Scientists devise way to track space junk as it falls to Earth

by Simon Levey

Researchers have devised a new and quicker way to track falling space debris, using existing networks of earthquake-detecting seismometers.

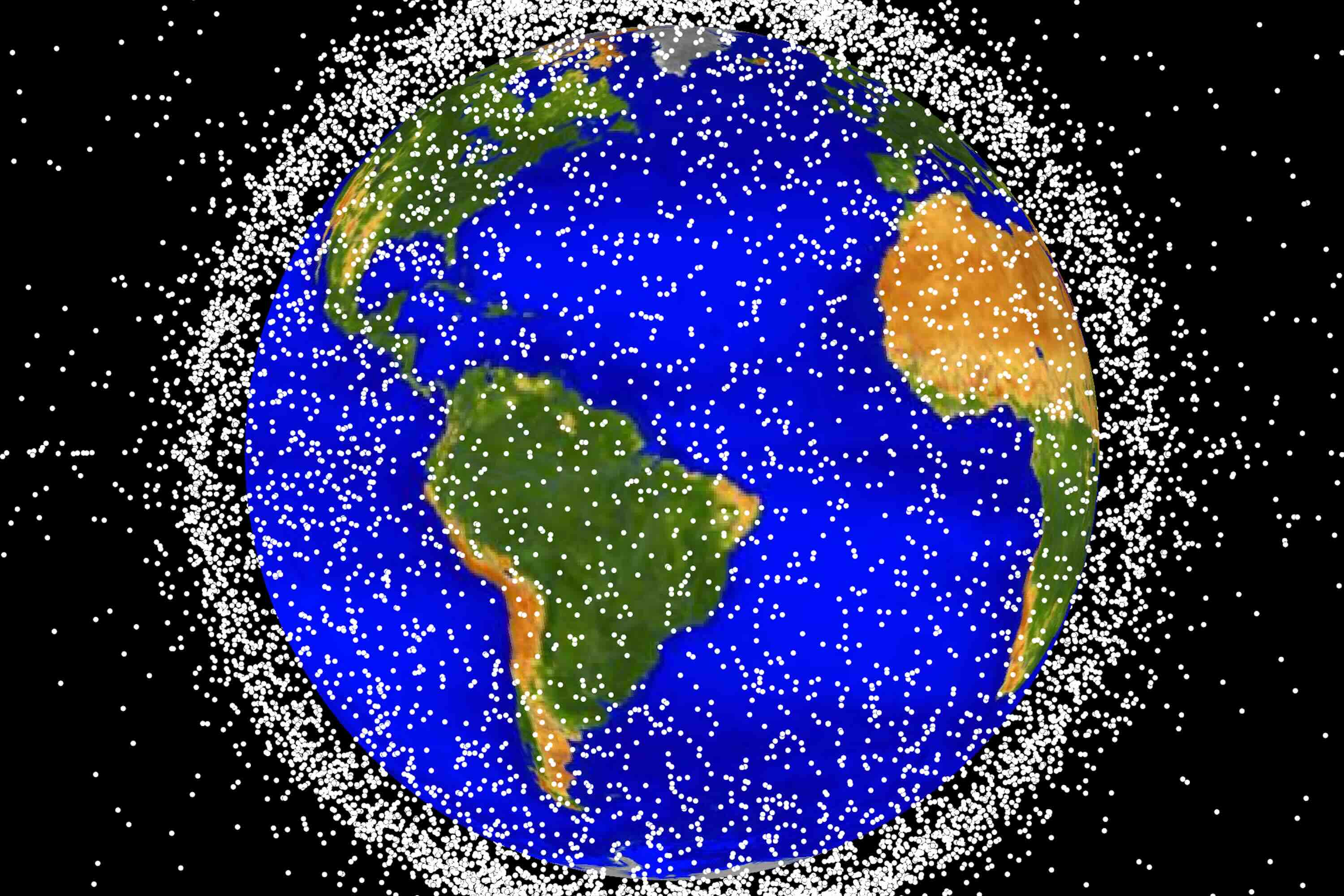

Space debris are thousands of pieces of human-made objects abandoned in Earth’s orbit and they pose a risk to humans when they fall to the ground.

The new tracking method generates more detailed information in near real-time than authorities have today—information that should help to quickly locate and retrieve the charred and sometimes toxic remains. The findings, by two researchers from Imperial College London and Johns Hopkins University, are published today in the journal Science.

“Decaying space junk is a growing problem, not just clogging up Earth’s orbit, but causing disruption when objects break up over busy or populated regions. For example, in 2025 a SpaceX Starship test flight disintegrated, and debris fell over parts of the Caribbean, prompting temporary air-traffic restrictions and aeroplanes to be grounded,” said Dr Constantinos Charalambous, co-author of the new study from Imperial’s Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering.

Engulfed in flames, falling debris sometimes produces toxic particulates that can linger in the atmosphere for hours and waft to new parts of the planet as weather patterns change. Knowing the trajectory of the debris will help organizations track where those particulates go and who might be at risk of exposure.

Dr Charalambous and co-author Dr Benjamin Fernando, a postdoctoral research fellow at Johns Hopkins University, and alumnus in Physics from Imperial College London, used seismometer data to reconstruct the path of debris from China’s Shenzhou-15 spacecraft after the orbital module entered the Earth’s atmosphere on April 2, 2024. Measuring roughly 7 feet across and more than 1.5 tons, the module was large enough to potentially pose a threat to people, the researchers said.

Space debris entering the Earth’s atmosphere moves faster than the speed of sound and, consequently, produces sonic booms, or shock waves, similar to those produced by fighter jets. As the debris streaks toward the Earth, vibrations from the shockwave trail behind, rumbling the ground and pinging seismometers along the way. Mapping out the activated seismometers allows researchers to follow the debris’ trajectory, determine which direction it’s moving, and estimate where it may have landed.

By analyzing data from 125 seismometers in southern California, the researchers calculated the path and speed of the module. Cruising at Mach 25-30, the module streaked through the atmosphere traveling northeast over Santa Barbara and Las Vegas at roughly 10 times the speed of the fastest jet in the world.

The researchers used the intensity of the seismic readings to calculate the module’s altitude and pinpoint how it broke into fragments. Then, they used trajectory, speed, and altitude calculations to estimate the module was traveling approximately 25 miles south of the trajectory predicted by U.S. Space Command based on measurements of its orbit.

“The most critical part of an uncontrolled re-entry to understand is the brief ‘chaotic disintegration’ phase, when the spacecraft breaks up. It can be hard to quickly pin down the area where any surviving debris could crash. This is especially important over places where people live or aircraft are flying,” Dr Charalambous said.

It can be hard to quickly pin down the area where any surviving debris could crash. This is especially important over places where people live or aircraft are flying.” Dr Constantinos Charalambous Study author

Near-real time tracking will also help authorities quickly retrieve objects that make it to the ground, the researchers said. Such rapid retrievals are especially important because debris can carry harmful substances.

“In 1996, debris from the Russian Mars 96 spacecraft fell out of orbit. People thought it burned up, and its radioactive power source landed intact in the ocean. People tried to track it at the time, but its location was never confirmed,” Dr Fernando said. “More recently, a group of scientists found artificial plutonium in a glacier in Chile that they believe is evidence the power source burst open during the descent and contaminated the area. We’d benefit from having additional tracking tools, especially for those rare occasions when debris has radioactive material.”

Previously, scientists had to rely on radar data to follow an object decaying in low Earth orbit and predict where it would enter the atmosphere. The trouble, the researchers said, is that re-entry predictions can be off by thousands of miles in the worst cases. Seismic data can complement radar data by tracking an object after it enters the atmosphere, providing a measurement of the actual trajectory.

“My lab at Imperial normally studies Marsquakes and the hidden interior of the red planet, where we pull big insights from very subtle vibrations,” Dr Charalambous explained. “With this study, we applied the same core idea on earth; using existing seismic networks to ‘listen’ for vibrations on the ground that occur following the sonic boom created by a spacecraft re-entering the atmosphere.

“What’s exciting is that by analysing those ground vibrations across a network of seismic detectors, we can determine the path of descent and see how the breakup unfolds rapidly as the signals come in. This vital information can help air traffic control and civil emergency services narrow down the area at risk where surviving chunks of spacecraft could land. It’s important those decisions are based on evidence, not guesswork.”

“If you want to help, it matters whether you figure out where it has fallen quickly—in 100 seconds rather than 100 days, for example,” Dr Fernando said. “It’s important that we develop as many methodologies for tracking and characterizing space debris as possible.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Article people, mentions and related links

Simon Levey

Administration/Non-faculty departments

- Tel: +44 (0)20 7594 5650

- Email: s.levey@imperial.ac.uk

- Articles by this author