Our primitive reflexes may be more sophisticated than they appear, study shows

Supposedly 'primitive' reflexes may involve more sophisticated brain function than previously thought, according to an Imperial College London study.

The vestibular-ocular reflex (or VOR), common to most vertebrates, is what allows us to keep our eyes focused on a fixed point even while our heads are moving. Up until now, scientists had assumed this reflex was controlled by the lower brainstem, which regulates eating, sleeping and other low-level tasks.

Researchers at Imperial’s Division of Brain Sciences conducted tests to examine this reflex in left- and right-handed subjects, revealing that handedness plays a key role in the way it operates. This suggests that higher-level functions in the cortex, which govern handedness, are involved in the control of primitive reflexes such as the VOR.

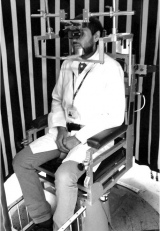

The research, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, involved seating volunteers in a motorised chair which was then spun around at a speed of one revolution every four seconds. This allowed the experimenters to study the VOR by measuring the time it took for the eyes to adjust to the spinning motion. The subjects were then presented with what are known as bistable visual phenomena, optical illusions which appear to flip between two images. Famous examples include the duck which resembles a rabbit, and the cube outline which appears to come out of and go into the page simultaneously.

The research, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, involved seating volunteers in a motorised chair which was then spun around at a speed of one revolution every four seconds. This allowed the experimenters to study the VOR by measuring the time it took for the eyes to adjust to the spinning motion. The subjects were then presented with what are known as bistable visual phenomena, optical illusions which appear to flip between two images. Famous examples include the duck which resembles a rabbit, and the cube outline which appears to come out of and go into the page simultaneously.

Scientists already know that this bistable perception is controlled by a part of the cortex which governs more complex, decision-based tasks. Because of this, researcher Qadeer Arshad and his colleagues did not expect to find any link between the two processes.

They were surprised to find that processing bistable phenomena disrupted people’s ability to stabilise their gaze, following rightward rotation in right handers and leftward rotation in left handers. Arshad said “This is the first time that anything of this kind has been shown. Up until now, the vestibular-ocular reflex was considered a low-level reflex, not even approaching higher-order brain function. Now it seems that this primitive reflex was specialised into the cortex, the part of the brain which governs our sense of direction.”

They were surprised to find that processing bistable phenomena disrupted people’s ability to stabilise their gaze, following rightward rotation in right handers and leftward rotation in left handers. Arshad said “This is the first time that anything of this kind has been shown. Up until now, the vestibular-ocular reflex was considered a low-level reflex, not even approaching higher-order brain function. Now it seems that this primitive reflex was specialised into the cortex, the part of the brain which governs our sense of direction.”

This study could help scientists understand why some people become dizzy through experiencing purely visual stimuli, such as flickering lights or busy supermarket aisles. Professor Adolfo Bronstein, a co-author on the paper, said “Most causes of dizziness start with an inner ear - or vestibular - disorder but this initial phase tends to settle quite rapidly. In some patients, however, dizziness becomes a problematic long term problem and their dizziness becomes visually induced. The experimental set-up we used would be ideally suited to help us understand how visual stimuli could lead to long-term dizziness. In fact, we have already carried out research at Imperial around using complex visual stimuli to treat patients with long-term dizziness”

The research was funded by the UK Medical Research Council.

Reference

Q Arshad et al. 'Handedness-Related Cortical Modulation of the Vestibular-Ocular Reflex' The Journal of Neuroscience, 13 February 2013, 33(7): 3221-3227; doi: 10.1523/âJNEUROSCI.2054

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Press Office

Communications and Public Affairs

- Email: press.office@imperial.ac.uk