Health

by Eliza Kania

Two clinical trials have recently delivered contrasting results on GLP-1 drugs for Alzheimer's disease. The medications, originally developed to mimic the hormone controlling hunger and blood sugar, showed strikingly different outcomes.

Professor Paul Edison, Professor of Neuroscience at Imperial College London, was leading one of the studies and was heavily involved in the other one. Despite these contrasting results, he believes these trials offer valuable insights that “give some hope for the future” in developing novel treatment approaches.

In late November 2025, media headlines reported the pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk’s failure in a major Alzheimer’s study. The EVOKE and EVOKE+ research programmes tested an oral version of semaglutide – the same substance used in the popular Ozempic/Wegovy injections– but found it failed to slow disease progression in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease.”i

On December 1, 2025, Imperial led a trial using liraglutide – a drug from the same GLP-1 class – produced surprisingly promising results: nearly 50% less brain volume loss and an 18% slower decline in cognitive function.ii These promising results were published in Nature.iii

So, what can we learn from these contrasting findings?

In search of a universal drug

Alzheimer’s disease is the outcome of multiple simultaneous processes: accumulation of toxic proteins (amyloid and tau), chronic inflammation, damage to connections between neurons, and the brain’s loss of insulin sensitivity. Given this complexity, effective treatment requires either multi-drug therapy targeting each of these mechanisms separately or finding a universal drug.

Such drugs may include those from the GLP-1 class. Originally, semaglutide or liraglutide were used to treat diabetes and obesity (their injectable versions are known as, respectively, Ozempic and Saxenda). They are now raising hopes in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, as they simultaneously affect several factors causing Alzheimer’s.

Professor Edison first proposed the hypothesis about the potential use of GLP-1 in Alzheimer’s in 2010 and secured funding from three organisations: the Alzheimer’s Society in the United Kingdom, the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation in the USA, and the pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk.

He was involved in both trials: the smaller one, conducted at Imperial College London, of which he was Chief Investigator, and the larger, industry-sponsored trial for Novo Nordisk.

Same class of drugs, different outcomes

The Imperial College ELAD study was a small-scale academic trial (phase 2b), involving 204 non-diabetic patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. This was an exploratory study – the aim was not to immediately prove the drug’s efficacy, but to understand how injectable liraglutide works in the brain.

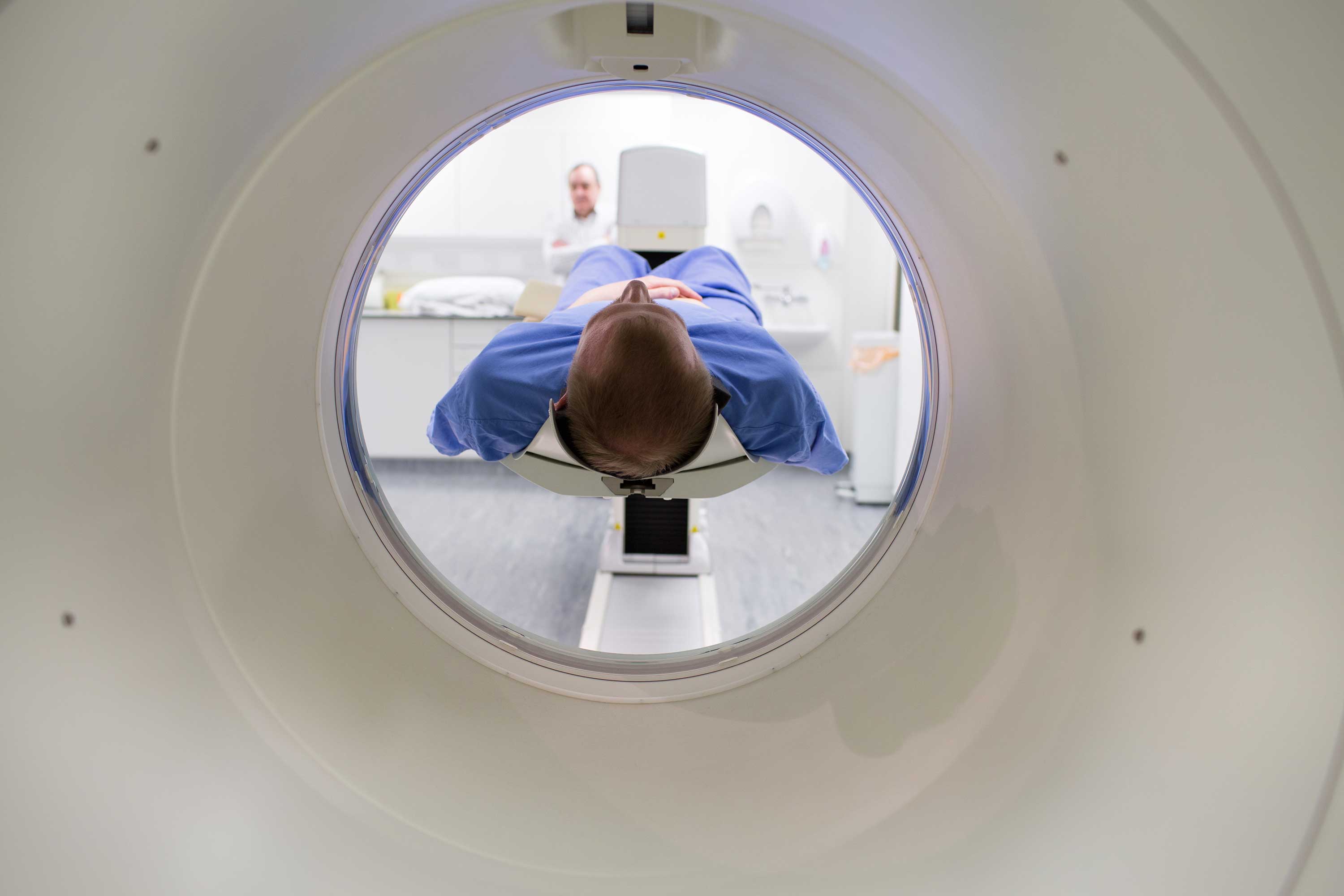

The researchers focused on three aspects: how the brain utilises glucose (using PET scans), how cognitive functions change (memory and thinking tests), and how brain volume changes (MRI). While the primary outcome measure (glucose metabolism) showed no difference, other predefined secondary outcomes were promising – slowed brain atrophy and improved memory.

Meanwhile, the Novo Nordisk programme comprised two large-scale clinical trials (EVOKE and EVOKE+) with over 3,800 participants with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. The programme tested a tablet – oral semaglutide – in a large-scale trial, trying to answer the question of whether it would slow memory loss.

In this case, Professor Edison was the Principal Investigator at Imperial/Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and a member of their scientific advisory board, contributing to scientific discussions around mechanism, challenges with the oral compound, and what the results mean for the broader GLP-1 field in neurodegeneration.

One of the key challenges for both studies was whether the drugs reach the brain. Injectable liraglutide can enter the brain, though only in small amounts (Imperial study). Oral semaglutide (Novo Norilsk), on the other hand, was designed to survive the digestive system. As Professor Edison emphasised, this drug “is chemically optimised for stability and absorption in the gut and for prolonged systemic exposure. Those same properties appear to reduce its ability to enter the brain (at least retrospectively looking at it)”.

This may explain why the two trials produced different results, even though both drugs belong to the same family.

Promising direction

The Novo Nordisk trial’s negative result proved paradoxically valuable. As Professor Edison noted, this means “a negative trial result may indicate lack of drug access to the brain, rather than failure of the concept itself.”

Dr Ivan Koychev, Clinical Associate Professor in Neuropsychiatry at Imperial, pointed out potential future developments: “This is a recurring theme in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. When pathology is advanced, preventing further biochemical decline is not necessarily enough to restore complex neural networks that have already deteriorated.

A negative trial result may indicate lack of drug access to the brain, rather than failure of the concept itself. Professor Paul Edison Professor of Neuroscience

The EVOKE results reinforce the need to test these agents much earlier, ideally years before symptoms emerge, when neuronal systems are more intact, and the potential for clinical benefit is greater”, Dr Koychev explained.

“So, while semaglutide did not slow progression in established symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease, these findings do not diminish the preventive epidemiological signal. Instead, they point us toward the next logical steps: targeting preclinical stages, leveraging biomarkers to identify those at highest risk, and understanding how metabolic interventions can reshape the trajectory of neurodegeneration before symptoms appear”.

Broader evidence supports this preventive approach. In his plenary lecture at the American Academy of Neurology meeting in April 2025, Professor Edison highlighted that observational studies consistently show GLP-1 drugs reducing the risk of cognitive decline. The drugs target several disease mechanisms simultaneously, which may make them effective when used early, much like statins prevent heart disease rather than treating it once it's advanced. He also highlighted the potential challenges with these drugs due to relatively low levels of the drugs getting into the brain.

Professor Edison also indicated that the EVOKE trials have a particular societal impact, as they help “reset expectations” and guide future investment in Alzheimer’s research. “There has been enormous public enthusiasm around GLP-1 drugs, and some hope that their success in diabetes and obesity might translate rapidly into benefits for dementia. These studies show that translation is not automatic and that careful attention to mechanism matters,” the scientist explained.

In the long term, an oral compound which could influence neurodegenerative processes could have a significant impact. For patients and families, whilst they may be disappointed by these findings, as Professor Edison emphasises, a completely novel mechanism of treatment offers some hope for the future.

Learn more

Broader media coverage

***

[i] Obesity jab drug fails to slow Alzheimer's, “BBC”; Novo Nordisk's Ozempic Pill Fails in Long-Shot Alzheimer's Effort, “Bloomberg”; Novo Nordisk shares slump after drug failure in Alzheimer’s trial, “Financial Times”; Undeterred by Novo Nordisk failure, scientists consider GLP-1s as Alzheimer’s prevention, “Reuters”, Novo Nordisk shares slide after Ozempic pill fails in Alzheimer’s trial, “The Guardian”.

[ii] Weight-loss drug liraglutide slowed Alzheimer’s decline, “Imperial College London”.

[iii] Liraglutide in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a phase 2b clinical trial, „Nature”.

[iv]Explaining the amyloid research study controversy, “Alzheimer’s Society”;

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Faculty of Medicine

Health

Health

Cross-faculty

Engineering

Health

Health

Health

Discover more Imperial News

Search all articlesDiscover more Imperial News

Search all articles