Imperial researchers help reveal new way to track crucial cell surface messengers

New chemical toolkit lets researchers track and redesign proteoglycans, opening fresh insights into development and cancer signalling.

New chemical toolkit lets researchers track and redesign proteoglycans, opening fresh insights into development and cancer signalling.

The study, funded by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), was led by Dr Ben Schumann, formerly a group leader at the Francis Crick Institute and lecturer in the Department of Chemistry at Imperial, and has unveiled a powerful method to track and study proteoglycans - complex sugar‑coated molecules that help cells sense and respond to their environment.

Published this week in Nature Chemical Biology, the research introduces an innovative chemical biology toolkit that allows scientists to label and follow these molecules in living cells for the first time.

Understanding the cell’s conversation layer

Many of a cell’s most important decisions begin at its surface. Here, large sugar‑protein structures known as proteoglycans act as sensitive receivers detecting growth cues, guiding tissue development, and modulating responses to infection or injury.

But despite their central role, proteoglycans have been notoriously difficult to study. Their unique combination of long, complex sugar chains and core proteins makes them resistant to standard analytical tools such as mass spectrometry.

“Proteoglycans are vital for the growth of most of our organs - alterations in these molecules are lethal in developing embryos," explains Dr Schumann. “Although studies have identified just about a hundred in human cells, there are likely many more. At the moment, it’s a clunky process to identify just one proteoglycan at a time, work out its structure and what it’s doing. I wanted to try and streamline this.”

Click chemistry meets bump‑and‑hole engineering

To overcome this challenge, the team, led by researchers Zhen Li and Himanshi Chawla, adapted a Nobel Prize‑winning chemistry technique known as click chemistry, which allows molecules to be “clicked” together with high precision.

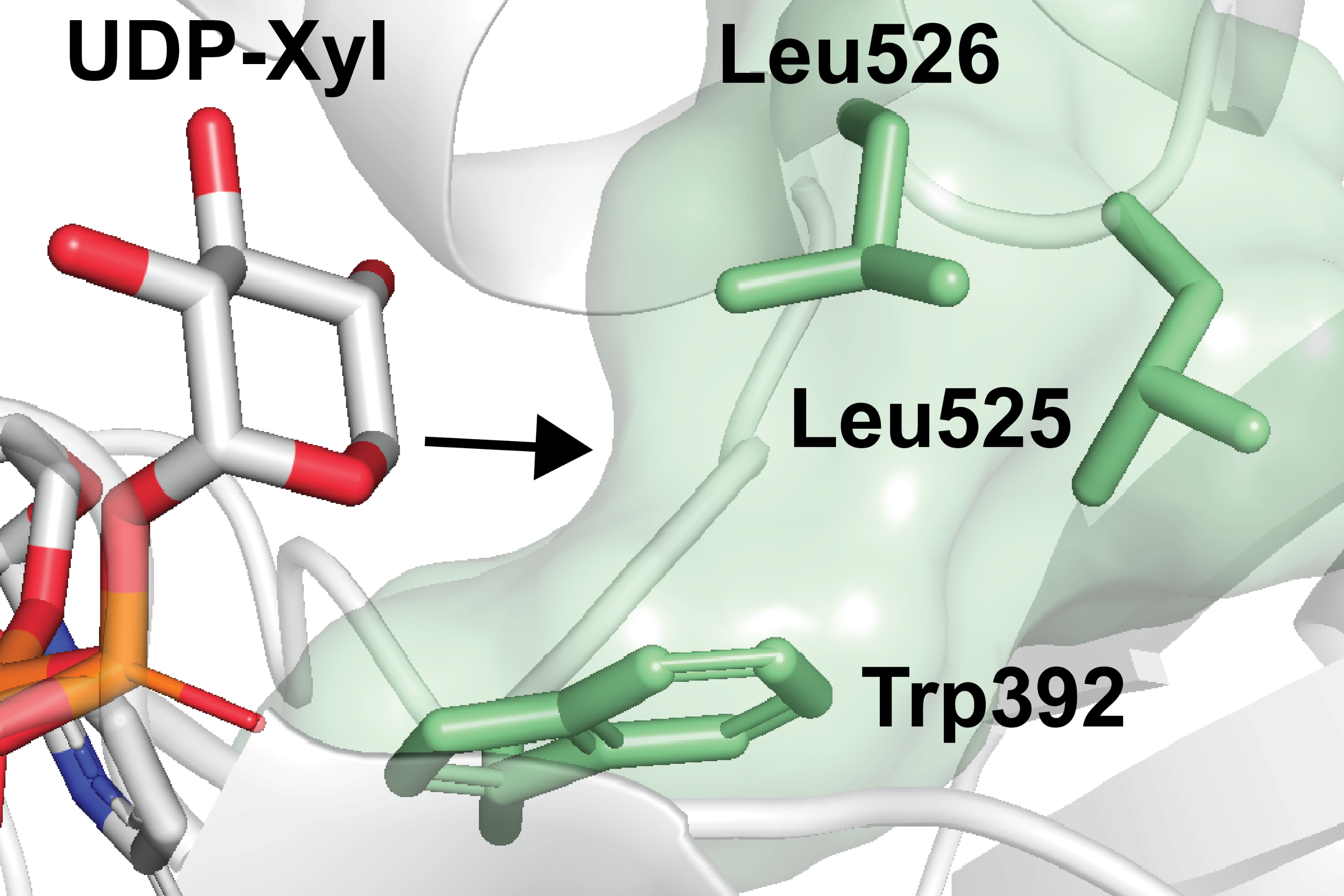

Instead of attempting to tag a whole proteoglycan, the researchers targeted a single step in its construction. Using a method called bump-and-hole engineering, they redesigned one of the enzymes that builds proteoglycans so it would attach a modified sugar containing a chemical tag.

This tag can then be “clicked” to a fluorescent marker or molecular handle, allowing scientists to see, isolate, and analyse individual proteoglycans inside living mammalian cells.

“This technique allowed us to fill in key gaps,” says Zhen Li. “The modified enzyme and sugar were successfully incorporated into normal mammalian cellular processes, showing that the technique doesn’t alter their biology.”

Opening new routes in cancer research and beyond

The ability to label and track proteoglycans in living cells could also unlock new approaches in cancer research. Tumour cells often exploit proteoglycan‑based signalling to fuel their growth, and being able to monitor, or even re‑engineer, these molecules could help researchers understand and disrupt these pathways.

Dr Schumann believes this is one of the most promising future directions: “I’m hopeful this tracking system could help us understand and even modify what signals a cancer cell is picking up, perhaps by introducing a designer proteoglycan that can’t respond to usual cancer growth drivers,” says Dr Schumann. “This might one day help us find better treatments.”

Beyond cancer, the team is excited about what the method could reveal in fundamental biology, from organ development to tissue architecture, as proteoglycans play crucial roles in shaping how tissues form and function.

Dr Schumann is now taking this chemical toolkit with him to TU Dresden University of Technology in Germany, where his lab will investigate how proteoglycans help tissues develop into complex organs.

Read the full paper here. Further information can be found on the Francis Crick Institute website.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Article people, mentions and related links

Saida Mahamed

Faculty of Natural Sciences