaborative projects.

Head for figures

Launched in April 2014, Imperial’s Data Science Institute was conceived with multidisciplinary collaboration at its very core. One of the headline projects seeks to understand, and in some cases predict, the complex interplay between a country’s physical infrastructure and various characteristics and behaviours of its population. The team at the DSI are applying models to both China and its neighbours and partners along the historic ‘Silk Road’ ancient trade route.

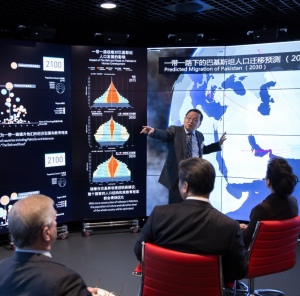

Professor Yike Guo presents to President Xi Jinping

Working with a raft of collaborators, and particularly Zhejiang University and the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital in Vienna, the project draws upon 50 years’ worth of stored data on infrastructure, GDP, demographics, education profiling and much more.

“What we are chiefly interested in is human development,” says Professor Yike Guo, Director and Founder of the Data Science Institute. “So for example, if you were to built a 2500 km railway in Pakistan, how might the education of people be affected along the route? What about birth rate and life span? Will each age group be affected in the same way and will there be gender disparity? It’s the first time such a model has been used to derive causality in this way.”

We are chiefly interested in human development

– Professor Yike Guo

The project is by its very nature ongoing and evolving and resulting models and simulations can be used by local and central government officials in China and elsewhere to assess the impact of certain policies.

“This is just the beginning,” says Professor Guo. “We are starting with the macro picture but it will gradually become more and more fine grained, such that we could even ascertain what the effect of the speed of a rail line might be on the population.”

Drawing upon Imperial’s expertise in Railway and Transport Strategy Centre (RTSC), the DSI is also building models of passenger flow in the Shanghai Metro and 8 other urban rail systems in China.

By collecting secondby-second entry and exit data at every single station, they can build up a picture of how the network behaves, for example predicting the effects that closing a station has on load distribution.

“This has real value in managing city transportation, helping to ensure efficiency, safety and security,” says Yike.

With the explosion of genomics and biomarker data in medical research, the DSI is helping to ensure its full potential and bring personalised, precision medicine to the wider population. They are developing innovative ways to allow medical researchers to see new patterns within their existing data to identify medically interesting subgroups of patients that do not respond to current therapeutic regimes. They are also helping discover the genes and proteins and explore the DNA mutations that drive their particular disease and visualise the perturbations of their molecular pathways.

With the explosion of genomics and biomarker data in medical research, the DSI is helping to ensure its full potential and bring personalised, precision medicine to the wider population. They are developing innovative ways to allow medical researchers to see new patterns within their existing data to identify medically interesting subgroups of patients that do not respond to current therapeutic regimes. They are also helping discover the genes and proteins and explore the DNA mutations that drive their particular disease and visualise the perturbations of their molecular pathways.

Recently the DSI secured a deal to work with Genomics England to provide the software platform for managing data from the 100,000 Genomes Project. Formally launched by the Government last year, the project aims to sequence 100,000 whole genomes from NHS patients by 2017, with the goal being to understand the differences between people’s genetic code that leads to disease.

“That is a major project that will have an impact internationally and a significant achievement for the DSI – reflective of where we are heading,” says Yike.

Human-machine cooperation

The Hamlyn Centre was established to develop safe, effective and accessible technologies that can reshape the future of healthcare for both developing and developed countries. Led by Director and Co-Founder Professor Guang-Zhong Yang, Hamlyn is at the forefront of research in imaging, sensing and robotics for addressing global health challenges.

Professor Yang (R) with President Xi Jinping

One of the main goals of medical robotics research at the Hamlyn Centre is to develop smart, cost-effective tools that enhance the ability of surgeons. These solutions incorporate a degree of intelligence and autonomy to assist the surgeons in achieving ultraprecision tasks, thereby improving safety and consistency.

One example of a bespoke robotic surgical solution being developed at the Hamlyn Centre, involves a procedure to unblock the main artery serving the heart through the insertion of a stent.

At present the surgeon makes a small incision in the groin and feeds through a catheter manually by hand, largely judging position by touch and feel – with the help of X-ray fluoroscopy imaging. “It requires considerable skill, something that really only the senior surgeons can do after performing hundreds of these operations; the learning curve for surgical interns is very steep indeed,” says Dr Su-Lin Lee (Computing) who is a researcher at the Hamlyn Centre.

Using a small robotic wire-feeder Su-Lin (left) is trying to automate the navigation procedure. She takes data from MRI scans of patients’ main blood vessels then programmes the robot’s ‘brain’ so it knows the path the catheter must take through the body – even taking into account for deformation of vessels due to breathing.

Using a small robotic wire-feeder Su-Lin (left) is trying to automate the navigation procedure. She takes data from MRI scans of patients’ main blood vessels then programmes the robot’s ‘brain’ so it knows the path the catheter must take through the body – even taking into account for deformation of vessels due to breathing.

“The robotic navigation techniques we’re developing should allow for a more consistent procedure with greater stability and easier manipulation,” says Su-Lin, who has been testing her system with model vessels and hopes to move to patient trials soon.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Andrew Czyzewski

Communications Division