Climate change added $4bn to damage of Japan’s Typhoon Hagibis

by Simon Levey

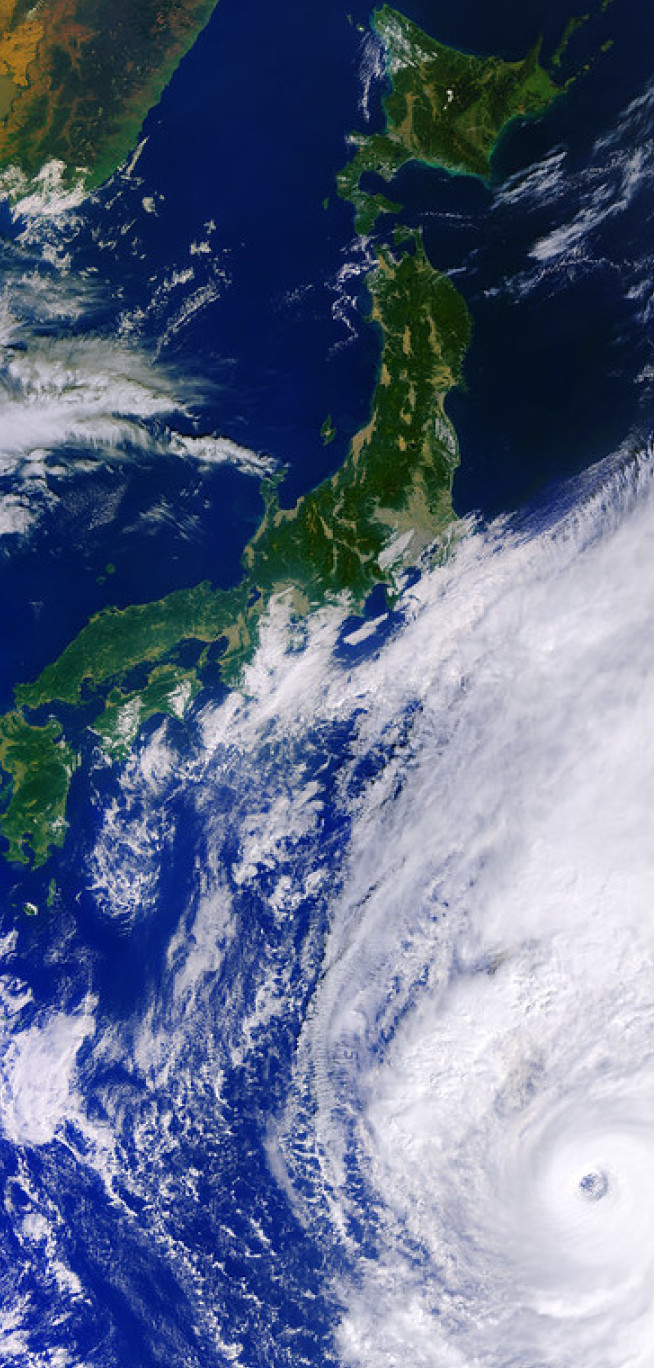

Damage caused by Typhoon Hagibis, Japan, October 2019 (Credit: m-louis / flickr CC-BY-2.0)

New study calculates how much of the damage of individual extreme weather events can be attributed to human-caused climate change.

The extreme rainfall that hit Japan during Typhoon Hagibis in October 2019 was made 67% more likely by human-caused climate change, according to analysis by scientists at Imperial College London and the University of Oxford.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change, also found that this increase in rainfall meant that $4 billion of the damage caused by the storm can be attributed to climate change.

Typhoon Hagibis was one of the most damaging storms in Japan’s history.

More than 240mm of rain fell in the Tokyo region on 12 October 2019 -- the highest since reliable records began in 1976 -- leading to around 100 deaths and causing significant destruction that made it the second-costliest Western Pacific typhoon on record.

To quantify the effect of climate change on this extreme rainfall, the scientists -- led by Dr Friederike (Fredi) Otto, Senior Lecturer at the Grantham Institute - Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London and Dr Sihan Li, Senior Research Associate at the University of Oxford -- analysed observations of the extreme rainfall during Typhoon Hagibis using records from weather stations operated by the Japan Meteorological Agency to characterise the event.

They then compared how rare this event is in computer simulations of the climate as it is today, with more than 1°C of global warming, with the likelihood of such an event in the climate as it would have been without human influence, using the same methods as in past peer-reviewed event attribution studies.

Their analysis found that human-caused climate change increased the likelihood of the extreme rainfall on 12 October 2019 by about 67%, reflecting the fact that a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, meaning storms like Typhoon Hagibis have the potential to drop more rain as global temperatures increase.

The scientists also calculated that $4 billion of the $10 billion damage in insured losses caused by the rainfall can be attributed to climate change.

Dr Sihan Li, Senior Research Associate at University of Oxford, co-author of the study, said: "Not acting against climate change will be much more expensive than reducing emissions and adapting to a warmer world. We are already seeing the costs of the action to cut emissions in the past, and the sooner net emissions are eliminated, the lower the damages from climate change will be."

This is the first study, for any extreme weather event in Japan, to calculate the damage attributed to climate change, and may underestimate the influence of climate change as observed extreme rainfall in Japan has increased by more than climate models simulate.

The results reflect the growing economic burden that Japan - and other countries - already face from climate change and will increasingly experience if emissions are not rapidly eliminated: the 'costs of inaction'.

The study looks at how much climate change increased the damage from just one extreme event, but as temperatures rise Japan is being hit by a growing number of extreme heat waves and heavy rainfall events (external link - PDF). With slow action to cut emissions and limit further warming these events and their economic burden would likely become increasingly severe.

Dr Friederike (Fredi) Otto, Senior Lecturer at the Grantham Institute - Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London, lead of World Weather Attribution, and co-author of the study, said: "The negative consequences of the continued burning of fossil fuels are now evident and can be felt also in wealthy countries like Japan. Storms like Hagibis have become more dangerous and destructive because of climate change, while other research has shown that the deadly 2018 heatwave could not have happened without climate change. Unless the world drastically reduces its use of oil, gas and coal, the impacts of human-caused climate change will continue to worsen."

More than 400 previous extreme-weather attribution studies have looked at the extent to which climate change made extremes greater or more likely and the methodology used in the report was endorsed by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its Sixth Assessment report.

Other peer-reviewed studies have also calculated the financial damage attributable to climate change in particular extreme events, using the same methodology as in this study, for example a study of Hurricane Harvey, which hit Texas in 2017, found that $67 billion of the damage could be attributed to climate change.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Simon Levey

Communications Division