Life's ingredients could have formed near Jupiter

by Gege Li

Researchers have proposed that the building blocks of life may have originated in a turbulent region near Jupiter, not exclusively deep out in space.

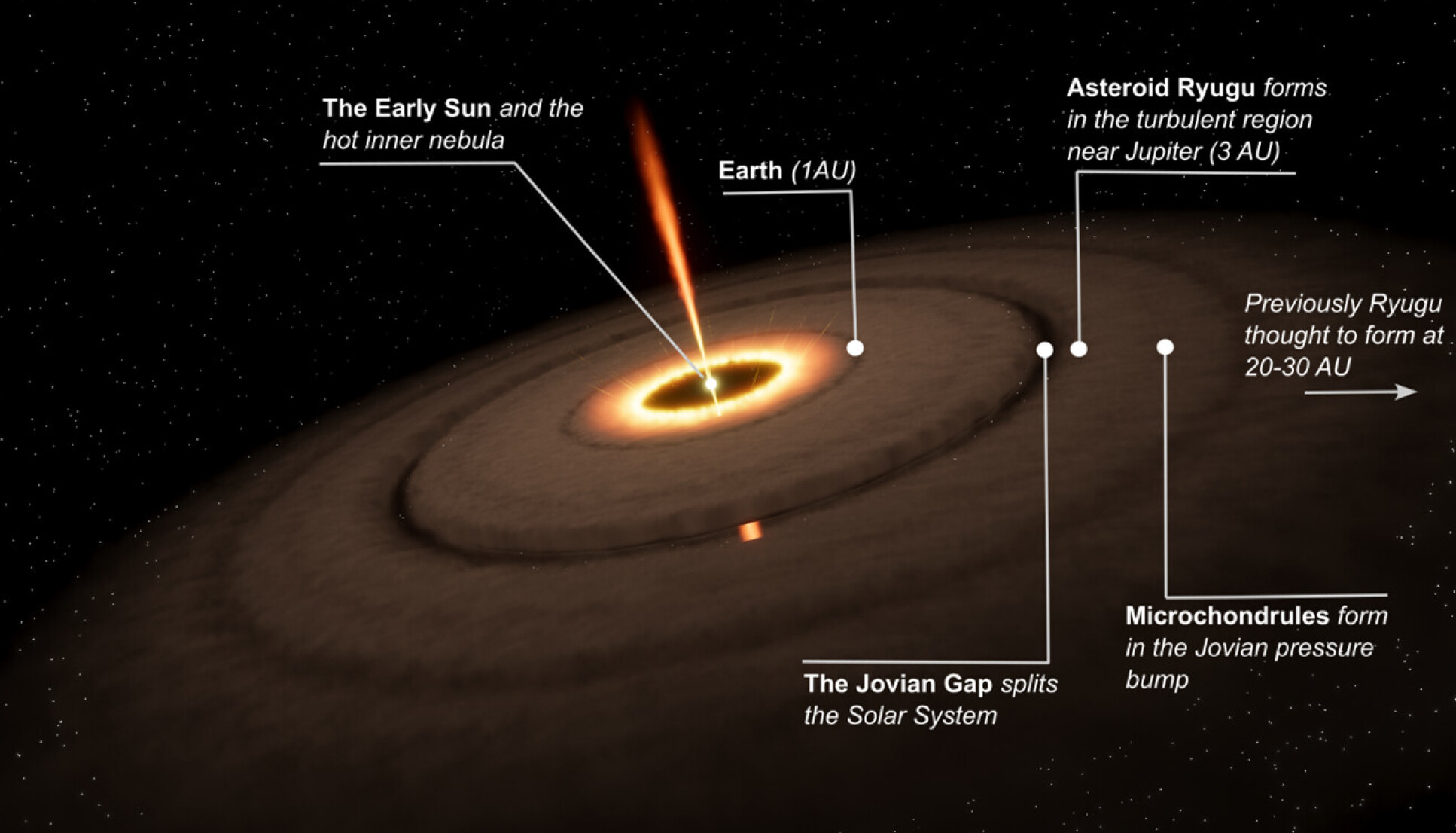

An analysis of samples of the asteroid Ryugu, obtained by the Hayabusa 2 mission, uncovered an abundance of fine particles known as microchondrules, which provide evidence that this asteroid may have formed in a region of the early Solar System just beyond the orbit of Jupiter and not further out in space as previously thought.

Since carbon-rich asteroids like Ryugu likely delivered water and key organic molecules, such as amino acids, that made life possible on Earth, it could be that life’s building blocks came from two distinct locations in space – both its cold distant regions and Jupiter’s turbulent backyard.

"We have now discovered features in the Ryugu asteroid that cast doubt on a distant origin, raising the possibility that Earth’s life-giving materials were also assembled in the wake of giant planets.” Dr Matthew Genge Associate Professor in Earth and Planetary Science, Department of Earth Science and Engineering

“Up until now Ryugu was assumed to have formed at 20-30 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun,” said Dr Matthew Genge, from the Department of Earth Science and Engineering at Imperial College London, who led the study.

“However, we have now discovered features in the asteroid that cast doubt on this distant origin, raising the possibility that Earth’s life-giving materials were also assembled in the wake of giant planets.”

The birth of asteroids

At 4.5 billion years old, Ryugu is an ancient relic from the early Solar System. The Japan Aerospace Agency’s Hayabusa 2 mission, operating from 2018 to 2020, returned just over five grams of the 900-metre-wide asteroid to Earth, revealing that Ryugu contained key components for life, including water, hydroxyl compounds, and the amino acids niacin and uracil.

Ryugu and other asteroids originated within the Solar Nebula, a disk of dust and gas surrounding the young Sun. Over time, temperatures in the Solar Nebula decreased outwards so that water vapour began condensing out as ice, and it was at this location in the early Solar System that Jupiter formed.

This giant planet is so large that it cleared a gap in the nebula and split the Solar System in two – thanks to intense turbulence and force, water-bearing, carbon-rich asteroids are believed to have formed some distance beyond this gap, away from the Sun.

These asteroids are known as primitive objects since they have compositions similar to the Solar System as a whole, with Ryugu being one of the most primitive. It was generally thought that the more primitive an asteroid, the greater the distance from the early Sun it formed. The research team, however, made a surprising discovery in their Ryugu sample.

Turbulent particles

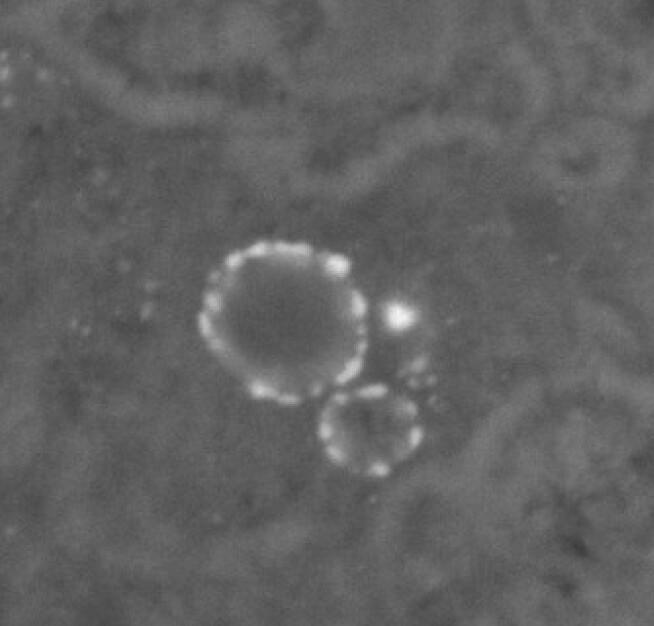

The study, published in Nature Communications, found unexpectedly large numbers of microchondrules within Ryugu – tiny spheres that formed as molten droplets and that wouldn’t be expected to be abundant at large distances from the early Sun.

The microchondrules originally consisted of glass, before being altered by water that formed when ice melted on the asteroid. The team identified the microchondrules due to their sulphide-rims, which could be seen in X-ray CT scans of the one-millimetre-wide sample.

“What was most surprising is there are more microchondrules within Ryugu than in any other known asteroid,” said Dr Genge. “In most other primitive asteroids, microchondrules are accompanied by larger millimetre-sized grains called chondrules, which likewise formed as molten droplets, but we didn’t see that here.”

This abundance of microchondrules and absence of chondrules requires intense turbulence in fast-moving eddies of gas (gas flow) to concentrate the very small particles and remove the large ones.

By that logic, the team reasoned that the required turbulence might have come from just beyond the orbit of Jupiter in the early Solar System, where gas was stirred up in its wake.

Just outside this region was a pressure bump where millimetre-sized grains of asteroid dust were concentrated by gas flow – making this bump an ideal candidate for the team’s theory of a ‘chondrule factory,’ from where microchondrules would have been swept out into the surrounding turbulent region closer to Jupiter, before being concentrated and incorporated into asteroids.

Later, asteroids – from the distant reaches of space and now also Jupiter’s backyard – would migrate closer to the Sun and eventually be well-placed to seed the nascent Earth with the necessary components to kickstart life.

Back in time

There remained one problem: what could explain the highly primitive nature of Ryugu, now that it seems it wasn’t due to large distances?

The answer might lie in the asteroid’s tiny dust grains. Since they are swept along with gas, most small grains escaped heating and so retained their primitive compositions. “It had always been assumed that the most primitive asteroids were fine-grained because they were primitive, but perhaps it is the other way around – they are primitive because they are fine-grained,” suggested Dr Genge.

Ryugu is likely to reveal even more clues about our planet’s formation, as well as Jupiter’s role in distributing asteroids.

“For now, Ryugu has shown us there is more than one way to make these life-seeding asteroids, and, in turn, for the first living things on Earth to appear,” said Dr Genge.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Gege Li

Department of Earth Science & Engineering