Imperial researcher in effort to find evidence of habitability on Mars

by Colin Smith

Imperial researcher in latest remote international mission to the red planet.

In the Royal School Mines at Imperial hangs a gargantuan antique framed map of England that is covered in markings and splotches of fading colour.

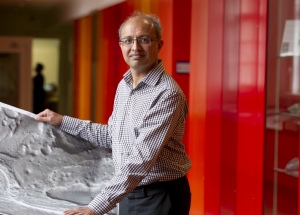

Professor Sanjeev Gupta

Professor Gupta is one of only two UK scientists to take part in the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission. The mission, which will be controlled remotely by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena USA, is expected to touch down on the red planet on 5 August 2012. The $US 2.7 billion operation will involve a team of 200 scientists from around the world who will be assessing whether Mars has had conditions favourable for life. They will also be determining whether conditions were favourable for preserving a record of evidence in the rock about whether life has existed there.

"Earlier Mars landers and rovers examined the Mars surface but didn’t give us the opportunity to study the geology of thick piles of sediments in detail."

– Professor Sanjeev Gupta

Department of Earth Science and Engineering

Professor Gupta says: “Earlier Mars landers and rovers examined the Mars surface but didn’t give us the opportunity to study the geology of thick piles of sediments in detail. Sedimentary rocks are the history books of a planet, preserving information about past environmental conditions. On Earth, they also preserve evidence of past life. This new phase of exploration will enable us to analyse the geology in much more detail, giving us an exciting opportunity to learn more about our nearest neighbour.”

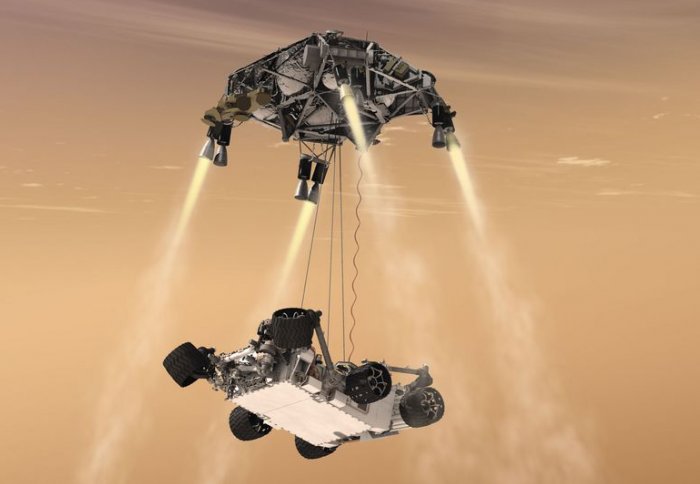

NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory spacecraft is currently travelling through space and in early August, after a 154 million mile journey, the craft will reach Mars’ outer atmosphere at speeds of approximately 13,200 miles per hour. The heat shielded spacecraft will use the atmosphere as a break to slow down initially. At an altitude of seven miles a parachute will be deployed to further slow the descent towards the surface of Mars. As it nears the ground a another craft will be ejected, which will use jet power to stabilise its decent, hovering above a drop zone and carefully winching a mobile six-wheeled, nuclear powered science laboratory – approximately the size of a Mini Cooper – out of its innards and onto the surface. The entire landing procedure is expected to take approximately 10 minutes.

The mobile laboratory, which is equipped with cameras, a robotic arm, and a range of instruments to study the geology and geochemistry of Mars, will land on the floor of Gale Crater. The Crater, located near the planet’s equator, is between 3.5 to 3.8 billion years old, with a 5.5 kilometre high mountain at its centre called Mount Sharp.

“NASA chose Gale Crater as the landing site because it has a number of really exciting geological features that we are hoping to explore. These include a canyon and what appears to be a lake bed on the floor of the Crater, as well as a channel and a delta, which we think may have been carved by water. We will use the rover’s cameras, including one which is like a powerful magnifying glass, to study the geology up close.”

This not the first time that Professor Gupta has studied Martian geology, in January 2009 he studied a set of spectacular satellite images and published a paper in the journal Geology, which suggested that Mars was warm enough to sustain lakes three billion years ago - a period of time that was previously thought to be too cold and arid to sustain water on the surface. The research suggested that during the Hesperian Epoch, approximately three billion years ago, Mars had temporary lakes made of melted ice, each around 20km wide, along parts of the equator.

Professor Gupta adds: “We think that Gale Crater was formed sometime between the early warmer, wetter Noachian Epoch and the colder, drier Hesperian Epoch of Mars’ history, making it a really interesting site to study. The geology and mineralogy of the Crater may help us to piece together the reasons why Mars’s climate changed so dramatically.”

The Mission is planned to last for one Martian year, which is 98 weeks. Professor Gupta will spend part of that time at mission control in the Jet Propulsion Lab. Each day, hundreds of scientists will work together round the clock, analysing data beamed back to mission control, planning experiments and devising the next day’s program for the Rover.

Professor Gupta says: “I am really excited to be working with such a distinguished team in a completely new work environment on such an immense project. If William Smith were alive today I am sure he’d do what us geologists in the team are planning to do – roll up our sleeves and get down to mapping the geology of this crater.”

Professor Gupta’s Mars research is funded by the UK Space Agency and supported by NASA.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Colin Smith

Communications and Public Affairs