Scientists reveal how sleeping sickness parasites control their surface coat

by Emily Govan

Researchers have revealed how parasites hide thousands of antigens behind a single-colour coat and how disrupting this control could make the parasite more visible to the immune system.

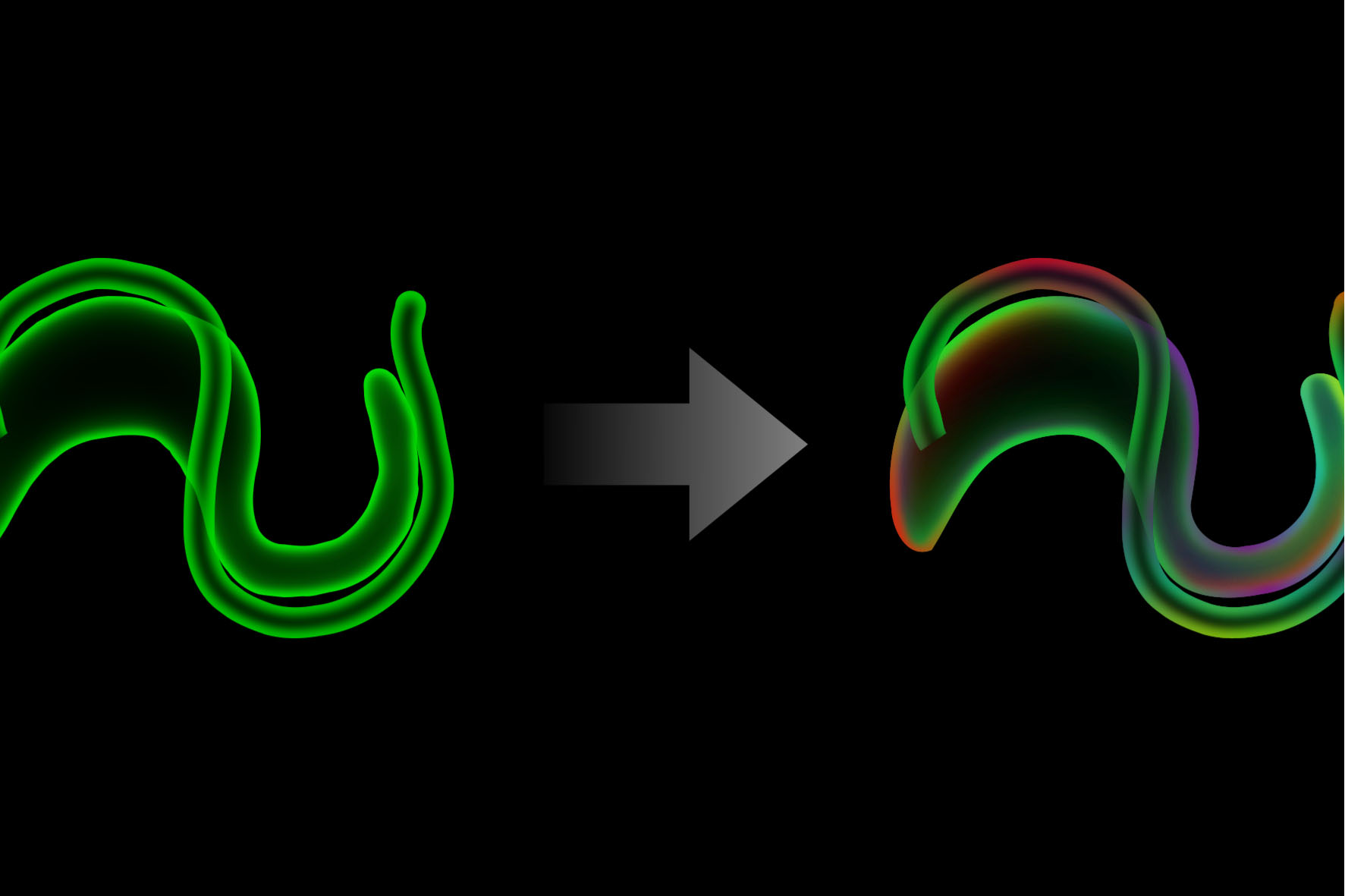

A new study from Imperial Life Sciences researchers, published in PNAS, shows how African trypanosomes survive inside their hosts by hiding behind a single-colour surface coat. Disrupting the molecular key that enforces this coat leads to expression of multiple antigens.

Single-celled parasites known as African trypanosomes cause devastating diseases in humans and livestock across sub-Saharan Africa. They express only one surface antigen at a time, effectively wearing a ‘monochrome coat’ that can be swapped for a new one whenever the host begins to detect it. The Imperial team, led by Dr Calvin Tiengwe, has now identified the molecular key behind this control. When this key, a protein called ESBX, is disrupted, the parasite can no longer restrict itself to a single antigen. Instead, it begins expressing multiple surface antigens at once.

"Trypanosomes have thousands of possible disguises but can only wear one at a time. ESBX is the factor that enforces this rule - without it, the parasite loses control and begins expressing multiple surface coat genes simultaneously." Dr Calvin Tiengwe

Dr Tiengwe said: 'Trypanosomes have thousands of possible disguises but can only wear one at a time. ESBX is the factor that enforces this rule - without it, the parasite loses control and begins expressing multiple surface coat genes simultaneously.'

One coat, thousands in reserve

The trypanosomes cover their surfaces with Variant Surface Glycoproteins (VSGs). The host immune system can recognise and destroy parasites displaying a particular VSG, but trypanosomes can switch which VSG gene is active, changing their surface coat and staying ahead of immune detection.

Although the parasite’s genome contains thousands of VSG genes, only one is expressed at a time, a phenomenon called monoallelic expression. This strict control ensures the parasite maintains its monochrome coat, essential for its long-term survival. If multiple VSGs were expressed simultaneously, the parasite would be far easier for the immune system to detect.

Previous studies showed that the single active VSG gene is transcribed in a specialised nuclear region called the expression site body (ESB). This ‘production factory’ generates large amounts of VSG from the active gene while excluding all others. Scientists had identified some proteins involved in activating the chosen VSG and others in silencing inactive genes, but how these opposing processes were coordinated remained a mystery.

Unlocking the molecular key

The Imperial team discovered ESBX, a previously uncharacterised protein that localises specifically to the expression site body in the mammalian-infective stage.

When ESBX is disrupted, the machinery controlling expression of the active VSG fails, and previously silent VSG genes start being transcribed. The parasite now expresses multiple antigen genes at once, effectively wearing a multicoloured coat that could make it more visible to the immune system.

Dr Tiengwe said: 'When ESBX is disrupted, the parasite can no longer maintain its single-colour disguise. Multiple surface antigens are expressed, which could make the parasite far easier for the immune system to detect.'

Altering ESBX levels also disrupted normal control, confirming that it is central to balancing activation of the chosen VSG with suppression of all others. ESBX acts as the molecular key linking activation of the chosen VSG with silencing of all others, maintaining the monochrome coat that allows the parasite to evade immunity.

Giving the immune system the upper hand

African trypanosomes cause sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in livestock, placing a major health and economic burden on affected regions. While this discovery does not immediately lead to new treatments, it provides crucial insight into one of the parasite’s most powerful survival strategies.

By revealing how antigen expression is tightly controlled, the work opens avenues for understanding how the system could be destabilised, potentially allowing the immune system to detect the parasite more effectively. More broadly, it helps explain how cells enforce strict ‘one-gene-at-a-time’ expression rules, a phenomenon observed across biology.

The research was conducted in collaboration with the University of Oxford, the University of Edinburgh, the University of York and Oxford Brookes University.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Article people, mentions and related links

Emily Govan

Faculty of Natural Sciences