Engineering

Imperial researchers contribute to LZ’s record-breaking hunt for dark matter and its first observation of rare neutrino interactions

Dark matter makes up 85% of the universe’s mass yet remains invisible and undetected. Understanding what it is remains one of the biggest challenges in physics, and one of the most profound questions about how our world works.

Now, the LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment has analysed the largest dataset ever collected by a dark matter detector, setting new limits on what dark matter could be and achieving a major milestone: detecting neutrinos from the Sun’s core in a way never seen before.

The paper was published earlier this week on arXiv.

Though dark matter has never been observed directly, its presence is undeniable. It acts as the invisible framework that holds galaxies together, and shapes the universe. Because it doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light, scientists cannot detect it with traditional methods. Instead, they have to find other ways to detect it.

That is where LZ comes in. The experiment is an international collaboration of 250 scientists and engineers from 37 institutions, including Imperial. Managed by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the detector operates nearly one mile underground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. This deep location shields the experiment from cosmic rays and other interference, creating the ideal environment to hunt for these rare interactions.

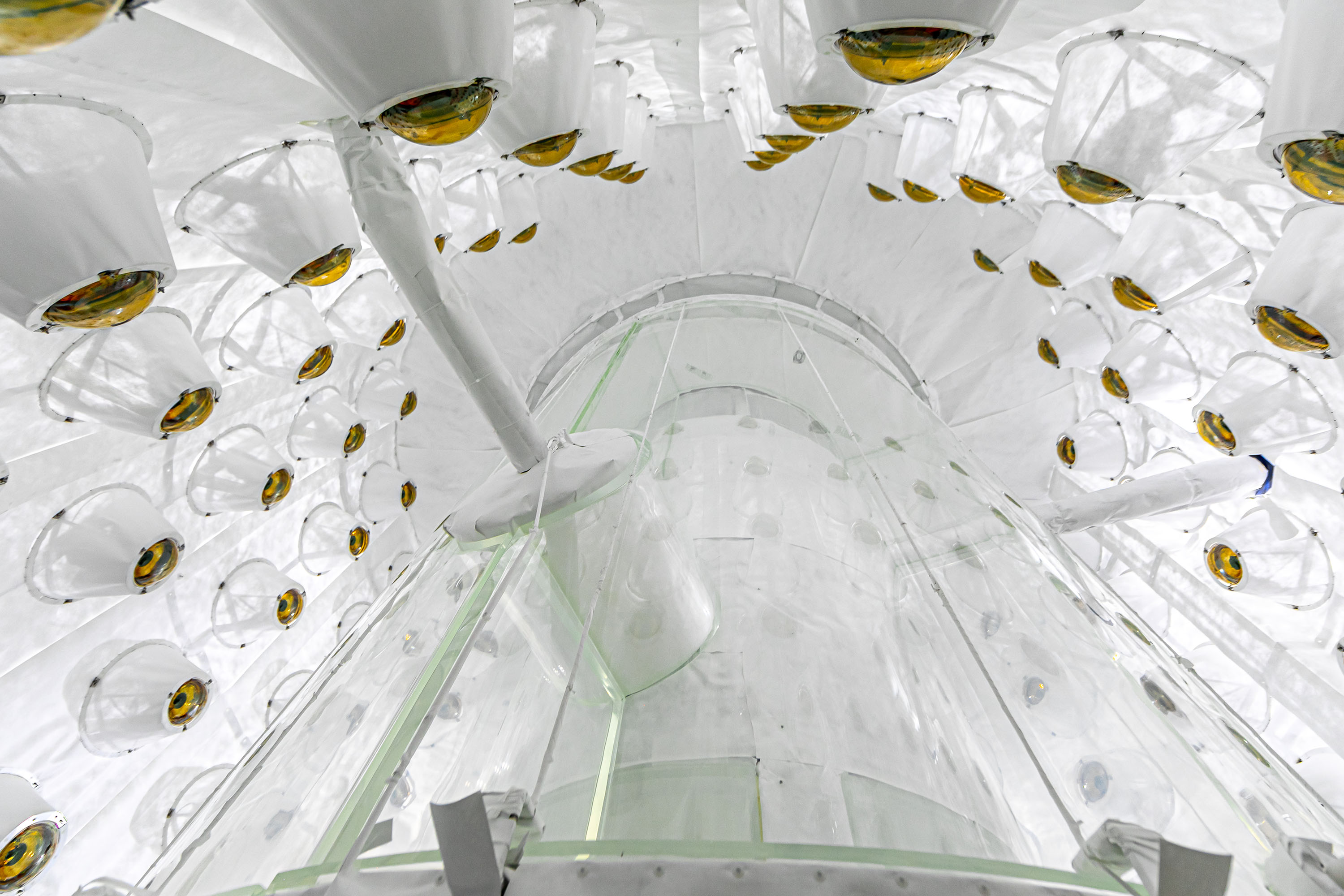

At the heart of LZ is a 10-tonne chamber filled with ultrapure, ultracold liquid xenon. If a dark matter particle – specifically a weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) – hits a xenon nucleus, it releases energy, causing the atom to recoil and emit light and electrons. Highly sensitive sensors around the chamber capture these signals, allowing scientists to reconstruct the interaction with extraordinary precision.

Thanks to advanced shielding, ultra-pure materials and precision calibration, LZ is the most sensitive dark matter detector in the world, capable of detecting the faintest signals and even explore phenomena beyond dark matter, including rare neutrino interactions.

David Woodward, deputy operations manager for LZ, said “When I step back and consider what we’ve achieved – a world-leading search for these low-mass WIMPS using the faintest signals we can see with our detector – it’s extremely rewarding and the perfect demonstration of the experiment working as it should.”

The LUX-ZEPLIN main detector in a surface lab before installation underground. Credit: Matthew Kapust/Sanford Underground Research Facility

The latest analysis, based on 417 live days of data collected between March 2023 and April 2025, found no evidence of WIMPs in the low-mass range between 3 and 9 GeV/c² (roughly three to nine times the mass of a proton). This is the first time LZ researchers have explored this lighter range, and the results set record-setting limits above 5 GeV/c², further narrowing down possibilities for what dark matter might be and how it interacts with ordinary matter.

Professor Henrique Araújo, from the Department of Physics at Imperial and lead of the UK contribution, said:

“LZ continues to operate nominally, and so we go on producing record-breaking results. This is a very complex cryogenic system, and this result shows that we built a great experiment and have a great team operating it: through underground and remote shifts, day after day, year after year.

“This lays the groundwork for a small army of skilled data analysts that look for the proverbial needle in the haystack, a few interactions hiding in several petabytes of data…, using complex machine learning tools but also a lot of hard work.”

Alongside its dark matter search, LZ achieved another milestone: detecting neutrinos from the Sun’s core. These boron-8 solar neutrinos, created by fusion in our Sun’s core, revealed new details on how neutrinos interact and the processes powering stars.

During the experiment, these neutrinos interacted in the detector through a process called coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering (CEvNS), where a neutrino interacts with an entire atomic nucleus, rather than individual protons or neutrons. Although this amplifies the probability that these neutrinos interact at all, the very low energies of CEvNS interactions make the signal extremely subtle and challenging to detect.

Hints of this interaction appeared in other detectors last year, but LZ improved the confidence level to 4.5 sigma – considered strong evidence – significantly surpassing previous experiments. This achievement not only confirms LZ’s sensitivity but also opens new opportunities to study solar physics and test the Standard Model.

Araújo added: “The data we are publishing now is a world-leading search for dark matter particles at low masses – and we unveil solid evidence for solar neutrinos interacting via the elusive CEvNS process, which is also significant.

“Personally, the solar neutrino detection is exciting to me since this confirms that we would be sensitive to neutrinos from a supernova explosion going off somewhere in our galaxy: not bad for a modest-sized dark matter detector!”

Professor Araújo leads LZUK, a team from ten UK institutions contributing to the experiment. He was a member of the LZ leadership team during the design and construction phases and co-led the development of the central Xenon Detector at the core of LZ.

Imperial also hosts one of the two data centres that stores, processes and distributes data to the collaboration. Araújo’s group includes PhD students and postdocs that have spent time in South Dakota to help build and then operate the experiment and are contributing to several LZ analyses including this one.

Linda Di Felice, an Imperial PhD student with the group said, “These new LZ results are especially exciting for me, having been on site in South Dakota during data taking. And, as LZUK Outreach Coordinator and someone passionate about sharing physics, I know how much results like these can inspire the public, and that’s wonderful to see!”

LZ will continue collecting data until 2028, aiming for over 1,000 days to probe higher-mass dark matter and explore exotic physics beyond the Standard Model – including solar axions, millicharged particles and cosmic-ray boosted dark matter.

Researchers are also planning XLZD, a next-generation experiment that will combine technologies from LZ and other projects to further expand the search for dark matter.

XLZD will be the flagship Rare Event Observatory for dark matter and neutrino physics, capable of discovering or ruling out interactions of dark matter particles over a wide range of masses. This ambitious project will culminate a highly competitive hunt that started over three decades ago.

The proposed detector will deploy a liquid xenon target around ten times larger than that of LZ, dramatically increasing sensitivity. Several underground laboratories are interested in hosting the experiment, and Professor Araújo is leading efforts to bring the experiment to the UK, where it could be housed in a major new underground facility at the Boulby mine in the North East of England.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Faculty of Natural Sciences

Engineering

Campus and community

Engineering

Engineering

Engineering

Science

Health

Discover more Imperial News

Search all articlesDiscover more Imperial News

Search all articles