Haircare science and solar cells: News from Imperial

Here's a batch of fresh news and announcements from across Imperial.

From an award to celebrate outstanding international female scientists, to a new way to map solar cell movements, here is some quick-read news from across Imperial.

Mapping solar cell movements

Hybrid perovskites are materials that show great promise for devices like photovoltaics, or solar panels, due to their high sunlight-converting performance.

However, there are still unknowns about hybrid perovskites that could reveal new ways to improve performance. The material consists of small, positively charged cations made of organic (carbon-containing) molecules surrounded by ‘cages’ of inorganic molecules. The molecules are not tightly held however, and their movements contribute to the electronic and organic properties of the perovskites.

It was thought that the vibrations of the inorganic molecules primarily controlled these properties, but some researchers suspected the rotations of the organic molecules also played a role. This has been difficult to determine, as the processes are extremely fast, occurring on the order of picoseconds (trillionths of a second).

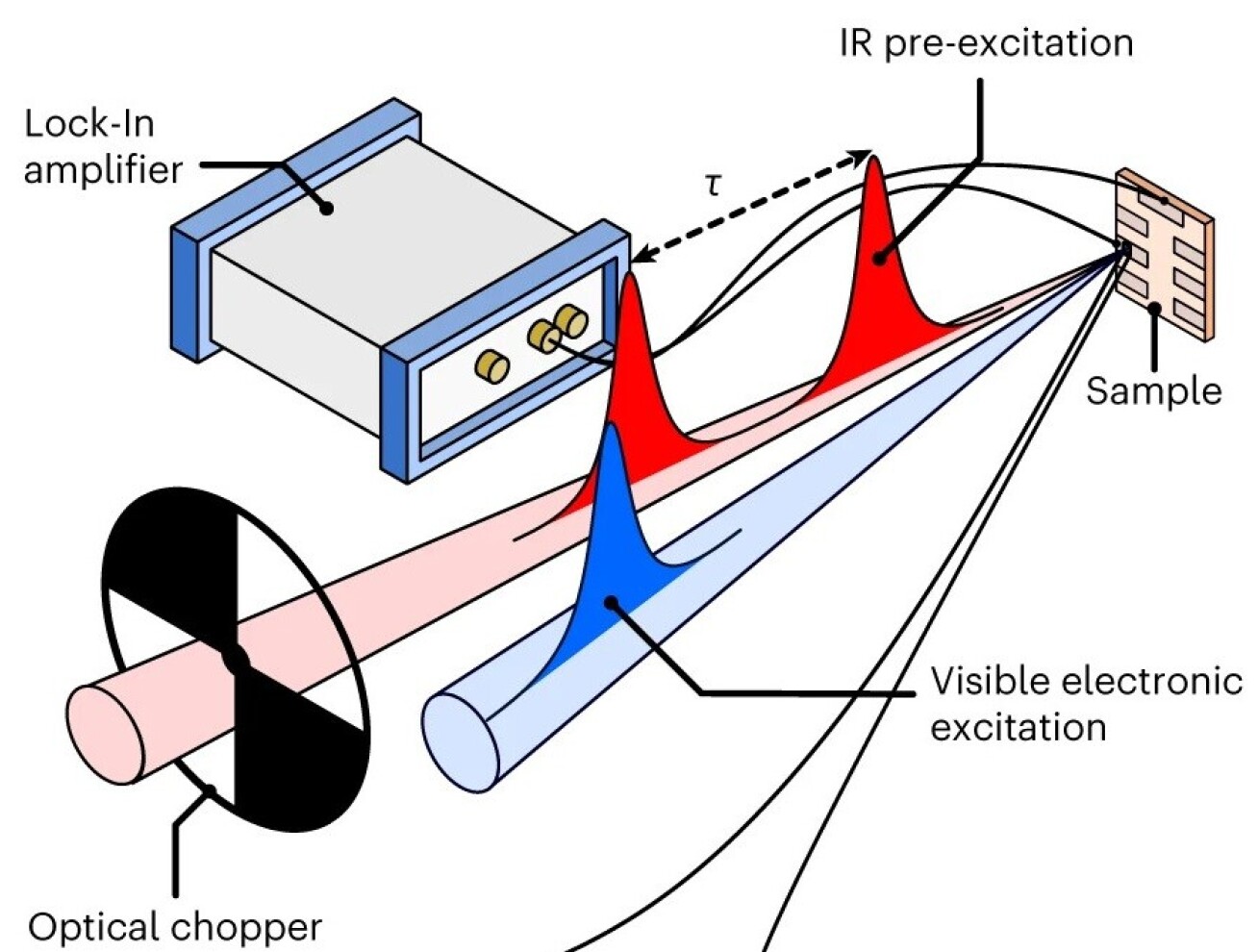

Now, an international team led by Imperial researchers in the Department of Chemistry have devised a technique that can measure these ultrafast movements in working perovskite solar cell devices, which they call ‘Photocurrent Detected Vibrationally Promoted Electronic Resonance’ (PC-VIPER).

With this, they showed that interactions between the organic and inorganic molecules are important for the optical properties of the material and functioning of the devices. Having established this, the team now want to understand the interaction more, such that new designs can take advantage of the process to improve efficiency of functional devices.

Read the full paper in Nature Materials.

Henkel award

Dr Claire Higgins was recently awarded first place in the Martha Schwarzkopf Award for Women in Science, announced at a ceremony in Düsseldorf on 21 November.

The prize, ran by consumer brand manufacturer Henkel, recognises outstanding international female scientists from the life, computer, physical and medical sciences. Dr Higgins was awarded €10,000 and will be mentored by Henkel experts to further translate her research to have patient benefit.

Dr Higgins, from Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, said: “I hope that scientific work like mine will contribute to effective technologies and patented products that can help promote hair growth and reduce skin scarring.”

The award is a tribute to Martha Schwarzkopf – one of the first women to become a managing director in Germany, just two years after women’s suffrage was introduced.

Dr Higgins is also the president of the European Hair Research Society and has been researching human hair follicles and skin since 2003. Her work on hair disease is recognised internationally.

Brain changes in contact sport

Elite contact sports have an array of health benefits, but there are growing concerns that repeated knocks to the head could impact the long-term brain health of players.

New research has uncovered another piece of this complex picture, but the authors say the long-term impacts are still unclear.

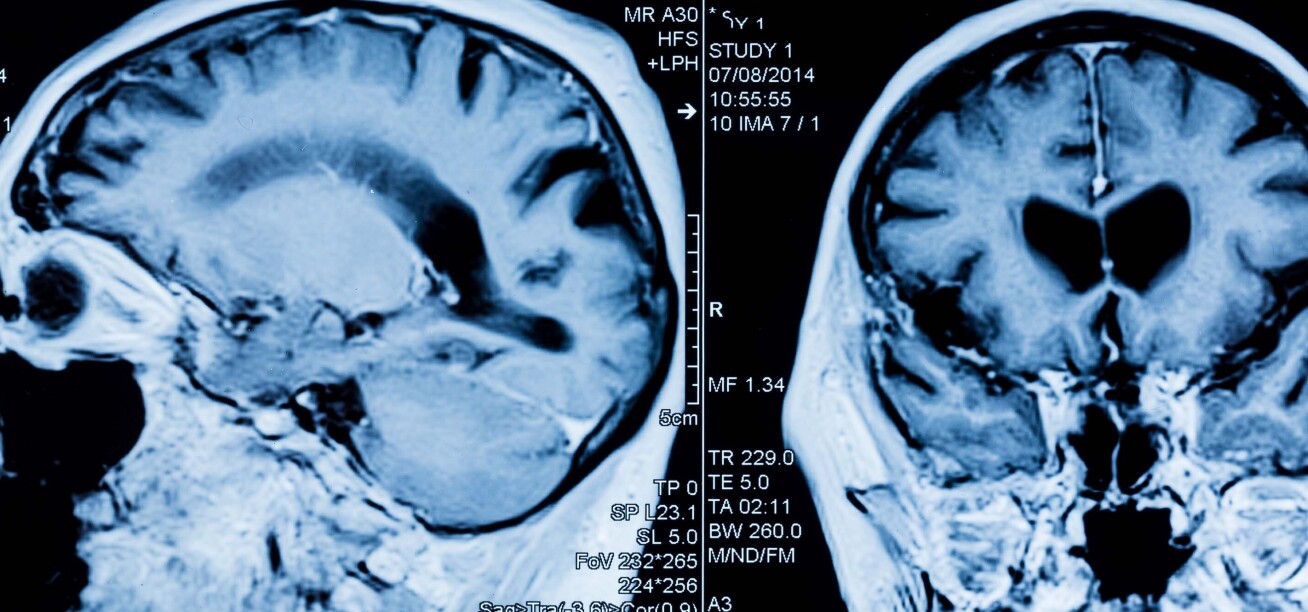

Using data from a study pioneered and funded by The Drake Foundation, researchers in Imperial’s Department of Brain Sciences analysed brain scans of professional rugby players to look for any structural differences, compared to healthy controls of the same age.

They found that elite rugby players had evidence of changes in the cortical grey matter (the outermost layer of the brain) related to both long term rugby participation and recent head injury.

The researchers explain while the analysis shows physical changes linked to head injury, any potential long-term impacts on players’ brain health and function are still unknown. They add that the work highlights the importance of continued research in this area.

Read the full paper in the journal Brain Communications.

Thoracic Society award

Professor Wisia Wedzicha from Imperial’s National Heart and Lung Institute (NHLI) has recently been jointly awarded the British Thoracic Society (BTS) Medal, alongside Professor Peter Calverley at the University of Liverpool.

The medal, which was announced at the BTS 2023 Winter Meeting, is awarded annually to recognise outstanding clinical or scientific contributions to respiratory medicine that have resulted in real benefit to patients and inspiration to peers.

Professor Wedzicha’s work focuses on the causes, mechanisms, impact and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She has a long and distinguished involvement with BTS, notably holding the Editor-in-Chief position for its journal Thorax. The Society said they are “delighted to be able to honour Professor Wedzicha by awarding the BTS Medal for her distinguished career.”

On the award, Professor Wedzicha said: “I am truly honoured to receive the BTS medal and I would like to thank all of the researchers and clinical staff that I have worked with over the years that have helped us all to improve the quality of life of so many COPD patients living with disability.”

Diabetes risk

Researchers found changes in a pancreatic gene increase diabetes risk, but people can manage the condition with a readily available drug.

Type 2 Diabetes is a disease that is estimated to affect 1.3 billion people by 2050. Heritability is 70% in type 2 diabetes risk and several genes have been identified to cause monogenic forms of diabetes with onset in infancy, such as GLIS3 involved in insulin-secreting cell development and function.

Imperial researchers were part of an international team of collaborators who investigated the contribution of rare pathogenic GLIS3 variants to most common forms of type 2 diabetes, with the long term goal of better personalised medicine. The study looked at how GLIS3 was sequenced in 5,471 individuals and identified 105 rare variants that were carried by 395 participants and further investigations were performed to evaluate the impact of these mutations, finding 49 loss of function mutations. A further meta-analysis, combining these results with data obtained in 100K individuals, showed that loss of function GLIS3 mutations double type 2 diabetes risk.

Professor Philippe Froguel, Chair in Genomic Medicine in the Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, said: “We noticed that several patients with type 2 diabetes and GLIS3 mutations were well controlled with sulfonylureas, the oldest (and low cost) oral drug against diabetes which indicates that the genetic diagnosis of T2D with GLIS3 mutation may avoid not necessary and challenging insulin therapy in many patients. This study paves the road towards more personalised diabetic medicine.”

Want to be kept up to date on news at Imperial? Sign up for our free quick-read daily e-newsletter, Imperial Today.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division

Benjie Coleman

Department of Surgery & Cancer

Ryan O'Hare

Communications Division

Bryony Ravate

Communications Division