First science data from Solar Orbiter shows Imperial instrument working well

Imperial’s instrument on the Solar Orbiter spacecraft was the first to turn on, sending back data that shows it working ‘far better than expected’.

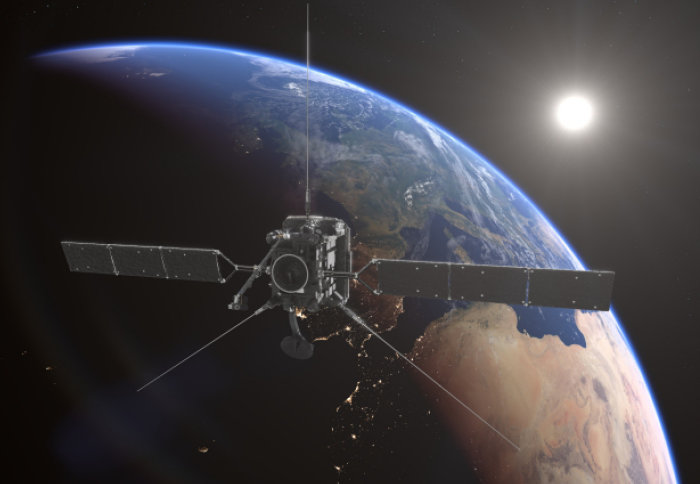

Solar Orbiter, ESA’s new Sun-exploring spacecraft, launched on Monday 10 February carrying ten instruments, including a magnetometer built at Imperial.

We are delighted with the measurements and the performance of the instrument – it looks even better than we hoped it would. Helen O'Brien

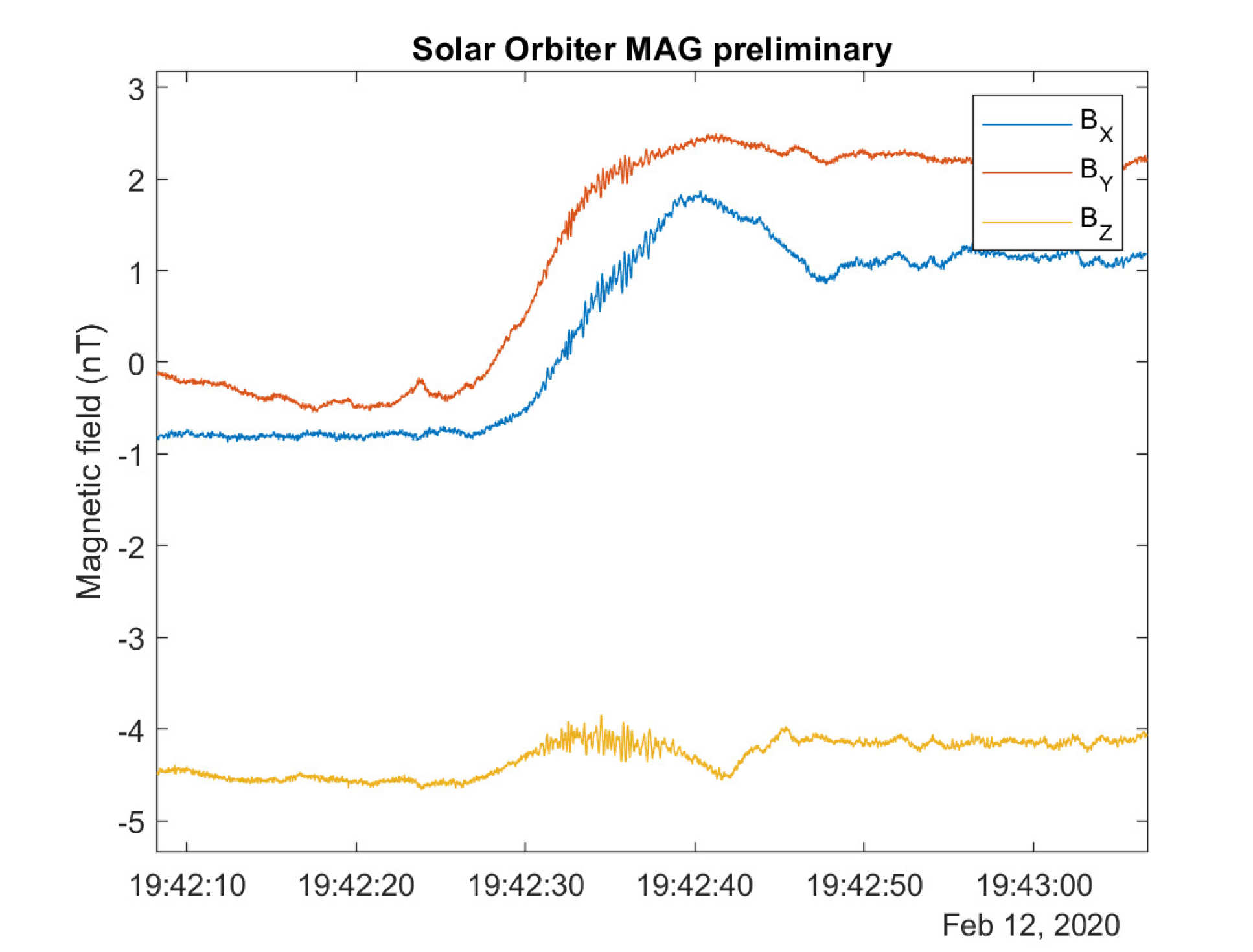

The magnetometer was the first instrument to switch on, less than 24 hours after launch, beaming back ‘housekeeping’ data showing it was alive and functioning. Three days later (13 February), it sent down its first science data, representing magnetic measurements in the solar wind, one of the main targets of the Solar Orbiter mission.

Solar wind fills the solar system with charged particles and the Sun’s magnetic field, which can interact with the Earth’s magnetic field. This can cause issues for power grids and electronics on Earth, as well as satellites and astronauts in space.

Outstanding data

Helen O’Brien, instrument manager for the magnetometer from the Department of Physics at Imperial, said: “It’s early days, but the data we have so far looks good. We are delighted with the measurements and the performance of the instrument – it looks even better than we hoped it would. We’re really excited to be entering the science phase and confident it can carry out its mission well.”

Professor Tim Horbury, Principal Investigator for the magnetometer from the Department of Physics at Imperial, said: “We spent a long time developing the instrument and it looked good in all the tests we did on the ground, but you never can tell until you get to space.

“We only have two hours of data so far, but it looks outstanding. The instrument has been well behaved and done all we asked of it. It looks like we will be able to do everything we need, and the instrument will be a key contributor to the science of the mission.”

Helen and Tim were at a party the evening after launch at Cape Canaveral in Florida when they got the news of the first ‘housekeeping’ data showing that the instrument was alive. Back in London, Vincent Evans and Isaias Carrasco-Blazquez received the data at Imperial directly from ESA’s computers.

Isaias spent a year and a half writing the software on the instrument that would gather and send the data, and he and the team worked with ESA to design a procedure for turning it on and gathering data in these first crucial hours.

He was working at home, in the early hours of the morning of 10 February, when he got the housekeeping data. He said: “I saw the first data while I was alone and had a small celebration to myself. It’s incredible to see my software working in space.”

Measuring the solar wind

This first data was sent back on a low-bandwidth antenna and arrived instantly. The first science data, however, had to wait until the high-gain antenna was deployed and came down two days later.

The magnetometer sits on a long boom at the back of the spacecraft, to keep it away from the other instruments, which could interfere with its readings. The whole spacecraft, which was constructed by Airbus in the UK, and all the separate instruments, had to be very magnetically ‘clean’ – produce no magnetic field of their own – for the magnetometer to work at its best.

Professor Horbury said: “We are grateful to everyone at ESA and Airbus who worked so hard to make sure the spacecraft was magnetically clean, allowing us to get this beautiful data.”

The magnetometer made measurements before and during deployment of the boom, measuring signals from the spacecraft to begin with, before taking its first pristine measurements in the solar wind.

The instrument will now switch off for a couple of weeks, but the team say the data they have already will keep them very busy until then.

-

Find out more about Imperial's contribution to the Solar Orbiter mission in our interactive feature.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division