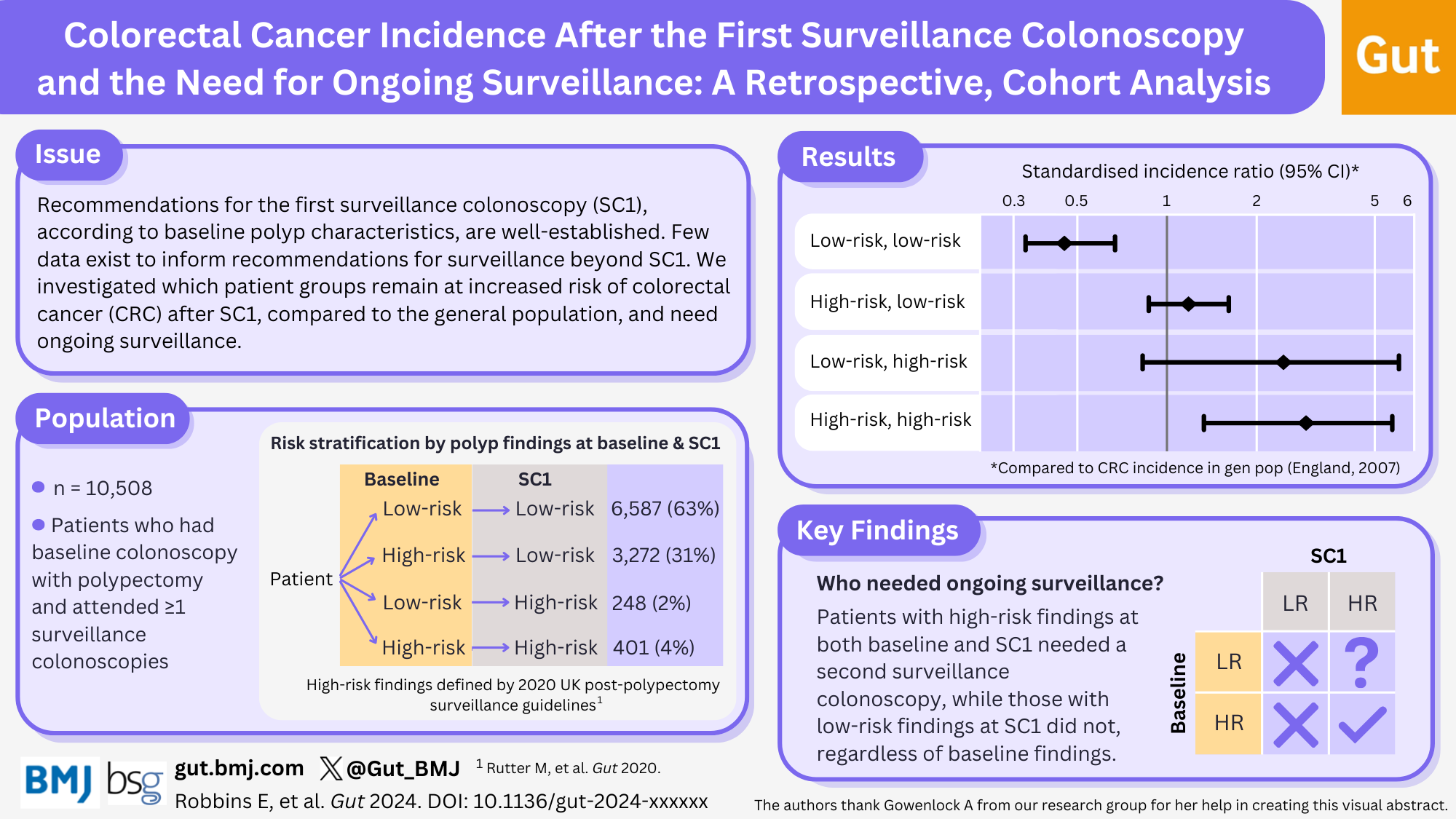

Which patients remain at increased risk of bowel cancer after the first surveillance colonoscopy and need ongoing surveillance?

Our latest paper in Gut BMJ uses data from our All Adenomas study to ask which patients under surveillance for bowel cancer after polyp removal need to continue having surveillance beyond their 1st surveillance colonoscopy.

Bowel polyps and surveillance

Bowel cancer develops from growths called bowel polyps on the inner lining of the bowel. Removing polyps prevents them developing into cancer. Polyps can be removed during colonoscopy, a procedure that uses a flexible tube with a camera at the end to examine the inside of the bowel. However, after polyp removal, some patients are likely to develop further polyps and so remain at increased risk of bowel cancer. These patients are recommended to have one or more check-up colonoscopies to remove any additional polyps or to find bowel cancer at an early stage. This is known as ‘post-polypectomy surveillance’. There is lots of evidence to help identify which patients need a first surveillance colonoscopy (SC1), but there is little evidence to inform recommendations for ongoing surveillance beyond SC1.

Analysis Design

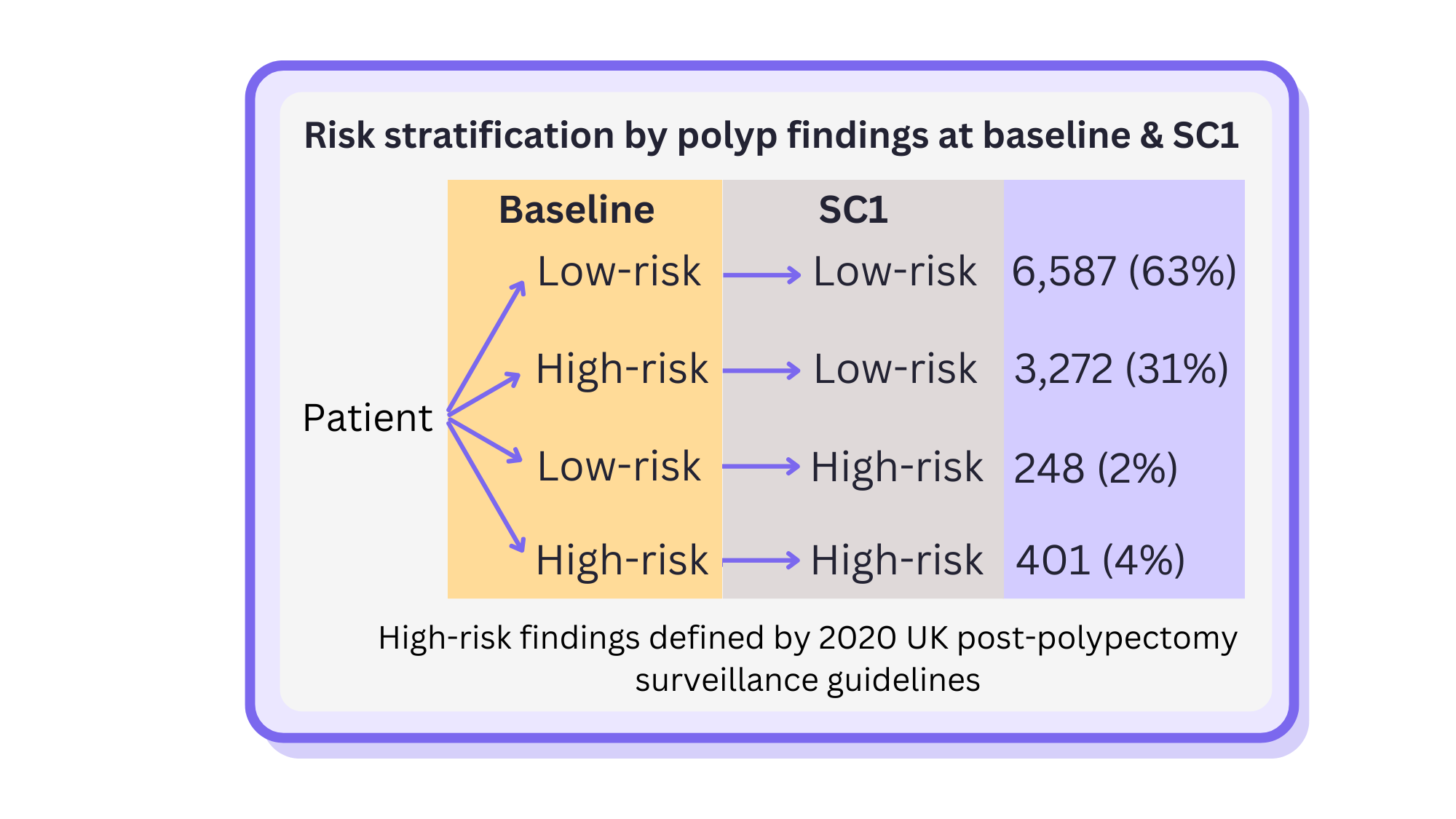

Our new analysis aimed to provide evidence for which patients need ongoing surveillance by identifying those who remain at higher risk of bowel cancer after their SC1, compared with the general population. We included 10,508 patients who had polyps removed at an initial colonoscopy (‘baseline’) and who attended an SC1. We followed them for an average of 8 years after SC1 to determine which patients developed bowel cancer. The patients were split into four groups depending on whether the polyps at their baseline colonoscopy and SC1 were considered low-risk (LR) or high-risk (HR), according to the 2020 UK post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines. The number of new bowel cancer cases in each group was then compared with the number expected in the general population.

What did we find?

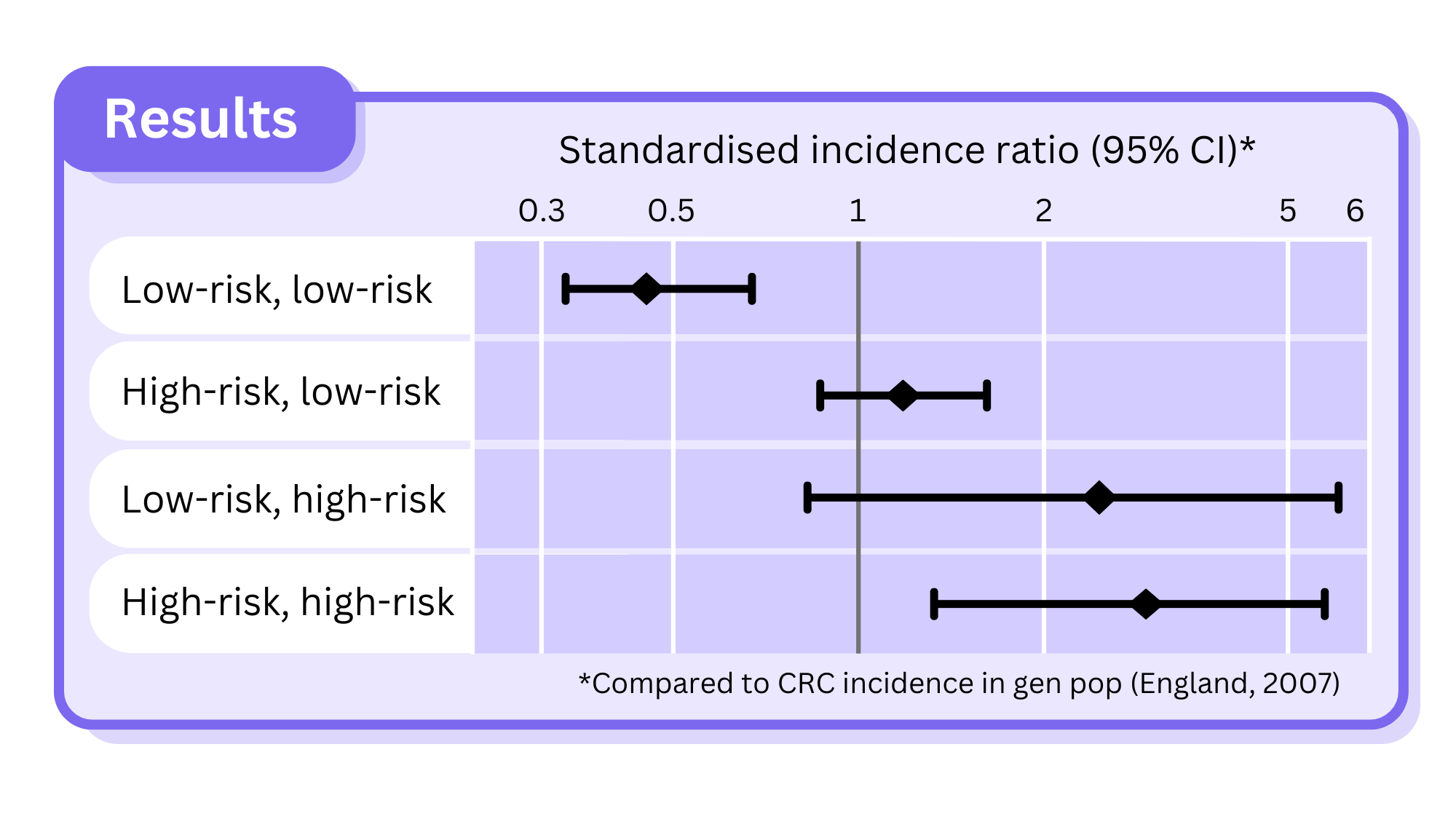

Our results showed that patients with low-risk findings at baseline and SC1 were half as likely to develop bowel cancer, compared to the general population, while those with high-risk findings at both baseline and SC1 were 3 times more likely to develop bowel cancer. The HR-LR group and the LR-HR group had a risk of bowel cancer similar to the general population, although there were few bowel cancer cases in the LR-HR group.

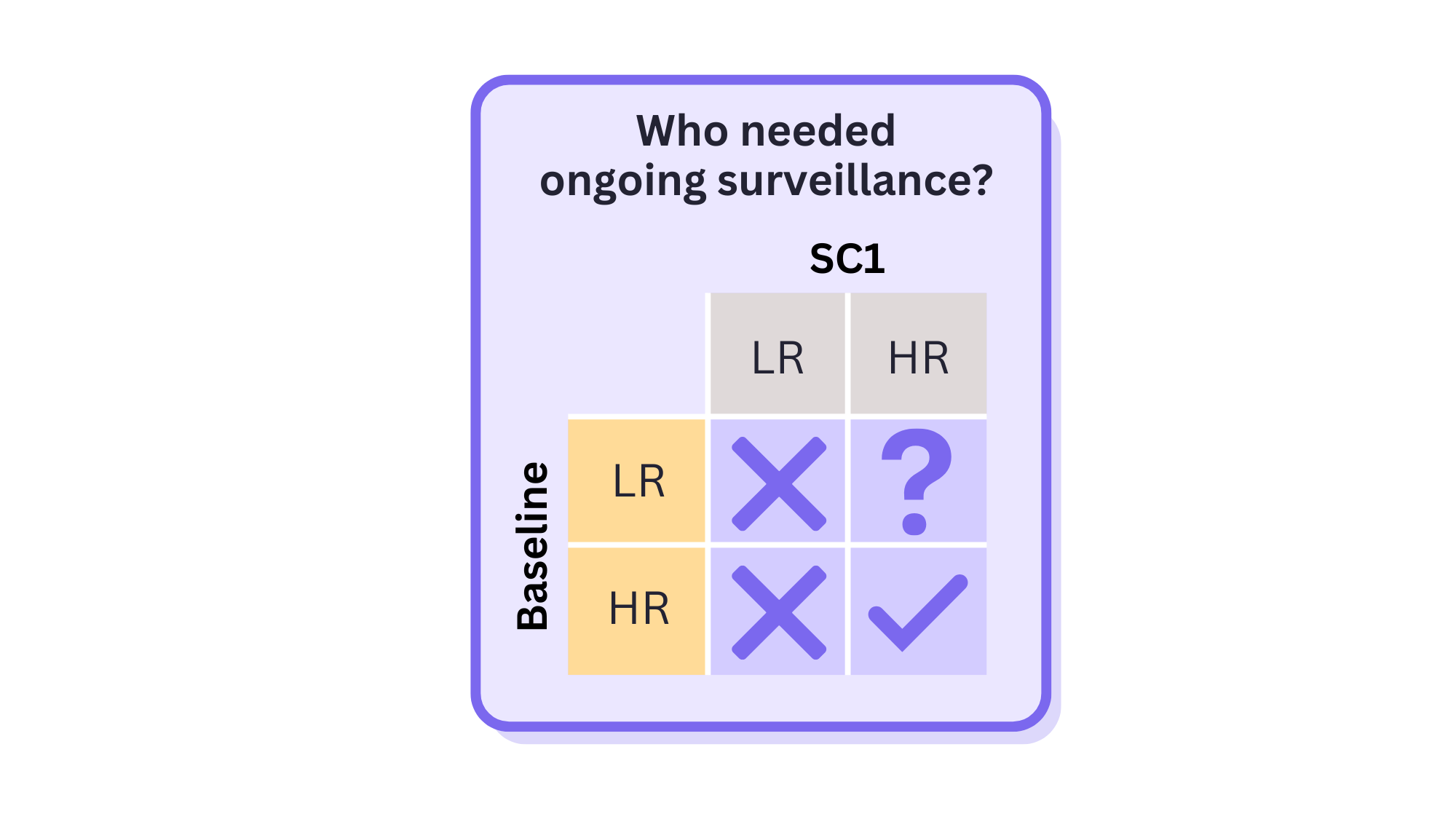

These results suggest that patients with high-risk findings at both baseline and SC1 needed a second surveillance colonoscopy, while those with low-risk findings at SC1 did not, regardless of their baseline findings. We could not draw conclusions for those with low-risk findings at baseline and high-risk findings at SC1 due to the low number of bowel cancer cases.

Why is this important?

While surveillance colonoscopies can help prevent bowel cancer or detect it early, it is important to ensure that they are only offered to those for whom the benefits are likely to be greater than the potential harms (e.g., serious bleeding) from this invasive procedure. We hope that this work will inform future updates of post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines and, in doing so, help to direct surveillance colonoscopies toward those who will most benefit.

This study was conducted by Dr Emma Robbins, Kate Wooldrage and Professor Amanda J Cross of Imperial College London, Dr Matthew Rutter, and Dr Andrew Veitch. This research was funded by the National Institute of Health and Care Research and Cancer Research UK.

Read the paper here: http://gut.bmj.com/cgi/rapidpdf/gutjnl-2024-334242?ijkey=Kw40JGnZcrsDqZ1&keytype=ref