Breakthrough research links dementia risk to the body clock

Words: Peter Taylor-Whiffen

Context

One in 14 of the over-65s in the UK has dementia. That’s 850,000 people – and by 2040, according to the Alzheimer’s Society, 1.5 million people of all ages will be living with this cruellest of diseases. Which is why Imperial researchers are investigating what makes someone genetically predisposed to dementia – and whether action might be taken from birth.

Background

“Alzheimer’s is a very difficult disease to track, as it develops over decades,” says Dr Marco Brancaccio, Lecturer in Dementia Research at Imperial’s Department of Brain Sciences. “But in recent years, we have discovered many chronic pathologies are connected with disruption of circadian rhythms or, as it is also called, the body clock. We wanted to establish whether there’s a link between a disruptive clock and neuro-degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.”

Methodology

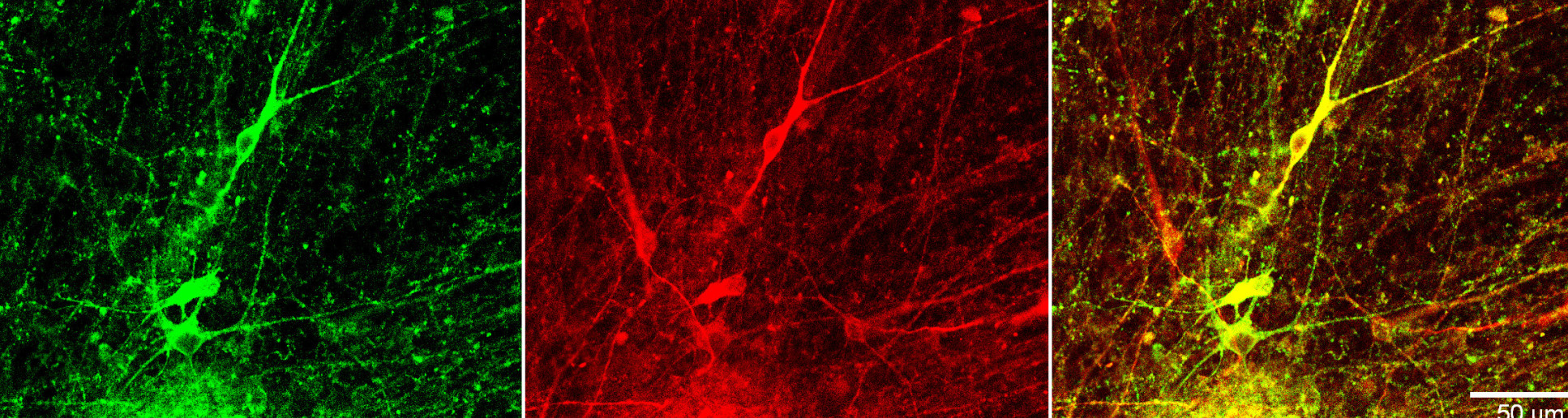

Brancaccio and his team took biopsies from healthy patients and those with dementia, working on cells in a dish that exactly mirrored the body clock of the cells still in the patient. They then used innovative stem-cell and live-imaging techniques that enabled them to track, in real time, the circadian rhythms in the removed cells. “You can’t take a brain out,” says Brancaccio, “but this model gives you a very similar molecular and cellular perspective to the actual person.” He is not aware of anyone else doing such circadian rhythm research on cells from Alzheimer’s patients.

Findings

“We went in with an open mind but were surprised and excited to discover the speed of the clock was different – slower – in those patients with dementia,” says Brancaccio. “By isolating the cells from the patient, we reversed them back into an embryonic-like stem cell. That ‘wipes them clean’, as if the patient had just been born, with no memory of the disease. Because they have become brand new cells with no memory and no effects of ageing, if they then still display disruptive circadian rhythms, that might suggest there are genetic features connected to the body clock that make those cells more at risk of developing the disease.”

Outcomes

The excitement is not just the possibility of detecting a link, says Brancaccio, it’s the potential that it might be preventable. “We want to understand the genetic mechanism behind the disruption of the clock, because there are no obvious reasons why this should be the case. Once we do, the next challenge is to see if we can interfere with those genes and, much further down the line, design drugs that counteract these effects. This is a marker – in principle we could use this as a way to infer people’s risk of developing the disease. It’s still a little bit of chicken and egg – is the disruption of your clock, which you can identify at birth, indicating you’re more at risk, or is the clock one of the very first mechanisms impacted by the initiation of Alzheimer’s? We still need to answer that question. What we do know now is that if you have a weaker body clock, there is an exponentially greater risk of developing dementia, so there must be something there.”

Professor Marco Brancaccio is a lecturer in Dementia Research and UK Dementia Research Institute Fellow.