Overview

One of the first steps for any research project is the Funding Proposal and the accompanying financial feasibility work.

This resource is designed to give an overview of Imperial’s policies on Research Project Costing, how to draft a Funding Proposal, and how to draft a Budget.

Costing & Full Economic Costing

It is Imperial’s policy to calculate the Full Economic Costing (FEC) of all research proposals, regardless of funder. This is a mandatory process for research conducted at Imperial, in line with the Government Transparency Review (1998) and subsequent Transparent Approach to Costing (TRAC) utilised by all Higher Education Institutions in the UK.

A particularly valuable resource is Imperial’s FEC Charge Out List, which gives all the details of services available to your project at Imperial and how much they will cost.

The Imperial Costings webpage has some excellent guidance on what is covered by FEC, how it’s calculated, and has great information on sub-items such as Full-Time Equivalent (FTE).

Download the PDF of this resource to check the Further Reading & Resources page for links to the Imperial website for this topic, Imperial’s “Costing & Pricing of Externally Funded Research” Policy, and for a copy of the FEC Charge Out List. The PDF copy of this resource also includes a full list of contacts for costing queries, organised by Faculty. For direct, project-specific, pre-award support with costing, you will need to reach out to the appropriate team for your faculty.

How to write a Funding Proposal

First Steps

Many proposals will primarily be for funding applications, so the first place to look for information is the guidance provided by the funding body or council for applications. This guidance should include what they expect to see, including word count estimates, and information on what a successful application looks like. This may vary between organisations.

The other main purpose of research proposals is for ethics submissions. If the proposal is for an ethics submission, you should refer to any guidance provided by the REC, or within submissions systems such as IRAS.

Be sure to refer to the guidance as some bodies have very specific requirements for submissions. One example of this is the UKRI’s Je-S system, which specifies font, point size, margin sizes, and table / image requirements amongst other items. Proposals that do not adhere to any provided guidance will usually not be considered.

How to write a Funding Proposal

- 01. Plain English Summary

- 02. Introduction & Background

- 03. The Intervention

- 04. Objectives & Research Questions

- 05. Study Information

- 06. Proposed Sample

- 07. Data Collection & Methodology

- 08. Site Information

- 09. Study Specific Procedures

- 10. Data Analysis Plan

- 11. Ethical Concerns & Considerations

- 12. Budget & Costings Breakdown

- 13. Impact Statement

- 14. References

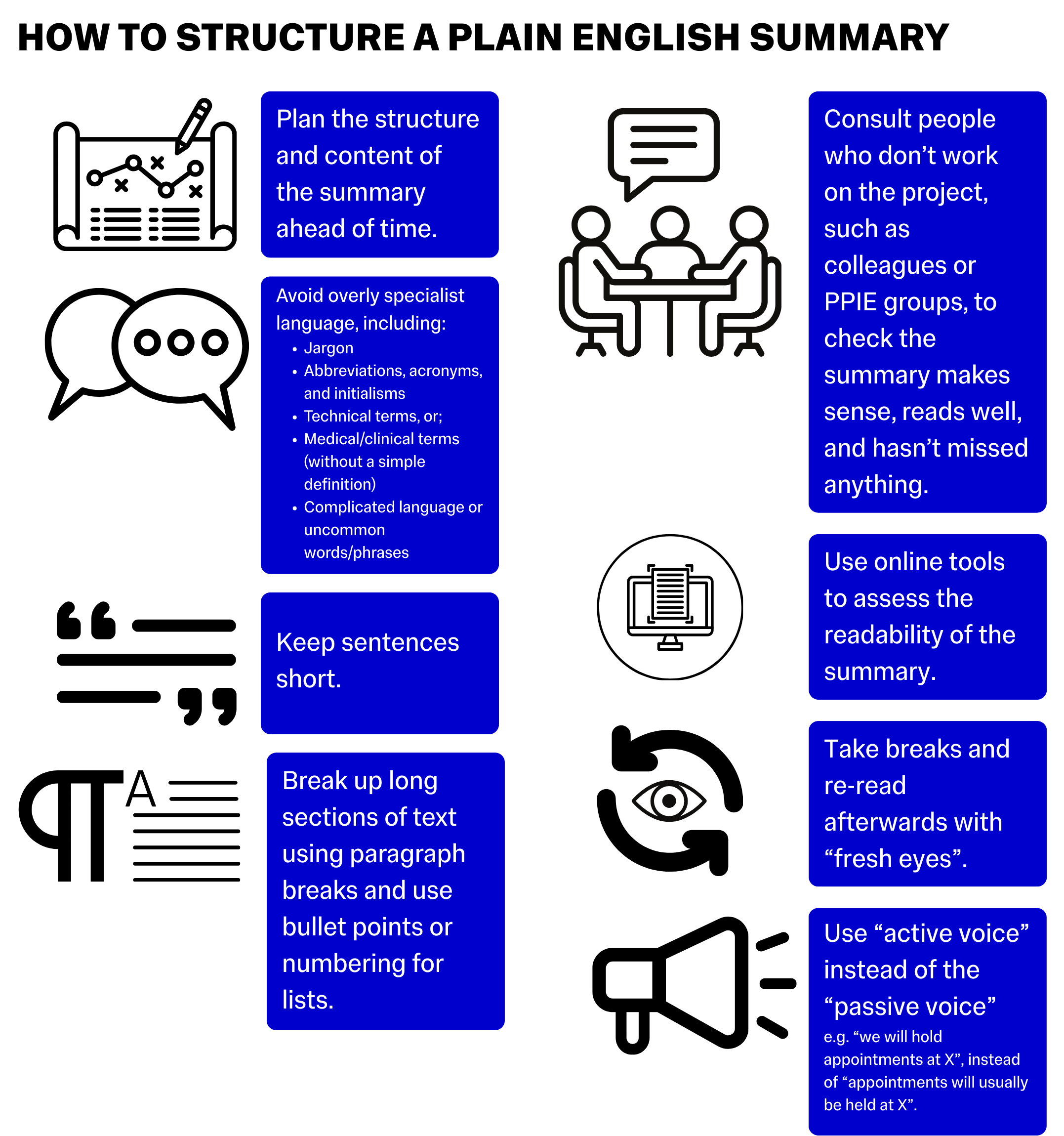

A Plain English Summary (PES) is usually the first section of a funding application, and sometimes academic papers (though it should be noted that a PES is not the same as an abstract).

The purpose of a PES is to, in a short format, communicate the nature and purpose of a research project or study, in plain language, devoid of jargon or complex terms.

A good PES should accurately and concisely describe the project, but should be easily understood by any reader, including a lay person. It should also be able to stand alone and should be both understandable and complete without further information or reading.

The Value of Plain English Summaries

When communicating information about your project to potential participants, you will usually be speaking with lay persons, who don’t necessarily work in science, medicine or research, but who will still need to understand the project, and what it involves, just as well as the study team. A big part of this is that prospective participants must fully understand what their participation will involve, what the risks are, and what will happen to their data and any donated tissues or samples.

You can write a PES to accompany your Participant Information Sheets (PIS) and for your Informed Consent Forms (ICF).

What to include in a Plain English Summary

In your summary, consider including:

- Background:

- What question or problem does your project look at?

- What impact does this problem have on people/patients and services like the NHS?

- Aims:

- What question does your project aim to answer?

- Specific objectives

- Research Plan:

- How do you plan to answer the question?

- What methods will you be using?

- What is the general structure of the project?

- Community Outreach:

- How has your project been shaped and influenced by people with lived experience from the community you plan to study?

- How will these groups continue to influence and have input on the project?

- Dissemination:

- How, where, and when will the work be published?

The introduction or background section of a proposal should include the existing literature on the topic of study being proposed, and the scientific grounding for the proposal.

Where there is little existing literature, for example for projects involving novel technologies, you must be able to demonstrate proof of concept, and should ideally be able to demonstrate where the novel technology or intervention fits into the current landscape i.e. what niche does this innovation fulfil?

You should clearly describe the planned intervention e.g. testing the use of a new medical device, and how you intend to use the intervention within the study.

You should clearly state the aims of the project, and what research question the project aims to answer. You will usually format this as a bullet point list.

This may include a statement of what knowledge gap this project aims to address.

This is where you should state the study specific information such as:

- Study type

- Study duration

- Methodology type

- Sample size, and any relevant demographic information

If you are unsure of what study type your project is, the downloadable PDF of this resource includes a brief list of the most common study types.

The size of your sample will be dictated by the power calculation conducted by your study statistician or data analyst. This calculation will give you the minimum number of participants required to observe a significant correlation between the variables. The term “power” or “statistical power” specifically refers to the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis.

When deciding sample size, it is important to consider how the sample size may change across the course of the trial. Participants may drop out, or may be withdrawn for other reasons, leading to a smaller than planned sample size. To circumvent this issue, it is recommended define the endpoint of recruitment i.e. when recruitment closes, as the number of participants who reach a specific point in the study.

For example, in a study of 100 participants recovering from kidney transplants where each participant attends five appointments, and the primary hypothesis assesses participant outcomes at visit three (with a secondary hypothesis assessing outcomes at visit five), instead of ending recruitment when 100 participants have been screened for enrolment, it would be sensible to end recruitment when 100 participants have attended their third visit. This ensures that the minimum sample size for statistical power has been achieved, and any additional participants over that number will only strengthen the data set.

It should be noted that, this method can incur significant additional financial burdens on your budget (as you will be screening and enrolling a higher number of participants).

In terms of demographic distribution of participants, you should ideally not restrict the sample to certain demographic factors, unless they are relevant to the research question.

For example, a study that aims to assess maternity outcomes in ethnic minority patients would be limited to female participants overall and then may be ethnically split into two groups: one group of patients from ethnic minority groups, and a control group of patients from majority ethnicities. However, if the study was assessing how patients at high risk of strokes respond to treatment using warfarin, there would be no need to stratify the groups by demographic factors as they are not relevant to the hypotheses.

You may still observe some demographic biases depending on the field of study however.

For example, studies of type 2 diabetes may naturally have a higher average participant age (in years) due to the national average age at which type 2 diabetes is diagnosed. When drafting your proposal’s sample outline, it can be useful to acknowledge any expected biases.

When writing your proposal, you should include a succinct statement that describes your planned sample, and contains the sample information in as much detail as possible, for example:

“This study will recruit (number) participants. Group A will include (number) participants with (characteristic), and Group B will include (number) participants with no history of (characteristic) as a control.”

OR

“This study will recruit (number) participants from (demographic group / background). Group A will include (number) participants with (characteristic), and Group B will include (number) participants with no history of (characteristic) as a control.”

etc.

It is also important to include some information on how you plan to allocate participants to groups, specifically detailing if there will be any blinding, and any randomisation of participants to groups, how those processes will be achieved, and how researcher bias will be mitigated.

N.B. Your study documents, specifically the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) / Manual of Procedures (MOP), will include more detailed information about inclusion and exclusion criteria. Detailed criteria are not usually required for proposals.

This section will vary depending on the type of study or trial being conducted, as the type of data and the methods of collection will differ between studies.

Include details on how, from whom, and in what format you intend to collect your data. For example, a physical examination may be conducted by a qualified Nurse, who will record the participant’s height, weight, blood pressure, and demographic data in a standardised case report form. The case report form may be digitised by the Nurse and validated by another member of the project team. Tailor this section to your specific project and provide enough detail that readers can easily understand your planned methodology.

You should also include some information on how data will be stored, and how it will be collated for analysis, you should also provide some information on how data will be validated (i.e. confirmed to be accurate), and any information on how data will be securely transferred between parties (e.g. from the site to your statistician etc). This will demonstrate to anyone reviewing your proposal that you understand data protection and data integrity, and that you understand both why you need the data you are collecting, how to utilise the data properly in a research context.

At the proposal stage of planning a study / clinical trial, it is unlikely that you will have officially secured the research site, as this would likely be dependent on funding. You can indicate the proposed sites, but state that these will be confirmed later in the process.

You should, at this point, include a small amount of information regarding why you would choose the proposed site e.g. the site is geographically appropriate, perhaps there is a specific clinic there that will be part of the recruitment process, maybe your team has an established relationship with a clinic there, or perhaps there are specific laboratories there that will be needed for sample processing etc.

Alternatively, you may be able omit this section if you do not have a proposed site – Check any funder specific guidance that is available.

This section can include site specific details where it is possible to do so, for example, you could state that the site has in-house secure data or sample storage facilities that you would be able to use as part of the study.

Where you do not yet have any site-specific information, you should include details of the proposed plans for sample or data storage, and demonstrate how you plan to meet data protection, security, and participant confidentiality requirements.

Where you have study specific procedures such as phlebotomy, or any intervention specific procedures (e.g. administration of an IMP) etc. you should detail them here.

This will be drawn up in close collaboration with your study statistician, or equivalent. This will lay out the plan for how the data generated by the study will be analysed and may dictate how data will be presented to answer the research questions.

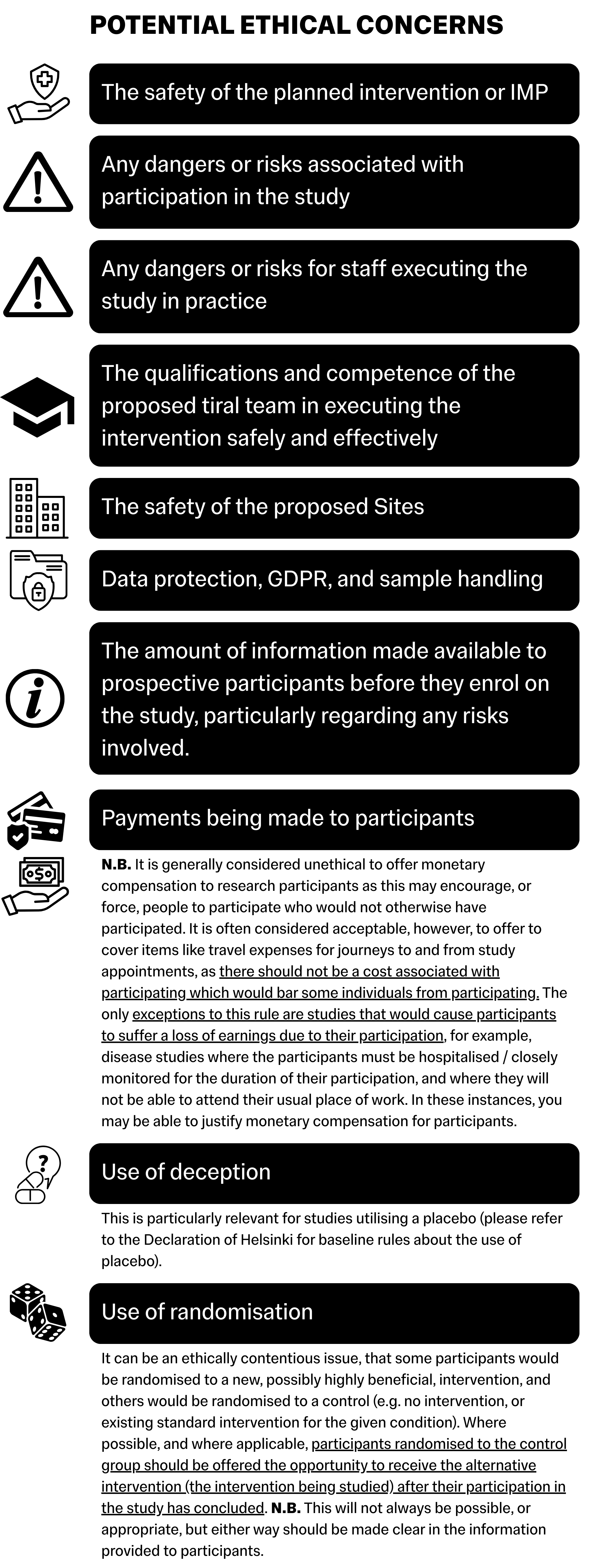

If there are any ethical considerations at all, including on the choice to use, for example, human participants, you should detail how the study is ethically sound, and how any ethical concerns will be managed or mitigated in practice. Proposals that raise significant ethical concerns, or where there is no clear plan to mitigate ethical concerns, will not be considered by funding bodies, and would not pass a research ethics committee assessment.

You should fully consider any ethical issues that risk occurring as part of the study, and should demonstrate your understanding of these risks, and most importantly how they will be prevented or mitigated in practice.

It should be noted that some ethical concerns are never acceptable and cannot be sufficiently mitigated. The main items that may reach this threshold relate to participant safety and the safety of any proposed intervention, up to and including risk to life. In these instances, the project should go through other trial pathways such as cadaveric studies or animal studies before a proposing a clinical trial involving human participants.

See below for a non-exhaustive list of potential ethical concerns to consider:

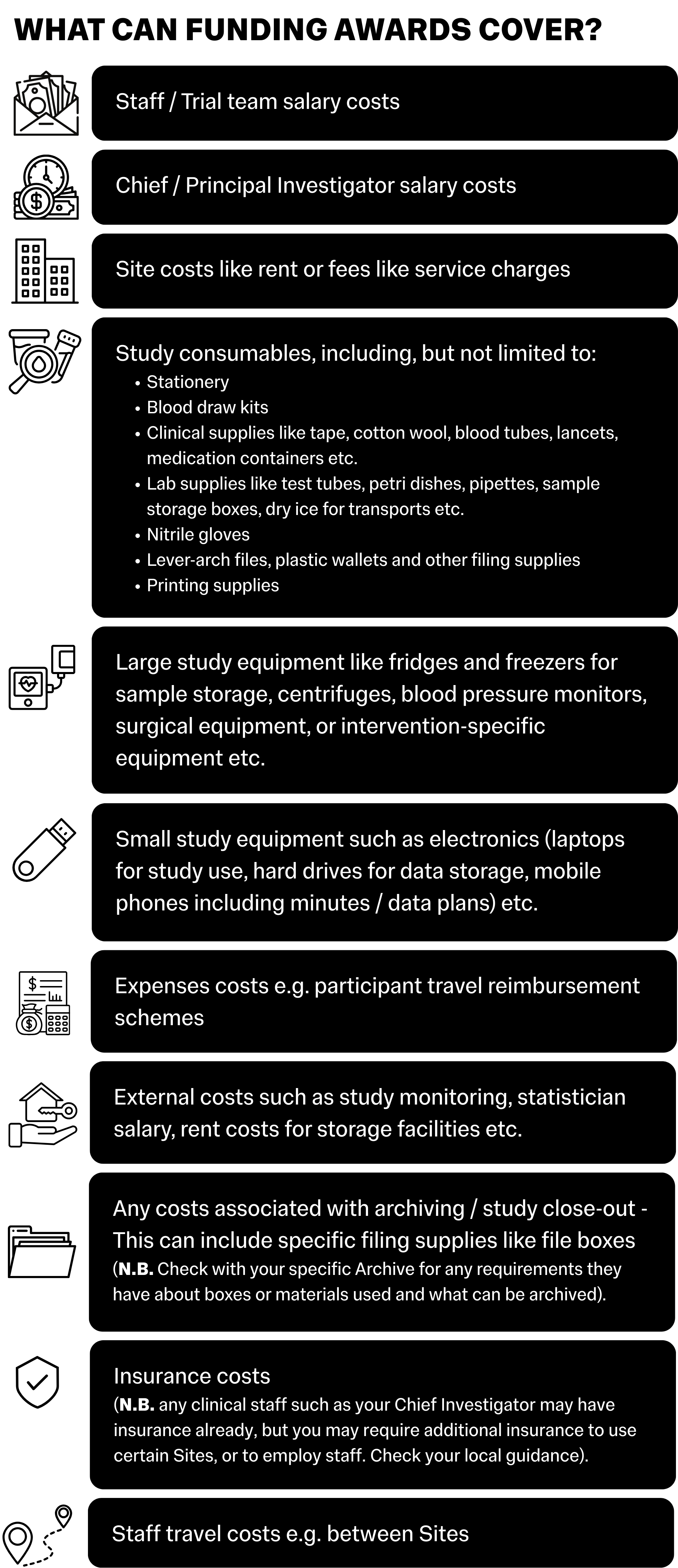

When including information on a proposed budget within a research or funding proposal, you should first take note of any provided guidance on how to present this information and what to include.

The budget items to include will vary between funding bodies, as will the items a funding body can / will cover as part of an award. For example, some funding bodies can cover all costs associated with a trial, whereas other funding bodies may only cover study consumables and site costs but not staffing costs. Another useful item to note is the overall award amount, and how many projects the funding body intends to fund out of that amount. If your proposed budget exceeds the total award amount or would account for a large portion of an award designed to fund multiple projects, you will be less likely to be successful.

How to present the information will also vary. Some funding bodies have pre-set / predefined forms to complete, whereas others prefer you submit a budget sheet as an additional document. Check the guidance for any specifics about table formats, fonts, and other presentation methods.

It is also recommended to calculate “per participant / patient costs” and “per appointment costs” as part of your budget. This means calculating how much it will cost to have each participant move through the study e.g. staff hours cost per participant, consumables used, time spent at the site (rent, staff costs etc.), and calculating how much it will cost per study appointment respectively. These should be separate breakdowns and should be separate from the overall master budget calculations (though should still be kept within the same document). It is a good idea to keep a Budget Master File that includes the full prospective budget, and all breakdowns and itemised lists. You can then easily pull out and collate information relevant to specific funding calls or submissions.

This section should aim to answer the question: “Who cares?” Impact statements are your chance to comment on why your project is important.

This section will help the reviewers understand the value of the proposed project. This should include a discussion on how answering the research question will benefit the wider human population or the field of study and should demonstrate an understanding of how to maximise the impact of the project’s results.

- Check the funder or ethics guidelines and guidance for any restrictions or requirements for how references should be presented, for example if you are expected to reference in a particular style.

- On average, you should usually be using one reference per 100 words, though this may vary depending on the statement you are making or the section you are working in. Most of your references will be contained within the introduction / background / literature section of your proposal, but you may have some references in sections dedicated to methodology and statistical analysis.

- References should primarily come from academic journals and peer reviewed literature. Occasionally there may be necessity to use other sources for reference material, for example reference books or tools (such as the British National Formulary (BNF)), websites, media outlets or specific media reports, or legislation. When referencing sources that are not journals / articles, make sure you follow any referencing style guidance that may apply, for example, if the proposal must use APA referencing style, make sure all of your sources are referenced in this style.

- It is good practice to use superscript numbers in the text to indicate a reference, and to make sure that the number in the text (e.g. “journal quote” 1 ) corresponds to the list number of that reference (so in this example, the reference would be number 1 in the references list). Additionally, references should be organised in the order they first appear / are referenced in the text.

N. B. Some funders / ethics guidelines will require the reference to be named within the text. In these cases, you should use the “Name (Date)” format of in-text referencing, and the references list should be organised in the order each reference first appears in the text. Refer to any specific guidance provided, as needed.

General Guidance for Proposals

- Study the proposed funding source. Thoroughly read, and follow, any provided guidance or direction for the content and style of applications. If in doubt, funding bodies do usually provide a point of contact for queries so always ask if you are unsure of a process or the meaning of a guideline etc.

- Consider the appropriateness of the funding source before making an application. For example, if the funder primarily accepts business-related applications, and your project is focused on the efficacy of a new pharmaceutical available on the NHS, it would be a good idea to reconsider your application to that specific funding body.

- Carefully check guidance provided on what resources a funding body will be able to cover. This will vary between funding bodies.

- Ensure you can demonstrate a good understanding of:

- The scientific background of the project, and the reasons for undertaking the project.

- The regulatory requirements for the project, including an understanding of ethics.

- The project specific processes and requirements.

- The planned methodology, including planned analyses.

- The proposed budget and reasons for the amounts requested for funding.

How to Draft a Budget

What items to cover?

From people to places to consumables!

The funding body you are applying to will provide detailed information on what they plan to cover as part of an award, and any funding limits they intend to impose. Funding limits can include the full award total, how many projects they intend to fund from that amount, and the maximum award amount per project.

The items that a funding body will cover will vary between funders and between awards, so you should check their guidance and ensure you have a plan on how to cover any items that the funder will not pay for. This may mean a second source of funding.

The graphic below is a non-exhaustive list of the main items covered by funding awards:

Funding Limitations

What not to include

What is able to be covered as part of a grant or funding award will differ between funding bodies. As mentioned above, you should check the information provided by the funding body, and tailor or reconsider your proposal accordingly.

When proposing a budget, you must be able to justify the cost of staff salaries, study equipment and consumables and demonstrate that you have estimated reasonable price points for items (particularly for consumables and equipment). If you are requesting a large amount of money, but you cannot justify the costs you’ve calculated, you will not be successful. Some exceptions may be made for costs relating to unique equipment (e.g. equipment required for the study that is only produced by one company in the world), but you must be able to demonstrate that this is the case.

It is also important to ensure your proposed budget only includes items the funder can / will fund. Not only does this give the reviewers an idea of how much your project will cost them specifically, but it also demonstrates that you have read and understood the guidance provided. Where the funder will not be able to cover all of your project costs, you should have a secondary funding plan to cover the remaining items, and you should detail this within your proposal. This will demonstrate that you have thoroughly thought through and understood your funding pathways. Some funders will allow an additional breakdown of costs they won’t be covering, but that you will have covered by another source – check the specific guidance for further information.

Where applicable, you should also check your proposed budget against the overall award plans. If the funder intends to award a total of £1M split between 10 projects, and your project is proposed to cost £900K, it is highly unlikely that you would be successful.

Pricing Equipment & Consumables

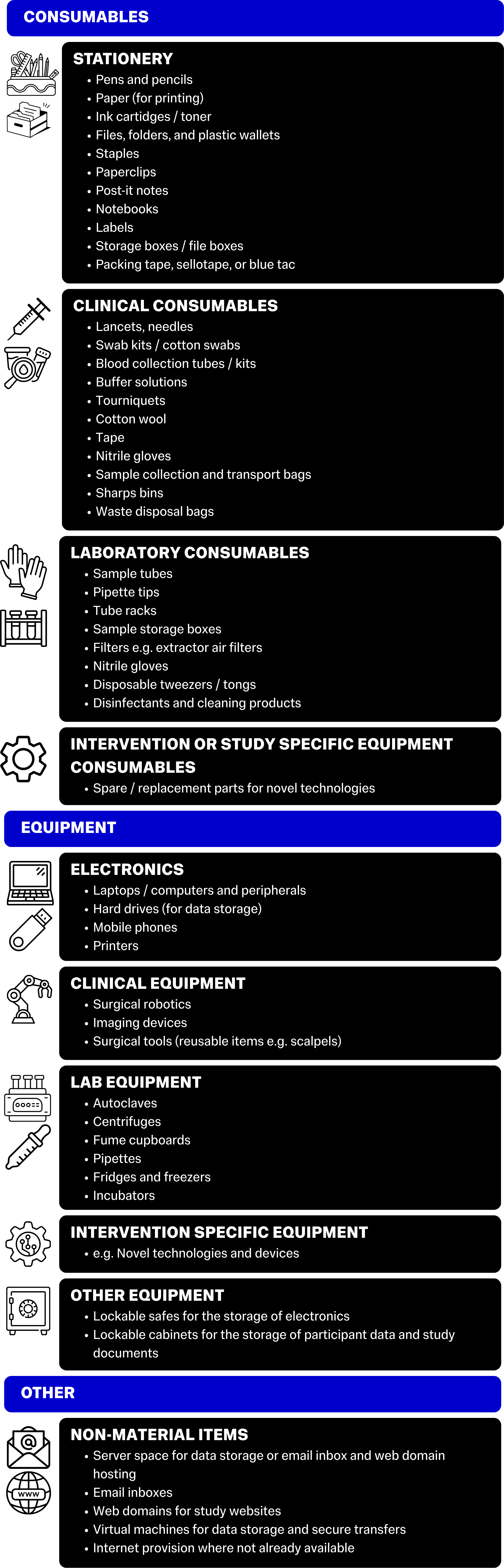

It is a good idea to start by simply drafting a list of everything you will need to execute your project, from the larger equipment and resources, all the way down to each item needed for a participant’s appointment.

Consumables refers to all items necessary for the trial to function that are single use, or are parts for equipment that will need to be regularly replaced.

Equipment refers to larger items and technologies that you will need to complete your project. These items will be multi-use, and you will likely only need to purchase one of each item for the duration of the project.

There may also be non-material items such as servers for email inboxes, or virtual machines for data processing and secure data sharing internationally, that do not have a physical component but will still have a financial cost associated with them.

See the graphic below for some examples of items in each of these categories:

When creating your budget, it’s important to investigate what you will need to purchase, and what will be available to you already. For example, if your primary site is a major hospital, you may be able to use their blood testing service to have participant bloods analysed, rather than purchasing all the necessary equipment and hiring a separate lab space. If your project is being completed at a University or hospital, there are likely printing services in place that you can use, so you might not need to purchase a printer and lots of ink or paper. The first steps of a budget are to research your existing resources, and resources that will become available when you hire your study sites.

The next step is to calculate estimates for the items you will need, including how many of an item you will need across the duration of a study, and the average cost per item.

To calculate how many of an item you will need, you can base your estimates on how many items each patient will use / cause to be used across the course of their participation, and then multiply that by the planned sample size. For example, if each participant has one blood vial drawn at each appointment, and they will have 5 appointments, that should be 5 vials per participant total. If you have a planned sample size of 100 participants, you would need to plan for 500 vials. For many items that don’t directly relate to participants, such as stationery items or items whose usage rate may vary, like waste disposal bags, you should use your best judgement – Don’t forget you must be able to justify the financial amount you are requesting, so don’t guess, instead try to calculate reasonable estimates.

When researching purchasing options to find average prices, you should try to look up the item or equipment from at least three different companies / suppliers. This won’t always be possible, as some items may be particularly niche, or so specific that only one company produces them – In these instances you should clearly indicate if that is the case.

For more common items, document the three suppliers, cost per unit, number of items per unit (or price per item where applicable / available), the date that information was found, and calculate the average cost. You can keep this information in a separate spreadsheet and only include the average proposed cost within the actual budget sheet, but you should refer to this process in your budget justification.

How to price People and Places

Staffing costs can be calculated based either on existing staff salaries, or the average job market salary for the role you will be hiring for, multiplied for the duration they will be with the project. For example, if you will have a nurse working full-time hours, at £30k per year pre-tax, for the duration of a two-year project, you would cost this staff member at £60k total.

Some members of your team who will not be full-time on the project, usually people like the Chief Investigator, and perhaps your statistician amongst others, should have their salary calculated as an hourly rate. This is usually the amount per hour (GBP) for their salary, multiplied by the number of hours per week (often referred to as %FTE) that they will be working on this specific project, multiplied by the number of weeks for the total duration of the project.

Pricing places can be a little more complex and will require more research. Different facilities, laboratories, and research spaces will charge different rents and fees per project or per financial year, so if they don’t have transparent pricing information available online, you should reach out to them for a quote and to check the likelihood of your project being accepted into the facility (if you have not already got the site in place). There may also be additional fees associated with using a given space, such as a service charge covering janitorial and maintenance costs for the building, insurance fees, and training fees (many facilities will require staff working at that site to undergo site specific training before they can commence their project, including site-specific Health & Safety Training).

Staff and facilities costs are usually the largest chunk of any proposed budget for a research project.

Download this Resource / Contact Us

You can download a copy of this resource here: Funding Proposals & Budgets (PDF)

If you would like to contact us, or if there is a resource you would like to see, reach out to us using this form!