Ancient sediments reveal Antarctica's warmer past

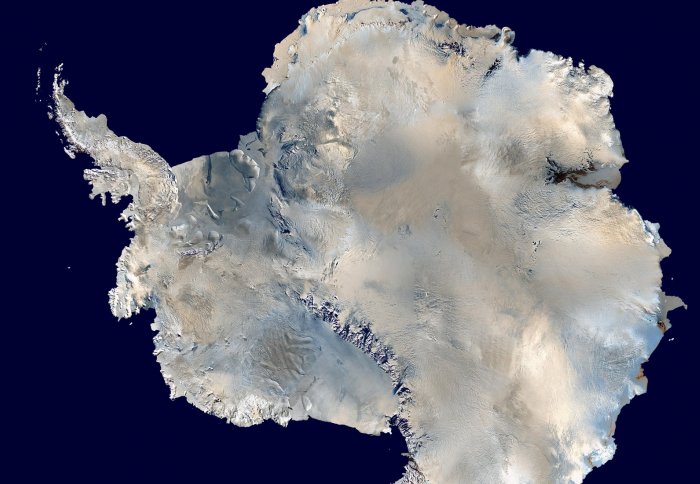

East Antarctica's "stable" ice sheet was vulnerable to past climate warming, a team of Earth scientists from ESE discovered.

Warming temperatures have a profound effect on the Earth’s ice sheets, the huge layers of ice thousands of metres thick that cover Greenland and Antarctica. Over the past twenty years or so, satellites have monitored the changes of these icy landscapes, revealing that ice in Greenland and West Antarctica is melting as a result of warming global temperatures. The melting of ice sheets is important as it contributes to sea level rise, which can have significant impacts on vulnerable coastal states and islands.

So far, however, East Antarctica’s ice sheet, the largest on the planet, has been seemingly stable. One big question Earth scientists have busied themselves with is just how stable this ice sheet is, and whether or not it will be affected by the continuing CO2 emissions and rising temperatures that are projected for the coming century.

To answer such questions, scientists can turn to the past. By looking at rocks or sediments that covered the Earth thousands or millions of years ago, at times when the Earth’s climate was either similar or different to today, they can study how the environment responded to these changing climates.

Between about 5 and 2.5 millions of years ago, during a time we call the Pliocene Epoch, the Earth’s climate was very similar to that which scientists predict for the end of this century. Temperatures were about 3°C warmer than they are today, right in the middle of the range of end-of-century estimates, and CO2 levels were similar to those that are found in the atmosphere at present. By studying ancient sediments from this time, Earth scientists can try to paint a picture of what Antarctica looked like under these conditions, which are similar to those we may be facing in a few decades.

Between about 5 and 2.5 millions of years ago, during a time we call the Pliocene Epoch, the Earth’s climate was very similar to that which scientists predict for the end of this century. Temperatures were about 3°C warmer than they are today, right in the middle of the range of end-of-century estimates, and CO2 levels were similar to those that are found in the atmosphere at present. By studying ancient sediments from this time, Earth scientists can try to paint a picture of what Antarctica looked like under these conditions, which are similar to those we may be facing in a few decades.

Scientists from Imperial College London have done just that. In a paper published last week in the journal Nature Geoscience, Carys Cook, a PhD student at the Imperial College Grantham Institute for Climate Change, Dr Tina van de Flierdt, lecturer in the department of Earth Sciences and Engineering, and their international collaborators were able to uncover some amazing new information about Antarctica’s warmer past.

The team analysed a 75 m thick pile of Pliocene sediment, taken from the seafloor 350 km off the coast of East Antarctica. By looking closely at these sediments, they found that they were made of a repeating sequence of layers containing remnants of tiny algae we call diatoms, and muddy layers with almost no diatoms. The chemistry of the diatom-rich layers revealed that these were formed at times where sea temperatures were higher, with spring and summer temperatures between 2 and 6°C warmer than today.

The authors then looked more closely at where the material in these layers came from. By using very sensitive geochemical fingerprinting tools, they found that the sediment formed during the warmer periods came from a region of Antarctica called the Wilkes Basin, today buried deep under the ice sheet. For material from the Wilkes Basin to have been eroded and transported to the bottom of the sea, this region must have been out in the open. It must have been ice-free.

The authors then looked more closely at where the material in these layers came from. By using very sensitive geochemical fingerprinting tools, they found that the sediment formed during the warmer periods came from a region of Antarctica called the Wilkes Basin, today buried deep under the ice sheet. For material from the Wilkes Basin to have been eroded and transported to the bottom of the sea, this region must have been out in the open. It must have been ice-free.

The authors concluded that during the warmer periods of the Pliocene, part of Antarctica’s giant East ice sheet melted, with the ice retreating up to several hundreds of kilometres inland. The team further suggested that such an amount of melting would have contributed to between 3 and 10 m of sea level rise. They concluded that these regions of the East Antarctica ice sheet were vulnerable to temperatures only a few degrees higher than present.

Back then, with no humans to inhabit the planet, a rise in sea level may not have caused much trouble. Today however, if temperatures continue to rise at the speeds that have characterised the last few decades, such a change could have dire consequences. “If carbon dioxide levels and global temperatures continue to rise, the low-lying regions of the East Antarctic ice sheet may become increasingly vulnerable to large changes, like those that took place during the Pliocene”, says Carys Cook, lead author of the paper.

These results from Antarctica’s past provide important new constraints to help scientists understand the environmental changes we may be facing in the coming decades.

Follow us on Twitter @mle_marion and @imperialrsm for more exciting research and Earth Science news!

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Marion Ferrat

Centre for Environmental Policy