Why does investment spark more violence?

Words: Helena Pozniak

Context:

Over a beer with friends fresh back from Afghanistan, economist Tamar Gomez (MRes Imperial College Business School 2016) heard something that made her do a double-take. “They told me that when winter came and snow caused roads to be closed, Kabul became a less violent place.” Gomez – who served in the Middle East as a reservist with the French armed forces – was intrigued. “Why should a lack of a good road network coincide with less violence? Shouldn’t an investment in that network help limit unrest, rather than the opposite?”

Background:

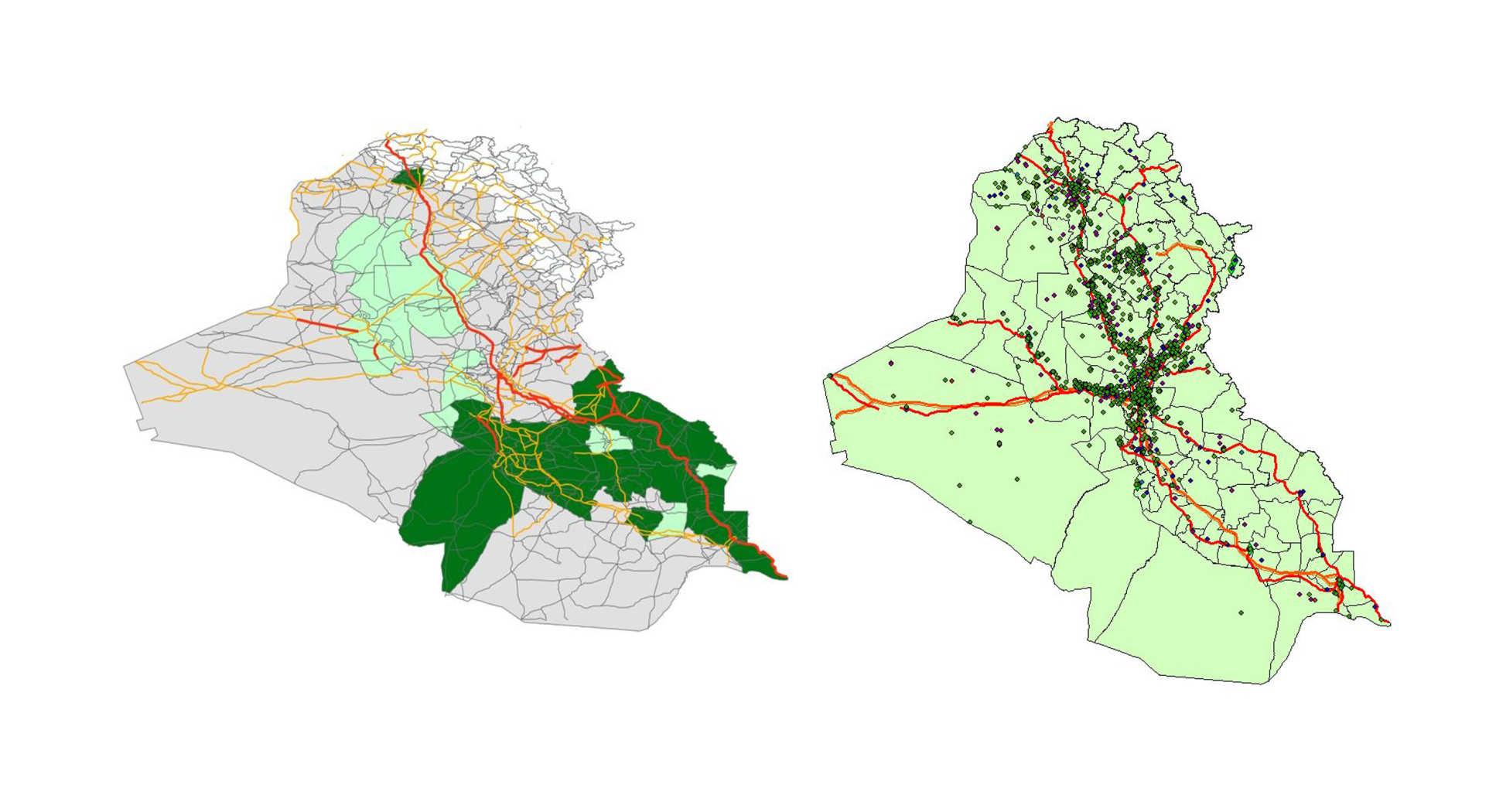

Data is hard to come by in Afghanistan, but in neighbouring Iraq, violence is well documented by the US military and NGOs – and so that was where Gomez decided to focus. In the years following the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, the United States pumped around $11.9bn into the Iraqi road network, which expanded by 21 per cent. But violence soared and, at its peak, more than 1,500 civilians were killed every month.

Methodology:

It took nearly a year for Gomez to amass the granular information that would enable rigorous statistical analysis. She analysed how much US and aid agency money was invested in roads and infrastructure, and doggedly tracked down individuals working for NGOs in Iraq and government officials to interview. Then she compared records from Iraqi NGOs and information collated by the US-hosted Global Terrorism Database, looking at population density and economic activity, in order to plot trends in violence and eliminate inaccuracies.

Findings:

What Gomez discovered was completely at odds with the US doctrine that investment in infrastructure brought greater stability. Far from bringing peace and prosperity, building roads actually sparked greater levels of violence in Iraq. “We’ve proved this is a cause rather than a correlation,” she says. But why is this the case? Gomez speculates that roads may allow violence to spill from one area to another more easily, or that the roads themselves become targets, especially when they are built by occupying forces. Harder to prove is the theory that cash investment increases levels of corruption, which could have a knock-on effect on sectarian violence.

Outcomes:

Since her discovery, Gomez’s work has been picked up by The Economist, she has presented her findings to a European conference and been asked to address an international policy think tank in Washington. She is now working on a second Iraqi paper looking at the links between aid, corruption and development. “I believe there needs to be more research around investment in infrastructure in nations where there is a military presence – there’s huge potential, for instance, to investigate within Syria.”

Tamar Gomez is a research postgraduate whose work focuses on development economics, game theory and conflicts.