New research identifies a mechanism of action for the GLP-1 receptor, the target of GLP-1 diabetes drugs

Research led by Imperial has uncovered a hidden cellular mechanism that explains how widely used type 2 diabetes drugs signal to protect the pancreas, opening up new possibilities for improving future diabetes therapies.

We believe that the receptor uses the ER as a bridge to access other cellular organelles, opening exciting possibilities to find new ways to improve diabetes therapies." Professor Alejandra Tomas Catala Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction

The paper, published in Nature Communications, uncovers how the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) forms a specialised signalling hub inside pancreatic β-cells that supports healthy mitochondria and boosts insulin secretion.

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are well-established treatments for type 2 diabetes and obesity. They help lower blood sugar by stimulating insulin release, but until now it has remained unclear how they also strengthen the mitochondria, the tiny energy-producing structures that keep β-cells functioning and resilient.

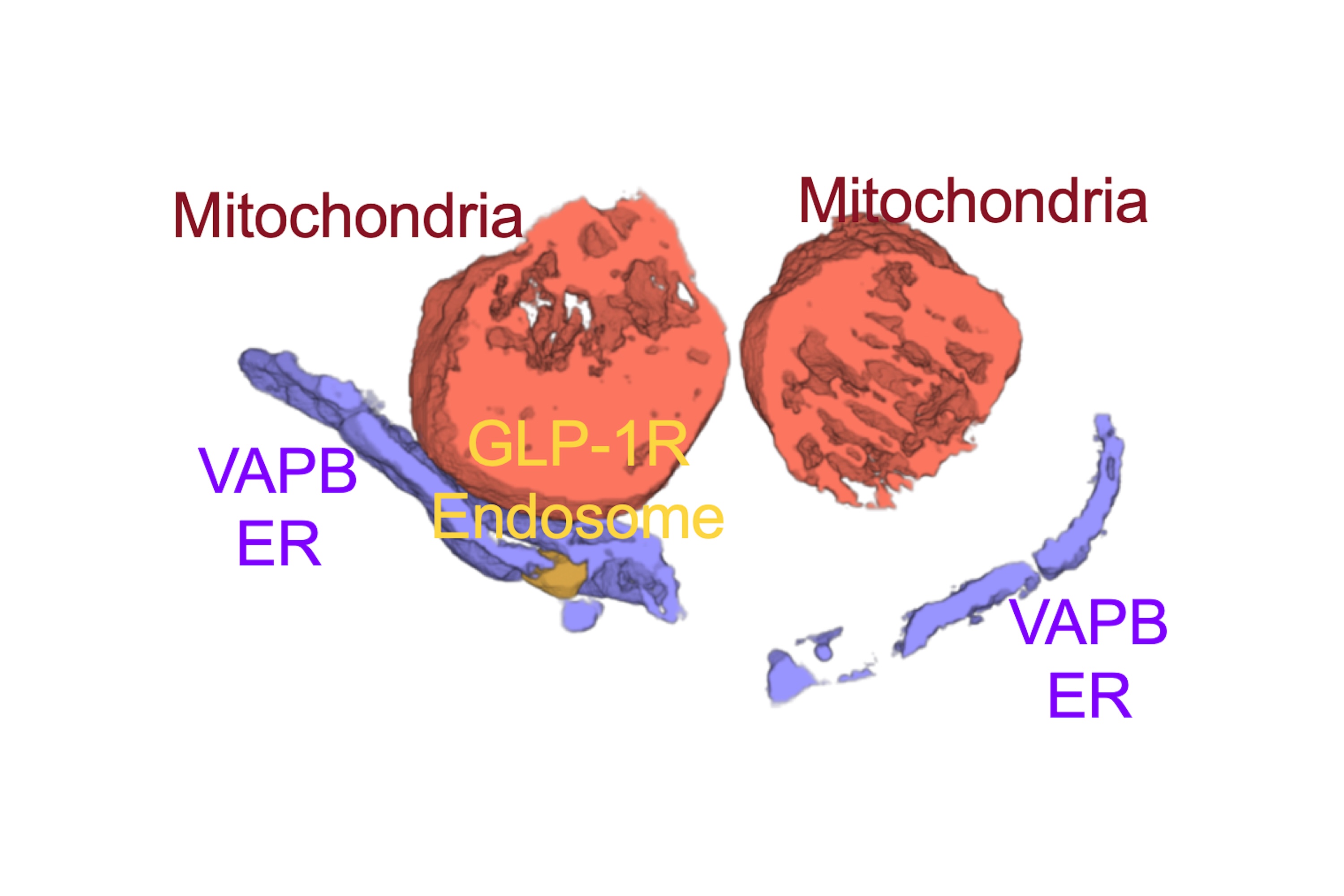

Once activated by GLP-1RAs, the GLP-1 receptor is known to move inside the cell via transport vesicles called "endosomes". The researchers found that those endosomes then hook at special locations of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) called "membrane contact sites". These locations are important hubs where signals are exchanged, allowing the GLP-1R to send signals into mitochondria to boost their regeneration in partnership with the proteins VAPB and SPHKAP, helping β-cells survive cellular stress and continue to produce insulin effectively.

The work also suggests that the GLP-1R uses the ER as a platform to reach and signal into many different cellular organelles, not just mitochondria. The team is now mapping these signals to understand the full extent of this communication network. They are also exploring whether related receptors, such as GIPR and GCGR, behave in a similar way in tissues like the liver and fat.

Next, the researchers will test the importance of this mechanism in living organisms. They are generating mice in which the protein SPHKAP can be specifically deleted from β-cells, allowing them to examine how disrupting this signalling hub affects pancreatic function and GLP-1R signalling. Another key question is whether the pathway is impaired in type 2 diabetes, and whether it can be restored with specific treatments.

Professor Alejandra Tomas Catala, lead author and Head of Section of Cell Biology and Functional Genomics in the Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, said: “Our study reveals an entirely new way in which GLP-1 receptor agonists protect pancreatic β-cells. We found that the receptor doesn’t just signal at the cell surface, it moves inside the cell to form a specialised hub at ER contact sites. This hub reorganizes mitochondria, making them stronger and more efficient, which is crucial for insulin secretion and β-cell survival. Beyond this effect, we believe that the receptor uses the ER as a bridge to access other cellular organelles, opening exciting possibilities to find new ways to improve diabetes therapies. Finally, this is likely to be a mechanism used by many other receptors in other tissues, so that the implication of understanding how these signalling hubs work is far reaching for many human disorders beyond diabetes.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Article people, mentions and related links

Benjie Coleman

Faculty of Medicine