Designing microbes to remove microplastics pollution

Author Dr Jose Jimenez introducing briefing paper at IMSE event

Imperial researchers propose using microbes and enzymes to remove microplastics from wastewater and sewage before they are turned into fertilizer.

The latest briefing paper published by the Institute for Molecular Science and Engineering (IMSE) explores the journey of microplastics from domestic wastewater to agricultural fields. It describes how tiny particles of plastics can enter the environment, specifically through wastewater. For example, certain types of clothing generate microplastics during laundry which are then collected in urban wastewater. At the wastewater treatment plant, microplastics accumulate and become part of the sewage sludge treated to produce fertilizer.

“Microplastic contamination is completely unregulated. Is there a safe concentration we can have in the environment?” Dr. Jose Jimenez

The report advocates for the creation of new regulations to measure and characterise microplastics so that we can better understand the effects on human health and calculate the maximum concentration deemed to be safe. To prevent microplastics reaching the soil, the authors propose the use of microbes and/or enzymes as part of the wastewater treatment process.

Published on February 2024, the paper was launched at an event open to the public which began with an introduction from one of the authors, Dr Jose Jimenez Zarco, based at the Department of Life Sciences, followed by a panel discussion and a Q&A from the in-person and online audience. Chaired by Mala Rao CBE, from the Department of Primary Care and Public Health, the panel also included Jenni Hughes (U.K. Water Industry Research), Andy Pickford (University of Portsmouth) and Steve Morris (DEFRA).

Download the briefing paper here

The good and bad of plastic durability

Plastic waste had already reached 353 million tonnes in 2019, and as plastic use increases, so too does its accumulation in the environment. Plastics are very versatile materials because they are flexible, lightweight and durable. However, durability also means persistence, taking between 10-10,000 years to degrade.

From laundry to gardening, microplastics journey into soil

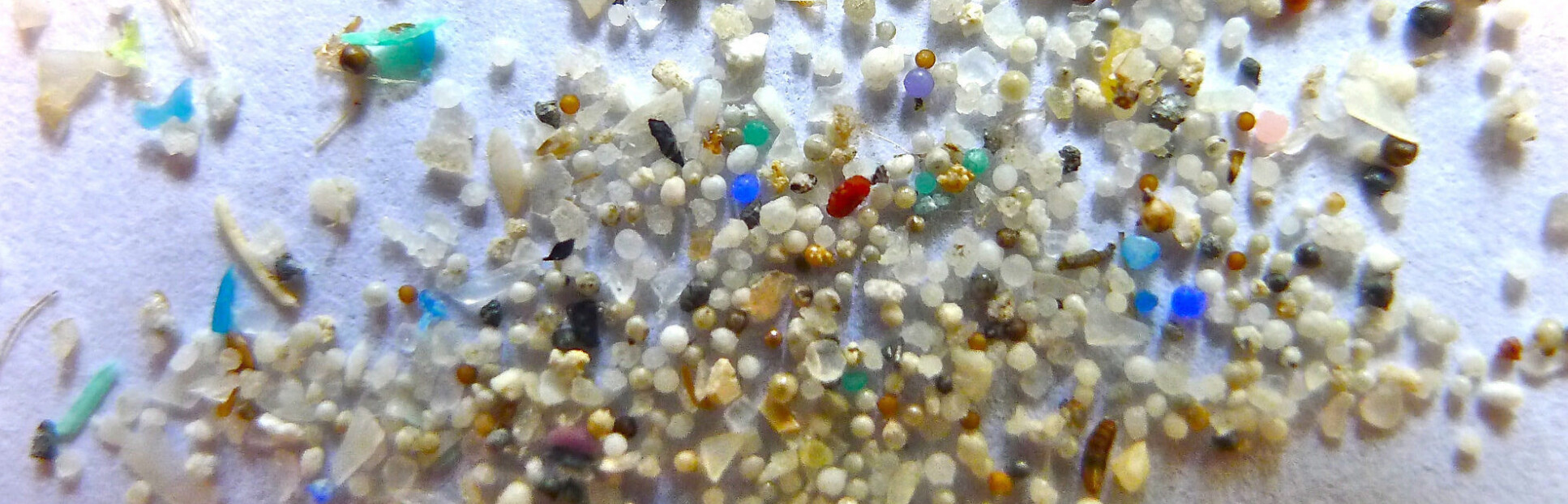

Microplastics are plastics smaller than 5mm in any of their dimensions. Primary microplastics are mainly generated when washing textiles containing polyester or through the wear and tear of tyres on the road. Thus, during laundry or filtering through the street drains after rainfall, microplastics enter the domestic wastewater stream.

“Lots of microplastic pollution comes from urban environment, these microplastics go into wastewater, which is then collected and treated. Solid particles – including human debris – are turned into sludge, which is used to produce fertilizer as it is rich in nutrients, but now also polluted with microplastics”, author Dr Jose Jimenez Zarco summarizes.

Over 90% of U.K. sewage sludge was used in agriculture in 2020, leading to the plastic equivalent of 20,000 bank cards spread onto farmers’ soil per month. Remember plastic durability?. An experiment in Germany showed that land treated with sludge once, 34 years ago, still had a higher concentration of microplastics today than any of the surrounding untreated fields.

Not defined, not regulated

“Microplastic contamination is completely unregulated. Is there a safe concentration we can have in the environment?” asks Dr. Jose Jimenez Zarco. While new evidence suggests ingesting microplastics might produce reproductive and multigenerational effects, there is little research done on the type of microplastics humans are exposed to.

"Having standard ways of measuring microplastics is very important." Professor Andy Pickford

The briefing paper emphasizes the need to characterise and quantify microplastics pollution in wastewater before establishing if any level of contamination is safe. Professor Andy Pickford, from the University of Portsmouth, highlighted this point during the panel discussion: “Having standard ways of measuring microplastics is very important. We need to be consistent in the way we measure the type and quantity to survey different areas in a reliable and reproducible way as well as forwards in time, to see if the problem is getting worse or if our interventions are making a difference”.

What can our interventions be?

When not used as fertilizer, sludge is either landfilled or incinerated, which eliminates all microplastics but also generates significant greenhouse gas emissions. The efforts to prevent microplastics reaching the soil while maintaining the benefits of using sludge as fertilizer should be focused on removal.

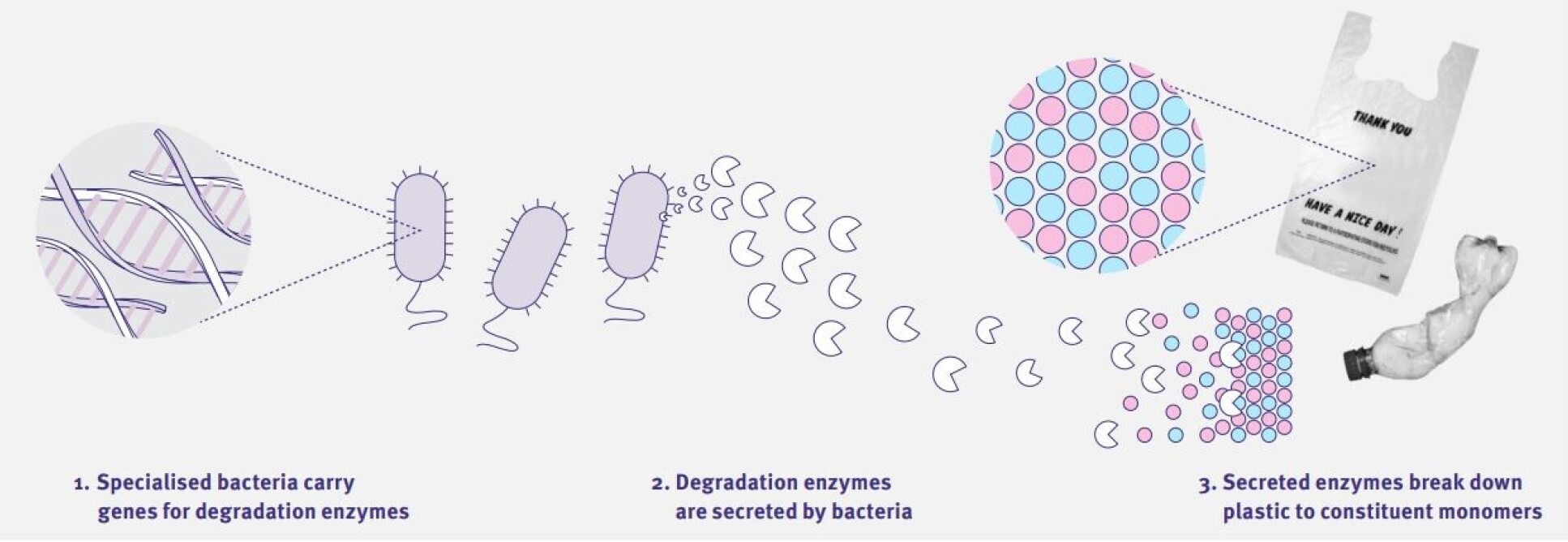

Dr Jimenez Zarco’s research group is researching this topic at the Department of Life Sciences. The briefing paper explains how esterases, a type of enzyme produced by microbes, can break down polyester into environmentally safe molecules that can be used to make polyester once again.

Since other microbes are already present in wastewater plants to produce compost and biogas, the idea would be to use existing infrastructure and incorporate plastic-breaking microbes. Proven to work in the laboratory, research is now shifting towards optimizing the microbes’ survival under the conditions present at a wastewater plant, as well as scaling up enzyme production.

Importantly, while looking at biotech for solutions, authors remind us that minimizing how much microplastic arrives into wastewater to begin with is the first step towards eliminating this type of contamination.

Inter-disciplinary collaboration to address global problems with global solutions.

The Institute for Molecular Science and Engineering was created in 2015 to answer grand challenge questions facing society by combining molecular and engineering research. As Dr Jose Jimenez explains, “Something that Imperial does very well with Institutes like IMSE is to bring together people with different types of expertise that are complementary. For this briefing paper, it is not just the Bioscience team looking at the biotech solution, but we also had civil engineers studying the wastewater treatment process and people from Medicine researching the impact in human health.”

“Something that Imperial does very well with Institutes like IMSE is to bring together people with different types of expertise that are complementary." Dr. Jose Jimenez

Briefing papers are launched in events organized by IMSE and discussed with representatives from Industry, Policy, Academia, and Government agencies.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Elena Corujo Simon

Faculty of Engineering