High energy density physics (HEDP) is the subject of how matter and radiation behave at temperatures in excess of a million degrees C°, and densities from that of liquid water (1 gram per cubic centimetre) to many times the density of solid lead. A more technical definition is any volume with an equivalent energy density of 1011 J/m3 or more, or a pressure of 1 Mbar and above.

At these densities and energies, matter becomes plasma, also known as the fourth state of matter (the other three being solids, liquids, and gases). Plasmas are very different to the other states of matter, and support an extremely rich variety of complex physical phenomena, which makes them compelling to study. HEDP includes the study of fusion plasmas, high intensity lasers, stellar interiors, early universe plasmas, and supernovae.

High energy density physics is the focus of the work of Professor Steven Rose, but many other members of the Plasma Physics Group also work on HEDP. Examples of Professor Rose’s research interests are listed in more detail below.

High Energy Density Physics

- Inertial confinement fusion

- Muon catalysed fusion

- Line coincidence photopumping

- Matter from Light

- Radiative opacity

- Line radiation transport and geometry

- Electrostatic shock heating of ions

- Photoionised plasmas

- Relativistic electron distributions

Several members of the Plasma Physics Group at Imperial College work on Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF) through the Centre for Inertial Fusion Sciences (CIFS) and we have strong links with Lawrence Livermore’s National Ignition Facility (NIF) in California, where the world's largest inertial confinement fusion experiment is based and where fusion energy gain was achieved for the first time.

We are working on developing methods of target design optimization using machine learning , on the symmetry of point source irradiation of a fusion capsule, on using accelerated D and T ions to produce a fusion afterburner and on using the output from a burning ICF plasma to probe aspects of fundamental science from particle physics through astrophysics to cosmology.

One of the most speculative potential uses of the output from a burning ICF plasma involves theoretical work which has provided formulae for the rate of electron-positron pair production. This work predicts that by coupling the radiation from a burning plasma with a strong electric field produced by counter-propagating ultra-high intensity lasers the electron-positron pair production rate (called the thermal-Schwinger effect) will be vastly higher than that produced by either the radiation field or the electric field alone. The new expression is a rare example of an all-orders and all-loop result in QED and an experimental validation would have implications for strongly-coupled physics and conjectured all-order behaviours in QED that have relevance to the search for magnetic monopoles.

The two most common approaches to fusion energy, magnetic and inertial confinement fusion, overpower the Coulomb repulsion using very high temperatures. Muon catalyzed fusion, on the other hand, uses the strength of the bond of a diatomic molecule to get the nuclei within the required range.

Negative muons are leptons that are about 200 times heavier than electrons with a lifetime of 2.2 microseconds. They are introduced to a mixture of deuterium (D) and tritium (T) and quickly become the binding particle in muonic DT molecules. The internuclear distance is inversely proportional to the mass of the binding particle so is reduced by a factor of 200 allowing the fusion reaction D + T -> n + α to occur where n is a neutron and α is an alpha particle (i.e. a helium-4 nucleus). Between them, the n and α have 17.6 MeV of kinetic energy. This energy is used to boil water, turn turbines and create electricity.

Usually, the negative muon is simply released to form another DT molecule and catalyze a subsequent fusion reaction. However, in about one out of every 200 reactions, the muon sticks (and remains stuck) to the positively charged alpha particle. This “alpha sticking”, in combination with the finite lifetime of the muon, limits the number of reactions catalyzed by a single muon to be about 150 on average.

The viability of using muon catalyzed fusion to produce commercially viable power depends on the number of fusion reactions catalyzed per muon and the energy cost of producing each muon. It is estimated that, with current technology, the amount of electricity produced by a muon catalyzed fusion reactor would be equal to 14% of the electricity consumed.

We are primarily focused on exploring ways of minimizing the costs of muon production. It is believed that this process can be improved significantly which would bring this elegant method of producing fusion reactions closer to being a useful method of producing electricity.

Experiments have been performed over a number of years that attempt to tailor the radiation field in a laser-produced plasma and thereby influence, by direct photopumping, the excitation and ionisation. A mechanism often considered is line coincidence photopumping, in which a strong, narrow-band source of X-rays produced by line radiation from one plasma is used to pump directly a resonant transition in a physically separate plasma.

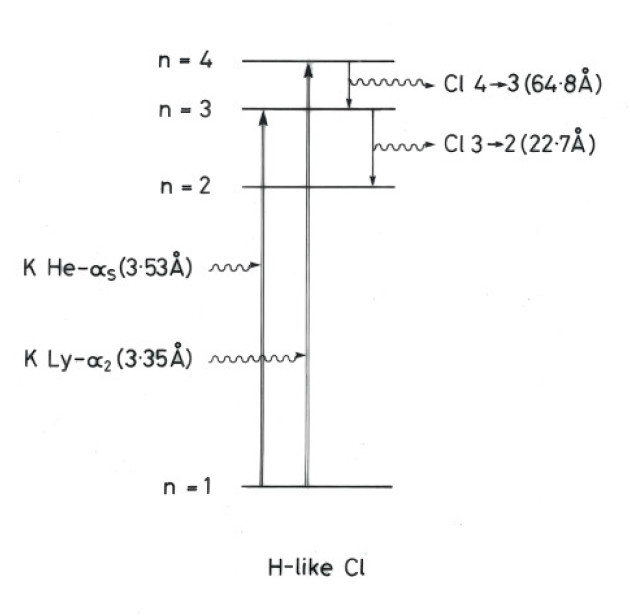

We have modelled experiments on the ORION laser at AWE that have shown line-coincidence photopumping of H-like Cl by H- and He-like K ions in the same plasma for the first time. The experiments have shown a population enhancement in upper levels of H-like Cl which was diagnosed by enhancement of spectral line intensity of the n=4-3 transition in the H-like Cl ions. The experimental analysis employed both real (KCl) and null (NaCl) shots. The technique of bootstrapping was employed that allowed several different real and null experimental shots to be combined in a statistically meaningful way and resulted in a probability distribution for the enhancement.

The experiments are relevant to astrophysical plasmas in which we have shown that line-coincidence photopumping operates in flares on the Sun. In both cases the line-coincidence is between He-like Na which pumps He-like Ne; with both ions present in the same plasma. These observations represent the first time such pumping has been observed to operate in an astrophysical plasma in the X-ray range.

Figure shows the KCl line-coincidence pumping scheme. Enhancement was seen on the 64.8Å line.

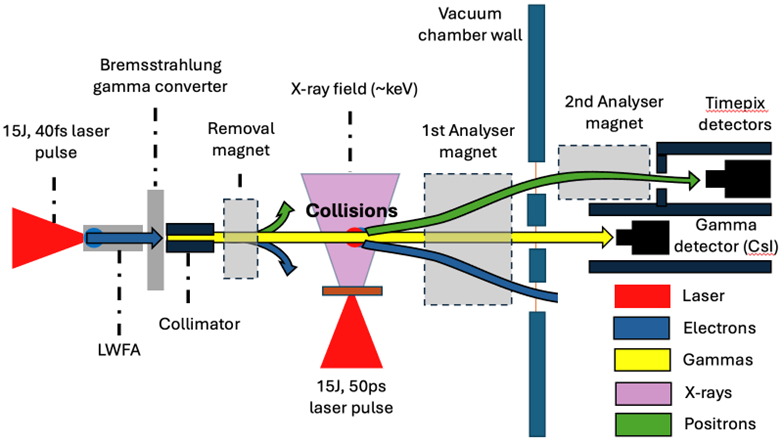

As the inverse of Dirac annihilation, the Breit-Wheeler process, the production of an electron-positron pair in the collision of two photons, is the simplest mechanism by which light can be transformed into matter. However, in the 90 years since its theoretical prediction, this process has never been observed. In 2014 we published a paper showing how that might be done using high-power laser facilities. The first experimental campaign was undertaken in 2018 together with simulations of the experiment which included the Breit-Wheeler cross-section into a model of the experiment using the code Geant4. An intense gamma-ray beam, generated through the bremsstrahlung emission of wakefield accelerated electrons passing through a solid bismuth target, was fired into an X-ray radiation field generated by irradiation of a Ge coated plastic foil. Extraneous electrons and positrons emerging from the back surface of the bismuth were deflected using a magnetic field, to prevent them interacting with the X-ray field. The muliti-picosecond duration and millimetre size of the X-ray field makes spatio-temporal overlap of the gamma and X-ray sources straightforward. Any Breit-Wheeler produced pairs were emitted in a narrow cone, due to the Lorentz boost. By using a second magnetic field individual positrons produced through the Breit-Wheeler process were separated from the electrons and detected. The positron detection took place by both Timepix and CsI detectors. The gamma beam was diagnosed using a separate CsI detector and the X-ray field was diagnosed using absolutely calibrated crystal spectrometers.

Schematic diagram of the 2018 experiment

A feature of the experiment was that a roughly equal number of shots were taken where the second, X-ray generation laser beam was fired to those in which it was not fired. This allowed a comparison between shots in which we potentially could have seen positrons from the two-photon pair creation process (‘full shots’) and shots in which that was impossible because the second of those photons (the X-ray photon) wasn’t present (‘null shots’). A comparison between ‘full’ and ‘null’ shots which were otherwise nominally identical allows a way to remove from the analysis any positrons or other background created by means other than the two-photon pair creation process. Analysis of the data from the 2018 experiment showed that for an unambiguous demonstration that matter has been made from light a new experiment incorporating improvements to all aspects of the complex setup is needed and that is scheduled for the first half of 2026.

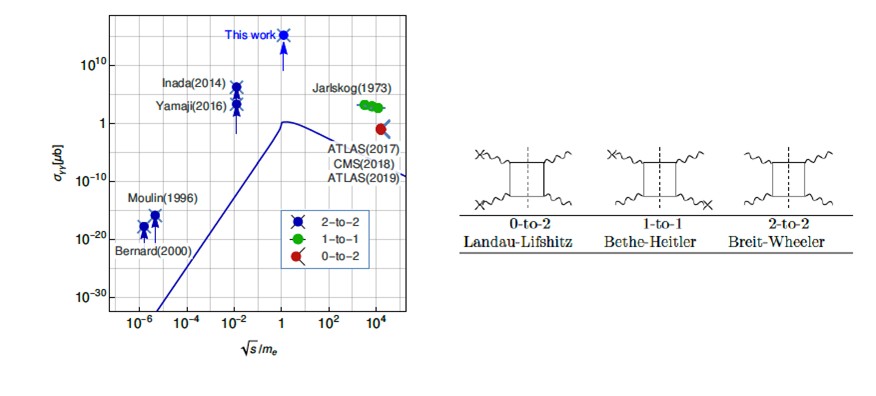

Whilst we have not published data on pair production from the 2018 experiment, we have published an analysis of the potential scattering of the gamma photons as they transit the X-ray field. Through statistical analysis we determined that there was no evidence of such scattering which led to us to determine a new upper bound in the photon-photon scattering cross-section for photons in the centre of momentum energy of order 1 MeV. This is a range that has not been explored in previous experiments using optical lasers or ultraperipheral heavy ion collisions, yet is of particular interest in astrophysics. Whilst the 2018 experiment placed a bound at 1015 σQED (104 lower than previous bounds at low energy), the improvements to the experimental setup in the 2026 experiment will further reduce this by a factor of 102-3. This in turn will lead to more stringent bounds on Non-Standard Physics models.

Current bounds on the photon-photon scattering cross-section taken from our recent paper

The radiative opacity of a plasma influences its evolution when radiation transport is important. Indirect-drive inertial confinement fusion is particularly dependent on accurate knowledge of the opacity of both the hohlraum and ablator material. The structure and evolution of the Sun is critically influenced by the opacity of the solar plasma. The opacity is determined by the electronic structure of the plasma and it is the interaction between the photons in the radiation field and the bound and free electrons that determine the opacity.

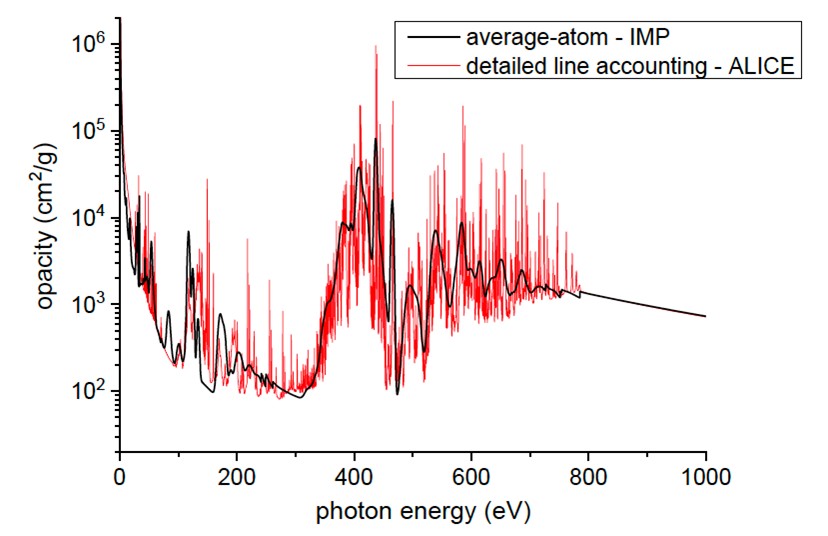

We have developed models of radiative opacity employing different levels of approximation from detailed configuration accounting to detailed term accounting and incorporating new models of line-broadening using second-order electron-photon and two-photon descriptions.

The LTE opacity of Chlorine at 100eV and 0.001g/cc calculated using detailed configuration accounting (black line) and detailed term accounting (red line).

Testing those models in experiments using high-power lasers has been undertaken using absorption spectroscopy (where long-pulse, nanosecond, beams are employed) and emission spectroscopy (where short-pulse, picosecond, beams are used).

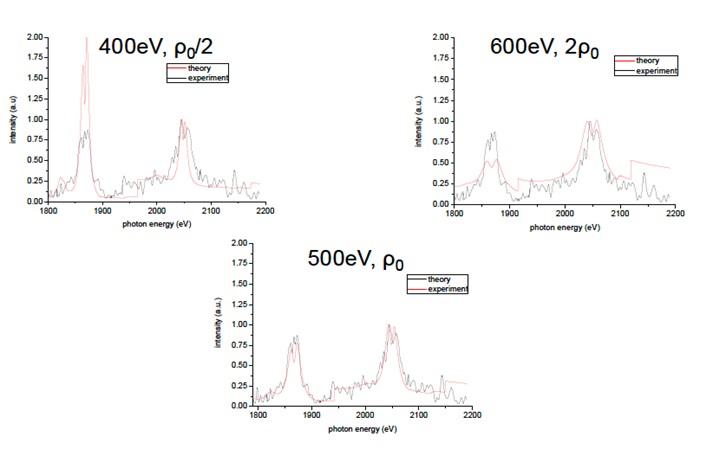

Fitting the intensities and widths of Al Lyman-β and Helium-β lines using the code ALICE determines the temperature and density (ρ0 is solid density) in the opacity experiment.

A series of plasma absorption opacity experiments over the last 15 years by a group at Sandia National Laboratory has shown a consistent discrepancy with opacity models of iron under conditions similar to those found at the radiation / convection boundary in the Sun. Other laboratories have attempted to reproduce the Sandia results using similar absorption spectroscopy techniques. However a new method of determining the opacity using a measurement of the speed of propagation of a supersonic radiation wave has (based on earlier theoretical work) was recently undertaken at the National Ignition Facility. This work shows no such discrepancy with current opacity models which has significant implications for solar modelling where, recently, solar opacity models have been adjusted to agree with the Sandia experimental data. This paper throws those adjustments into doubt.

The calculation of LTE opacity assumes that the excitation and ionization is determined entirely by statistical mechanics. Whilst this is a good approximation in the interior of stars, the excitation and ionization is often not in LTE, particularly for plasmas which are optically thin over most of the radiation field spectrum. In this case modelling needs, in general to solve the rate equations for the populations of ions in the plasma together with the radiation field. In the case where only a few strong lines are optically thick (which is a situation often encountered in both laboratory and astrophysical plasmas) the spectrum, particularly line ratios and line widths are often used to provide valuable diagnostics of the temperature and density in the plasma. We have developed a new diagnostic that relates the ratio of intensities in spectral lines to the geometry of the emitting plasma. The physics of this effect comes from the mean chord in the plasma, which determines the escape factor of a line, being dependent on the shape of the plasma. This has been used in spectra from both the Sun and stars and has the potential to give information on the geometry of a remote plasma that cannot be spatially resolved. We have demonstrated the same effect in the laboratory in recent plasma experiments on the Omega laser.

In a recent paper we have shown that ion-ion collisions driven by short-pulse laser-plasma interaction can produce the fastest macroscopic ion heating in the laboratory (ion collisions in particle accelerators such as the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider produce much faster heating but this is at the microscopic scale of the nucleus). The process involves a strong electrostatic shock in a plasma which involves two differing ion masses. The electrostatic field in the wave accelerates the two species differently which then collide with one another and the ions are heated. We calculate that for a CsH plasma the ions are heated at the rate of over 107K/10-14sec. This is faster than the rate of heating of the ions in a burning DT plasma. This rate is equivalent to changing the temperature from cold to that found in the middle of the Sun in a time that is shorter than that taken for light to travel the width of a human hair.

Photoionised plasmas are found in a variety of astrophysical situations where the ambient broadband radiation field is sufficiently high and the electron number density is sufficiently low that photoionization and photoexcitation dominate over electron collisional ionization and excitation. This situation is not usually found in laboratory plasmas where collisional processes dominate although over the last few years there have been a number of attempts to produce such plasmas in the laboratory, and we have been involved in the design and analysis of some of those. In astrophysics photoionized plasmas are characterized by the photoionization parameter

ζ=4πF/ne

where F is the radiative flux and ne is the electron number density. ζ is usually expressed in units of ergcms-1. A low-mass X-ray binary has a typical photoionization parameter of 30ergcms-1 whereas a Seyfert galaxy has a typical value of 1000ergcms-1. In the astrophysical case the radiation field is supplied by emission from an accretion disk which forms around a compact object. The analysis of the spectra from such objects (usually in the X-ray range taken on satellites such a XMM and CHANDRA) can tell us about their structure and behaviour but this requires models of excitation and ionization that account for all the processes taking place in the photoionized plasma. One well-used model is CLOUDY and we have been involved in experiments to validate CLOUDY (and other photoionization codes) against laboratory experiments.

Artist impression of EXO 0748-676, a low-mass X-ray binary, ζ=30 ergcms-1

Artist impression of NGC 4593, a Seyfert galaxy, ζ=300 ergcms-1

We have used photoionized plasmas produced using pulsed power devices and high-power lasers and have initially achieved photoionization parameter of 20-25ergcms-1. To get to a higher photoionization parameter we proposed a method that does not use a broadband radiation source but rather uses a narrower source which only drives certain rates but still allows a comparison between modelling and experiment. There is still a long way to go before we can produce a plasma in the laboratory that is a full analogue of the astrophysical case; we still need to address differences between the two plasmas such as the laboratory plasma typically evolving in time whereas the astrophysical plasma is in a steady-state.

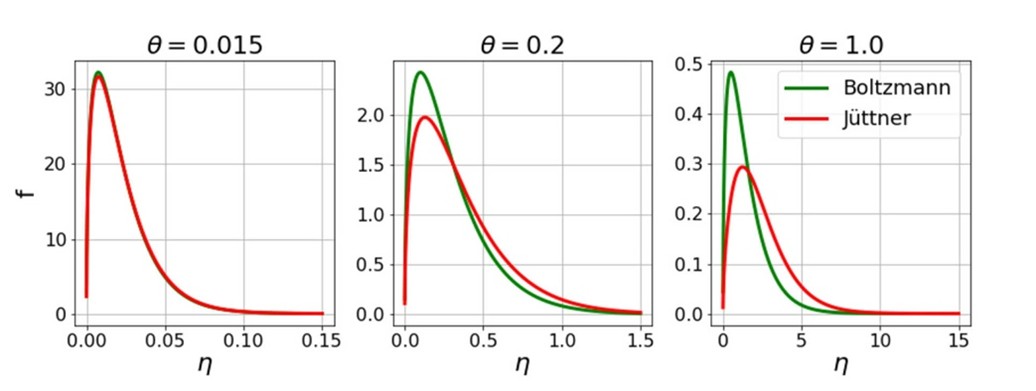

The Boltzmann energy distribution of energies of free particles in thermodynamic equilibrium is a low-temperature limit of the more general Maxwell-Juttner distribution that properly accounts for particles in the distribution having velocities close to the speed of light. For laboratory plasmas this difference is only potentially seen for electrons. We have calculated the effect on various plasma properties of using a Maxwell-Juttner rather than a Boltzmann distribution, including the effect on electron excitation and ionization rates and on the transport properties of plasmas.

Maxwell–Boltzmann and Maxwell–Jüttner distributions plotted against reduced kinetic energy (η = ε/kT - where ε is the electron kinetic energy), for a range of temperatures θ = kT/mc2