Health

by Meesha Patel

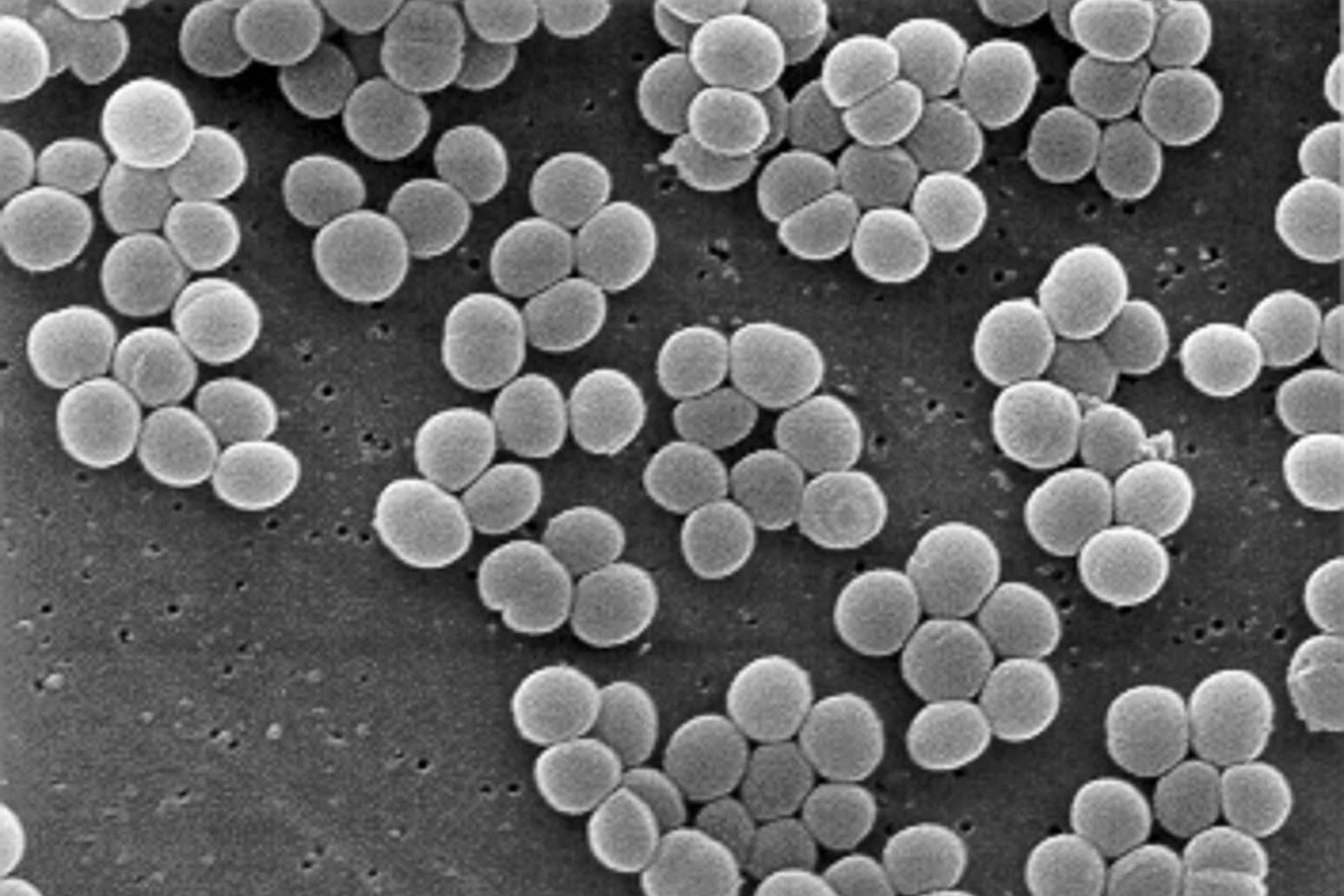

A study of the human nasal microbiome has allowed scientists to rethink how bacterial communities interact in the nose.

People who persistently carry Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) in their nose have fewer species of other bacteria, while certain bacteria may help to prevent S. aureus colonisation.

Persistent Staphylococcus aureus carriage is a well-recognised risk factor for infection, particularly in hospital settings. By identifying the bacterial profiles that protect against S. aureus colonisation, our findings could inform new, microbiome-based strategies to reduce infection risk without relying on antibiotics. Dr Dinesh Aggarwal Department of Infectious Disease

These findings are from the largest-ever study of the nasal microbiome, published in Nature Communications.

In the study, researchers from Imperial College London, the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Cambridge, and the University of Birmingham analysed nasal swabs from over 1,000 healthy blood donors to explore the bacterial communities living in the human nose.

The research sheds new light on how interactions between different bacterial species are key to understanding why some people are persistently colonised by S. aureus and provides insight into who may be most at risk of S. aureus infection.

Dr Dinesh Aggarwal, first author and Clinical Lecturer in the Department of Infectious Disease, said, “Persistent Staphylococcus aureus carriage is a well-recognised risk factor for infection, particularly in hospital settings. By identifying the bacterial profiles that protect against S. aureus colonisation, our findings could inform new, microbiome-based strategies to reduce infection risk without relying on antibiotics.”

S. aureus is a common bacterium that lives without symptoms in the nose of about 30% of people. Normally, it does not cause harm, but if it enters the body through wounds, cuts, or surgical incisions it can cause serious infections. Infections from S. aureus are the second most common cause of mortality related to bacterial infections, after tuberculosis, causing roughly one million deaths per year. Some strains, such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), are resistant to common antibiotics, making infections harder to treat.

People who carry S. aureus have been classified into three groups: persistent carriers, intermittent carriers, and non-carriers. Persistent carriers always test positive for carrying S. aureus. An intermittent carrier sometimes tests positive, and non-carriers never show positive.

Because S. aureus carriage increases the risk of post-operative infections, hospitals often screen patients before procedures, such as joint replacements, and may provide nasal treatments to reduce the bacterium in the nose. However, the nasal microbiome, unlike the gut microbiome, has not been studied in large populations, leaving much unknown about how S. aureus interacts with other nasal bacteria.

In this new study, researchers sought to analyse a much larger group of people than in previous studies to thoroughly understand how different bacteria can influence S. aureus colonisation.

The study recruited volunteers from across England who had previously taken part in trials of blood donation led by the University of Cambridge. The team collected three weekly nasal swabs from 1,100 healthy adults, and each sample was tested for S. aureus. Researchers then used advanced statistical methods to uncover patterns in the nasal microbiome and determine whether carrying S. aureus could be predicted by the bacterial community present.

They found two main patterns in the microbiome. Firstly, the team found that persistent carriers have a distinct microbiome with an abundance of S. aureus and a lack of other species in the nasal samples.

Secondly, certain bacteria such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Dolosigranulum pigrum, and Moraxella catarrhalis were found to be less common in persistent carriers. The researchers suggest that these other species might help block S. aureus colonisation in non-carriers.

Using machine learning, the researchers were also able to predict who is persistently colonised with S. aureus particularly well, offering a possible method to predict risk of infection.

Interestingly, the researchers also propose that intermittent carriers are just misclassified persistent carriers or non-carriers — the notion of intermittent carriage does not represent a true biological state. They are likely to be non-carriers who have been exposed to and picked up S. aureus for a short period of time.

“This is the largest study to date of the bacteria that live in our noses, and it shows that Staphylococcus aureus doesn’t act alone — it’s part of a whole community. We found that some bacterial neighbours can help keep Staph out, offering exciting new directions for preventing infections using new methods,” comments Katie Bellis, co-author and Staff Scientist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

This study highlights that interactions between different bacterial species are key to understanding why some people are persistently colonised by S. aureus, placing them at greater risk of infection. The findings have important clinical implications. Identifying carriers of S. aureus could help predict infection risk and enable healthcare professionals to better target those who may benefit from preventive decolonisation treatments.

The researchers now want to build on this piece of the puzzle by looking into whether certain risk factors, such as medical conditions, sex, human genetics or other environmental exposures influence S. aureus carriage.

Dr Ewan Harrison, Senior author and Group Leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and University of Cambridge said, “Everyone’s nose microbiome is unique, and this study shows that the bacteria living there can have a big impact on our health. By studying thousands of samples, we can finally see the bigger picture of how our natural bacteria either help or hinder infection.”

Adapted from a news story on the Wellcome Sanger Institute website

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Faculty of Medicine

Health

Health

Cross-faculty

Engineering

Health

Health

Health

Discover more Imperial News

Search all articlesDiscover more Imperial News

Search all articles