Health

by Gege Li

A substantial ‘transition energy’ is required to phase out fossil fuels in the European Union, a study by Imperial College London has found, revealing that faster transitions demand significantly larger, and potentially disruptive, reallocations of energy resources within society.

By developing a model that calculates the electricity needed to replace fossil fuels in each major economic sector, from transport to heating, plus the required energy to build the infrastructure that make this switch possible, the research highlights that our path to net-zero needs a rethink – requiring coordination across industries and temporary cuts to our non-essential energy use, such as flying, driving, or manufacturing non-essential goods.

In accounting for all types of infrastructure and their energy requirements, our work has quantified this massive, understudied effort [to phase out fossil fuels], which must be planned for and inevitably involves a trade-off with the energy we currently use in our daily lives. Ugo Legendre PhD researcher, Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial

“A viable plan for the energy transition will come with a substantial energy bill, which is rooted in the energy required to build the very tools that will give us renewable energy, such as power plants and electric grid extensions,” said lead author Ugo Legendre, a PhD researcher in the Department of Earth Science and Engineering at Imperial.

“However, these energy requirements are typically absent in mainstream discussions about the energy transition that concern the public, politics and even the economy, despite costs increasing as we look to faster transition scenarios, such as by 2050.

“In accounting for all types of infrastructure and their energy requirements, our work has quantified this massive, understudied effort, which must be planned for and inevitably involves a trade-off with the energy we currently use in our daily lives.”

The global shift away from fossil fuels relies on building new energy systems from the ground up. To achieve this, society must spend a huge amount of energy today to manufacture the likes of wind turbines and solar panels. This ‘transition energy’ is a crucial upfront cost, but what will it take?

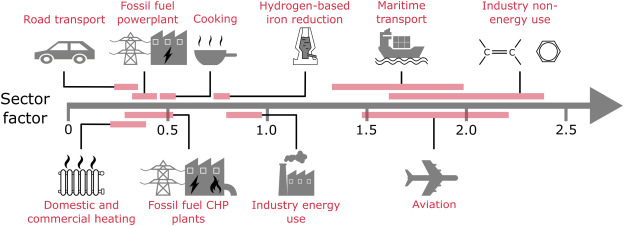

To investigate the requirements of and barriers to fast energy transition scenarios, the team’s model firstly estimates how efficiently electricity can substitute fossil fuels in major economic sectors. Based on how fast we aim to phase out fossil fuels, it calculates the additional amount of electricity we need to generate each year. It then goes on to estimate how much infrastructure (and the associated amount of material) is necessary to produce, transport and use the electricity, and finally the amount of energy required to extract, transform and transport these materials.

Applying the model to four EU phase-out scenarios (by 2035, 2050, 2075 and 2100), the study, published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, found that the energy required to build a new low-carbon system increases with the speed of the transition.

In the most ambitious scenario – phasing out all fossil fuels by 2035 – the annual energy requirements for the transition would peak at an amount equivalent to 39% of the EU’s current total energy supply. Even when averaged more evenly over time, this figure remains at a substantial 25%. Meanwhile, for a 2050 phase-out, the figures are 24% and 19%, respectively.

A large, comprehensive infrastructure rollout requires an equally broad and hefty upfront energy investment, and this could temporarily tighten the net energy available for other services. Dr Pablo Brito Parada Associate Professor, Department of Earth Science and Engineering

“What is critical is that in the faster scenarios, this transition energy exceeds the energy we currently spend on simply extracting and refining fossil fuels – requiring us to divert significant amounts of energy from transport, manufacturing or heating homes and offices, for example,” said co-author Dr Pablo Brito Parada, Associate Professor in Sustainable Minerals Processing in the Department of Earth Science and Engineering.

“A large, comprehensive infrastructure rollout requires an equally broad and hefty upfront energy investment, and this could temporarily tighten the net energy available for other services. In addition to this, we will need to continue spending some energy obtaining fossil fuels for the duration of the transition, and as we reach a higher share of intermittent renewable electricity in our electric system, curtailment and electricity storage inefficiencies will also eat into our available energy supply.”

The model’s sector-by-sector analysis identifies where the biggest energy investments are needed. Electrifying road transport accounts for the largest share (29%) of total transition energy requirements, followed by industrial non-energy uses (21%), such as producing chemical feedstocks for plastics, fertilisers or lubricants.

What’s more, the study reveals that for road transport, over 70% of its energy requirement is tied to manufacturing end-use devices (primarily electric vehicle batteries and charging points) rather than the power plants themselves. This highlights a unique pressure point and suggests strategies like reducing vehicle size or increased sharing could significantly lower the sector’s burden.

“All these types of infrastructure must be developed in a coordinated way, which adds to the difficulty,” said Legendre. “Otherwise, some of the infrastructure produced will be temporarily obsolete. For example, every electric car we build requires a proportional number of solar panels and grid extensions to come online at the same time.

“A sound transition plan must be drawn with all industries and companies involved on board – from wind turbines to electric grid management to car manufacturers and steel makers.”

The real challenge in getting the fossil fuel phase-out over the line is a strategic one. While a rapid transition is clearly demanding, delaying it poses a severe energy security threat for import-dependent regions like the EU and UK.

“Although it is tempting to settle for the slower transition and accept higher greenhouse gas emissions, there is an additional danger since on average, the combined regions import more than 90% of their oil and 80% of their gas,” said Legendre.

Many oil-exporting countries may be unable to keep increasing their production while their domestic consumption rises, resulting in less oil available to export. Consequently, regardless of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, deploying non-fossil energy sources too slowly risks a future energy crisis. A similar situation is likely to evolve for gas supplies, albeit with approximately a decade of delay.

Many oil-exporting countries may be unable to keep increasing their production while their domestic consumption rises, resulting in less oil available to export. Consequently, regardless of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, deploying non-fossil energy sources too slowly risks a future energy crisis. A similar situation is likely to evolve for gas supplies, albeit with approximately a decade of delay.

Legendre added: “It is a ‘catch-22’ situation. Waiting with the transition is not an option, but doing it fast has its own challenges. We have difficult decisions which must be taken sooner rather than later, as delaying these only makes things worse on both the energy security and the climate change aspects.”

While not impossible, the study underscores that fast transitions will require an unprecedented level of planning and prioritisation that isn’t yet happening today.

The team is calling for future research and policy planning to adopt greater awareness of physical constraints, clearer system boundaries and to consider compromise options such as targeted sufficiency.

The path forward must be built with the urgency of climate change, the physical realities of the energy system, and the inevitability of fossil fuel depletion in mind. Ugo Legendre PhD researcher, Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial

One key strategy to ease the transition is in maintaining or expanding existing low-carbon energy sources which can modulate their electricity production like some nuclear power plants and hydropower, reducing overall system energy requirements and storage needs.

“Ultimately, there is no way forward without compromise,” said Legendre. “The necessary reallocation of energy could lead to societal disruptions if not managed carefully, with impacts likely felt unevenly across different populations.

“The path forward must be built with the urgency of climate change, the physical realities of the energy system, and the inevitability of fossil fuel depletion in mind.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Faculty of Engineering

Health

Health

Cross-faculty

Engineering

Health

Health

Health

Discover more Imperial News

Search all articlesDiscover more Imperial News

Search all articles