Overview

In traditional chemistry teaching labs, instruments like UV–visible spectrometers are often treated as “black boxes”, meaning they are widely used but rarely examined in terms of how they actually work. This disconnect can limit students’ ability to think critically about measurements, optimise experimental conditions, or troubleshoot errors. To address this, Kristelle Bougot-Robin, Jack Paget, Stephen C. Atkins and Joshua B. Edel developed a first-year undergraduate Measurement Science practical at Imperial that took a different approach: students were challenged to build their own working spectrometers from scratch.

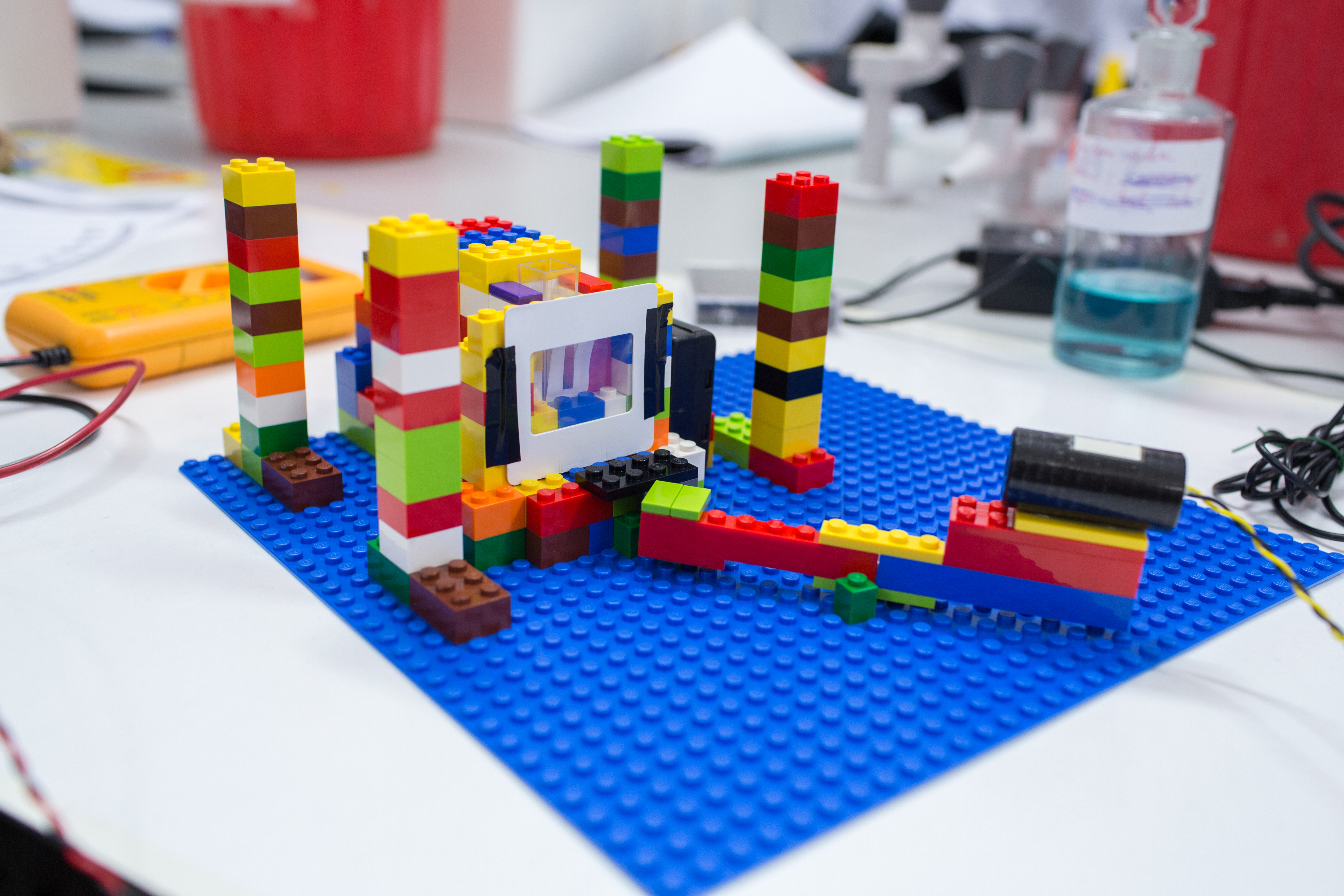

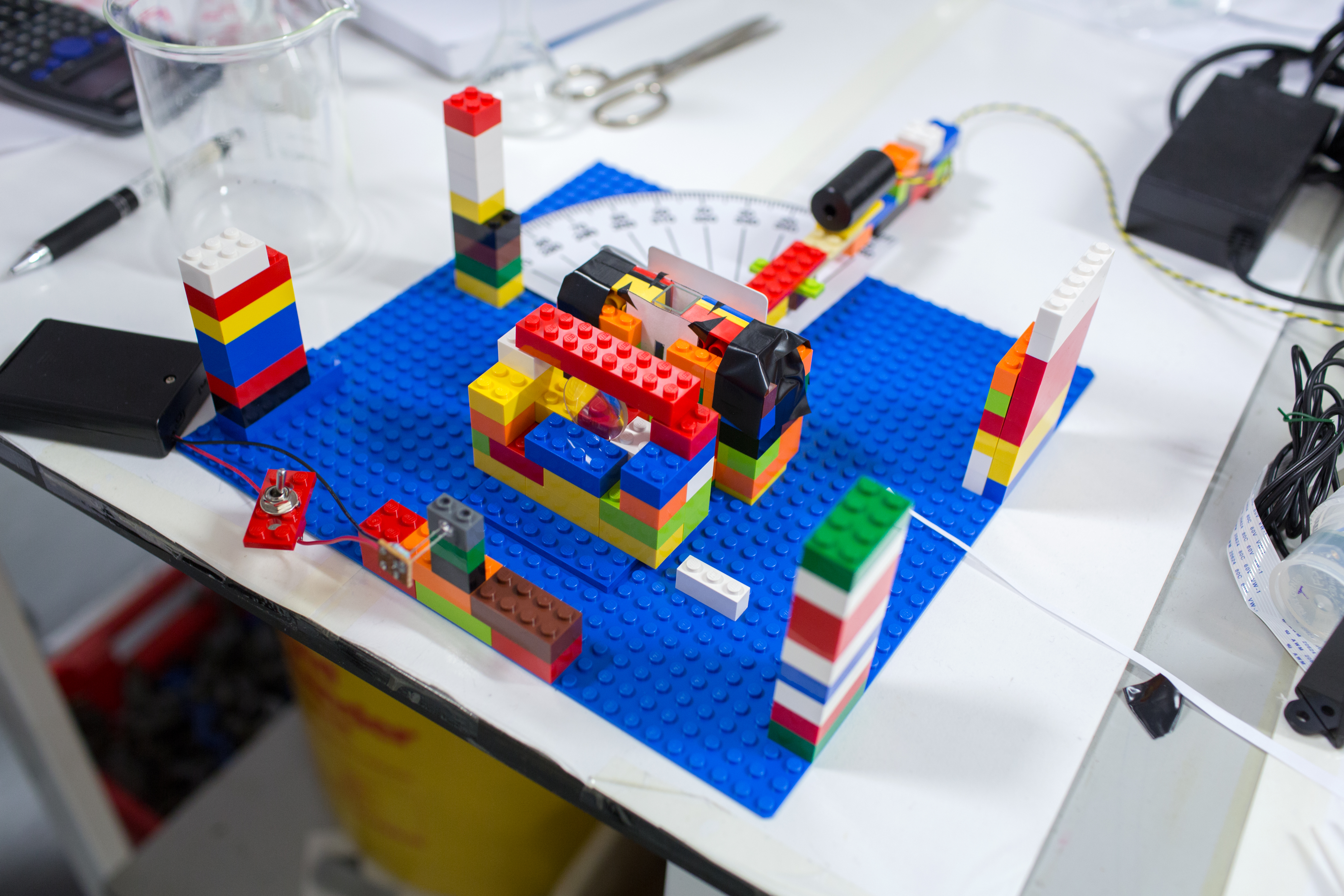

Using simple optical components, a Raspberry Pi microcomputer, and Python programming, and Lego, students designed, built, and operated visible light spectrometers. They then used their creations to conduct real chemical investigations, including calibration studies, absorption spectra, and kinetic experiments, whilst also learning to acquire, visualise, and analyse data using code they wrote themselves.

This project exemplifies how emerging digital technologies, such as low-cost computing, open-source software, and sensor interfacing, can be integrated meaningfully into even early undergraduate chemistry education. It shifted students from passive consumers of technology to active creators, giving them ownership of both their instruments and their learning process.

Context

This project was developed within the Department of Chemistry at Imperial College London as part of a redesigned first-year undergraduate laboratory course. The aim was to move beyond traditional "recipe-style" experiments by offering students a more authentic and interdisciplinary experience of science in practice. Rather than simply following instructions or using commercial instruments, students were encouraged to engage directly with the underlying principles of measurement science.

To achieve this, the lab integrated concepts from physical chemistry, analytical chemistry, and computer programming, using visible absorbance spectroscopy as the unifying theme. Students worked in teams to design and construct their own spectrometers using low-cost components and a Raspberry Pi computer, before conducting experiments and analysing the results through Python scripting.

Digital Technologies in Action

A key feature of this project was the integration of accessible, low-cost digital technologies that encouraged students to move from passive users to active developers. The spectrometers were powered by Raspberry Pi microcomputers, with data collected via photodiodes and analogue-to-digital converters, and analysed using Python. These tools were not pre-packaged or hidden behind graphical interfaces; students were responsible for wiring, programming (from code templates), and calibrating their instruments themselves.

This hands-on use of technology meant that students developed real, transferable skills. They learned to write and modify Python scripts for data capture and visualisation, interface sensors and electronics, and carry out analytical tasks such as linear regression, calibration curve fitting, and error analysis. Importantly, they came to understand not just how a UV-Vis spectrometer works, but why it’s the varied components matter in it’s operation, from slit width to detector placement, and how digital control affects measurement quality.

Evidence of impact came through the data itself. Students produced calibration curves with micromolar sensitivity, assessed instrumental linearity, and even completed kinetic studies of methylene blue reduction. Reports were generated entirely on the Raspberry Pi using LaTeX graphical editor LyX, reinforcing digital fluency from start to finish. This integration of chemistry, programming, and electronics provided a model of data-driven, interdisciplinary learning that reflects the tools and mindset required in modern science.

Pedagogical Impact

The pedagogical shift in this course was deliberate. Instead of following fixed protocols, students were given broad objectives and the freedom to explore solutions, a move away from traditional “recipe-book” labs. The open-ended nature of the activity required them to think critically, troubleshoot independently, and work collaboratively to achieve reliable experimental results.

This freedom fostered a sense of ownership and creativity. While some students pursued minimal viable builds, others took pride in ambitious or even whimsical (yet functional) designs, including elaborate spectrometer housings inspired by architectural landmarks such as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. This variation highlighted how students engaged enthusiastically with the task.

Beyond technical chemistry knowledge, students continued to develop a suite of broader skills: teamwork, time management, digital literacy, and scientific communication. The final reports, written in-session, demonstrated not just an understanding of spectroscopy, but thoughtful reflection on error sources, data integrity, and instrument limitations. These outputs revealed a level of sophistication more typical of later-stage study, highlighting the power of early, interdisciplinary immersion.

Lego Spectrometer 10 years on

The laboratory project design outlined above, and described by Bougot-Robin et al, was implemented as part of the 1st year undergraduate curriculum at Imperial College in the academic year 2014-2015. This activity has evolved since its implementation and has been part of the curriculum to this day with some adaptations. The two main changes relate to an effort to reduce the cognitive overload in the experiment related to the access to technology, and focus the activity on the spectrometer design aspects and the data analysis itself.

The first change consisted in moving away from the use of the Raspberry Pi computer to instead connecting the photodiode and associted electronic directly to a Windows PC. While this change removed an emblematic piece of technology and student exposure to low-cost computing platforms, it benefited overall student agency. The use of Raspberry Pi implied the use of the Linux operating system which the majority of students never interacted with before, creating unnecessary barriers to simple tasks like file handling and searching, application launching or access to familiar word processing applications for report writing. And while these are simple tasks that can be learned, it created stumbling blocks that affected student confidence and shifted focus from the more important aspects of the experiment.

The second change relates to the use of Jupyter notebook technology for the data acquisition and analysis. The original experiment design made use of individual Python script templates that were run from a command line interface. Such a choice, partly related to the use of the Raspberry Pi platform, had the advantage of computational simplicity, but the use of the command line interface (unfamiliar to most students) created accessibility barriers. Also importantly, the implementation of the Lego Spectrometer laboratory project was linked with the parallel introduction of a series of workshops that introduced Python as a tool for data analysis and visualisation, with students applying the techniques learned in these workshops to analyse the data acquired with their own built spectroscope. While the Python for Data Analysis workshops used the Jupyter notebook interface (previously called IPython notebooks) for accessibility reasons, the use of stand alone Python scripts in the Lego Spectrometer project created a cognitive disconnect which made it difficult for students to recognise the context in which they were asked to apply their knowledge. The shift to use Jupyter notebooks eliminated this barrier by the use of the same technological platform in both contexts, while also allowing for a more integrated approach to data analysis combining data acquisition, Python code, plots as well as verbal analysis and annotations in a single document.

With these changes, the Lego Spectrometer laboratory project continues to be an integral part of our 1st year laboratory curriculum, embodying a self-driven demystification of laboratory techniques and instruments and interaction with technology. In the words of Alex Ivanov who developed and supervised the experiment during the first years after its introduction:

At the Department of Chemistry, I have seen how hands-on projects, even built with something as simple as Lego blocks, can spark incredible enthusiasm, teamwork, and creative problem-solving. This spectrometer project is one of the best examples I have come across. By building their own instruments, students are not just learning how spectroscopy works – they are taking ownership of the process, experimenting, and discovering together. It is the kind of experience that sticks with them, builds confidence, and shows just how exciting science can be.

Acknowledgements and References:

The authors would like to thank Kristelle Bougot-Robin, Jack Paget, Stephen C. Atkins and Joshua B. Edel for their vision and work in developing the original Lego Spectrometer project. We are also grateful to those who generously shared their time, insights, and space during this project – in particular Dr Alex Ivanov and Dr Francesco Aprile – whose perspectives helped shape this reflection.

Publications

K. Bougot-Robin, J. Paget, S. C. Atkins and J. B. Edel, J. Chem. Educ., 2016, 93, 1232–1240. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b01006

In the media

https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/163933/imperial-students-bring-play-into-with/

https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8871819/lego-spectrometer-lab-in-a-box

https://www.raspberrypi.com/news/lego-spectrometers/

https://theanalyticalscientist.com/issues/2015/articles/mar/the-lego-lytical-scientist/