One million YouTube hits and rising: Giordano's viral video success

by Jane Horrell

A couple of years ago, in a story we ran on his teaching innovations, Dr Giordano Scarciotti mentioned that he’d like to branch into YouTube...

... fast-forward to this summer and he’s done just that – with spectacular results.

The video that took off tells the story of the inerter — a device invented by Professor Malcolm Smith of Cambridge — and its surprising journey from theoretical control engineering to Formula 1 controversy. The post struck a chord with a huge online audience, crossing half a million views in just three days, and now has well over a million views.

Giordano shares how the video came about, what the experience has meant for him, and why it ties so closely to his professional teaching practice.

A sensational story, and a great storyteller

Authentic enthusiasm on any topic can be highly engaging and empowering people to share their unique stories. Giordano Scarciotti

"The story of this video started with a chance encounter. On a shuttle bus at the IEEE Control and Decision conference last December, I ran into Professor Malcolm Smith who was my PhD external examiner.

Professor Smith is renowned in the control community as the inventor of the inerter, a device whose story has long fascinated me. His work fundamentally showed that the classic force-current analogy taught for decades was incomplete, a fact that always stuck with me.

The inerter has also a dramatic backstory, playing a central role in the 2007 Formula 1 “spygate” scandal. It’s a perfect example of a deep theoretical concept from control engineering having a massive, real-world impact. I’ve used this story for years to open my control systems lectures, including the one I gave for my lectureship application here at Imperial!

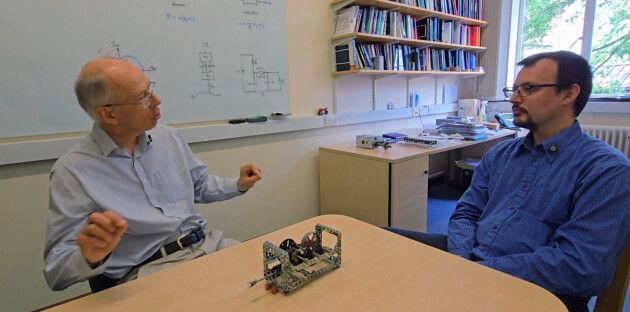

On the bus, I mentioned to Professor Smith that I had recently started a YouTube channel and would love to interview him about the inerter. He was enthusiastic, and six months later, I was in Cambridge filming with him.

On the bus, I mentioned to Professor Smith that I had recently started a YouTube channel and would love to interview him about the inerter. He was enthusiastic, and six months later, I was in Cambridge filming with him.

The editing process was intense. From over an hour and a half of footage, I tried to squeeze all the content within a 50-minute video, often working late into the night during a family holiday – it's a passion project, and you truly have to enjoy the process.

The video’s success, apart for the obvious luck, was a combination of passion, strategy, and timing. Professor Smith was a fantastic storyteller, and I poured a lot of effort into making the narrative compelling and digestible to a non-specialist public.

After publishing, a carefully worded social media post was picked up by the moderators of a major Formula 1 online forum and pinned, which provided the initial explosion of interest. This, combined with a Grand Prix-free weekend and heightened F1 interest in the US, created the perfect conditions for this story. Still, my optimistic goal was 10000 views. To see it cross half a million in 3 days was a shock for both of us."

How does this connect with your approach to teaching and public engagement?

For me it is not easy to create a compelling stand for the Great Exhibition Road Festival as my work is deeply mathematical. However, with a well-crafted video I can make these abstract concepts accessible and exciting.

"This project connects directly with several of my professional goals. First, as a community, we in control engineering have long discussed the challenge of outreach. The field is ubiquitous but poorly understood by the public. My channel is my small attempt to bridge that gap. I’m particularly proud that over a million people have now at least heard the term "multivariable robust control", which we explain right at the beginning of the video.

Second, YouTube has provided an avenue for public engagement that suits my theoretical research. For me it is not easy to create a compelling stand for the Great Exhibition Road Festival as my work is deeply mathematical. However, with a well-crafted video I can make these abstract concepts accessible and exciting.

Finally, it’s a powerful tool for motivating my students. I have used my videos to supplement my courses on Blackboard, to provide motivation to study control engineering and optimisation. Last year, I did so with 100 subscribers, just 3 weeks after starting my channel. I look forward to seeing the reaction from this year’s cohort when they see that now the channel has over 11,000."

What do you see as the strengths and limitations of YouTube as a medium for technical content?

"It’s a common misconception that YouTube is only for popular science. There are highly technical channels with huge followings, featuring full-length lecture series. The platform can certainly support deep, complex content – if you know how to find this within the virtually infinite library.

The main limitation, of course, is the lack of direct interaction: the inability to conduct live experiments or have student-to-student discussion. However, this also serves as a critical mirror for our own teaching. If a lecture consists solely of a two-hour monologue, it faces very strong competition from expertly produced online content. This reality encourages us to focus on what makes in-person teaching irreplaceable: interactivity and hands-on learning. As you know, I have always been a strong proponent of flipped classroom and team-based learning to maximise the interaction time with students.

Authentic enthusiasm on any topic can be highly engaging and empowering people to share their unique stories, and expertise may be the most impactful way forward. On this note, if anyone reading this wants to suggest an interesting story or technology, maybe from an EEE lab, let me know!"

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Jane Horrell

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering